The Illuminating History of Walter Burton, America’s First Black Sheriff

Walter Moses Burton was born into slavery, but eventually served four terms in the Texas state senate during the progressive but brief Reconstruction period. Visiting his gravesite in Richmond, Texas, offers an important glimpse into Texas’—and the South’s—political history.

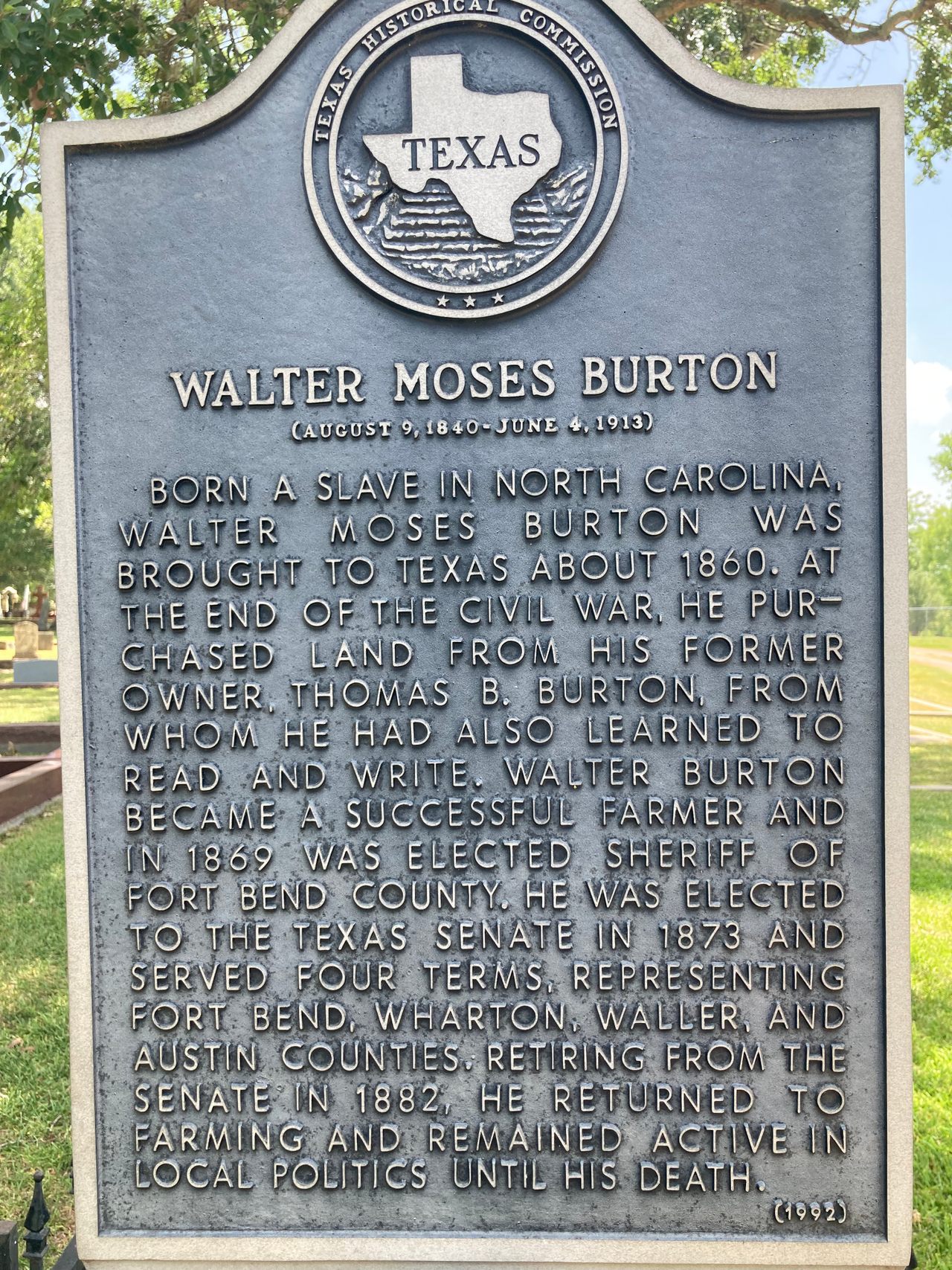

At the quiet Morton Cemetery in Richmond, Texas, a historical marker set up on a pole announces itself in front of a small, grey tombstone. The headstone, enclosed by black metal fence, belongs to Walter Moses Burton, America’s first Black sheriff.

Burton was born into slavery in North Carolina, though the exact year of his birth is disputed. His gravestone claims his birth year as 1840, while the Texas State Historical Association’s biography of Burton states he was born in 1829. As a young man, Burton was taught to read and write by his enslaver Thomas Burton, who owned plantations and had agricultural interests in Fort Bend County. Those reading and writing skills proved indispensable later in life.

“He taught him how to read and write so he had skills in his back pocket at a time when it was illegal to teach Black people those things,” explains Ana Alicia Acosta, site manager at Fort Bend Museum. “I think for [Walter], that really transformed what he wanted to do. He understood just how important education was for African Americans.”

After Walter’s emancipation, Thomas Burton sold him a sizable chunk of farmland for approximately $1,900, making Walter one of the wealthiest landowners in Fort Bend County in the onset of Texas’ short-lived Reconstruction era.

In 1866, African Americans were granted the right to vote and run for office for the first time in U.S. history, ultimately fostering the rise of a Black political class across the Deep South. In 1869, Burton, who ran as a Republican, was also elected sheriff and tax collector of Fort Bend County. Not only was he the country’s first Black sheriff, he was the county’s first Black officeholder. He served the role for four years. Some historians believe Burton may not have been allowed to arrest white citizens at the time, instead consigning a white deputy to the task.

Between 1874 and 1882, Burton served four terms in the Texas state senate. “Reconstruction is really an anomalous time in Southern history where Black and white people do come together and form these Reconstruction governments for years and really their greatest legacy is public education, across the South, and Texas,” says Matthew Clavin, a history professor at the University of Houston.

While Burton was an anomaly in many respects, he along with other post-slavery trailblazers such as Matthew Gaines and George Ruby comprised a group of at least 52 Black men who served as Texas legislators during the Reconstruction era following the Civil War. At the time, aspiring Black politicians only ran on a Republican ticket; Democrats were then vehemently opposed to emancipation.

“You have these multiple variables coalescing that absolutely foster the rise of a Black political class, just months and years after emancipation.” Clavin says. “From sheriff’s offices, and postmaster’s offices, all the way up to the United States Senate, you have Black politicians emerge across the South, and it’s really an extraordinary moment.”

As a state senator, Burton advocated for sensible gun control, fought against the state’s convict leasing system, and also championed Black education.

“He was a conservative senator interested in the education of African Americans,” says Merline Pitre, a professor of history at Texas Southern University. “He walked a straight line. He was a senator who didn’t rock the boat, but one who stood up for African Americans, particularly in the field of education.”

In 1876, Burton, along with another influential Black legislator of the period, William H. Holland, helped to pass a bill that facilitated the founding of Prairie View Normal School, which today is known as Prairie View A&M University. “They were interested in education, anything that would allow African Americans to become educated because that was the means of mobility in this country,” Pitre adds.

In the state senate, Burton earned the respect of his Black colleagues and white Republicans alike—so much so that he was gifted with an ebony and gold cane by his fellow lawmakers. He also had a reputation for being one of the more debonair figures in the state capitol at the time.

“He was the best-dressed politician in office and that was speaking across the board, white or Black: he was the best dressed,” says Acosta.

Burton stayed active in local and state politics until his death in 1913. It would take another 90 years—and Barbara Jordan’s electoral win in 1966—before another person of color was elected to the Texas state senate.

“People think that today we are at our most democratic point,” Clavin adds. “During the early years of Reconstruction, America reached its apex, if you will, of interracial government and interracial democracy, and we’ve retreated from that. We’re slowly getting back to trying to replicate that, but I don’t think we have yet.”

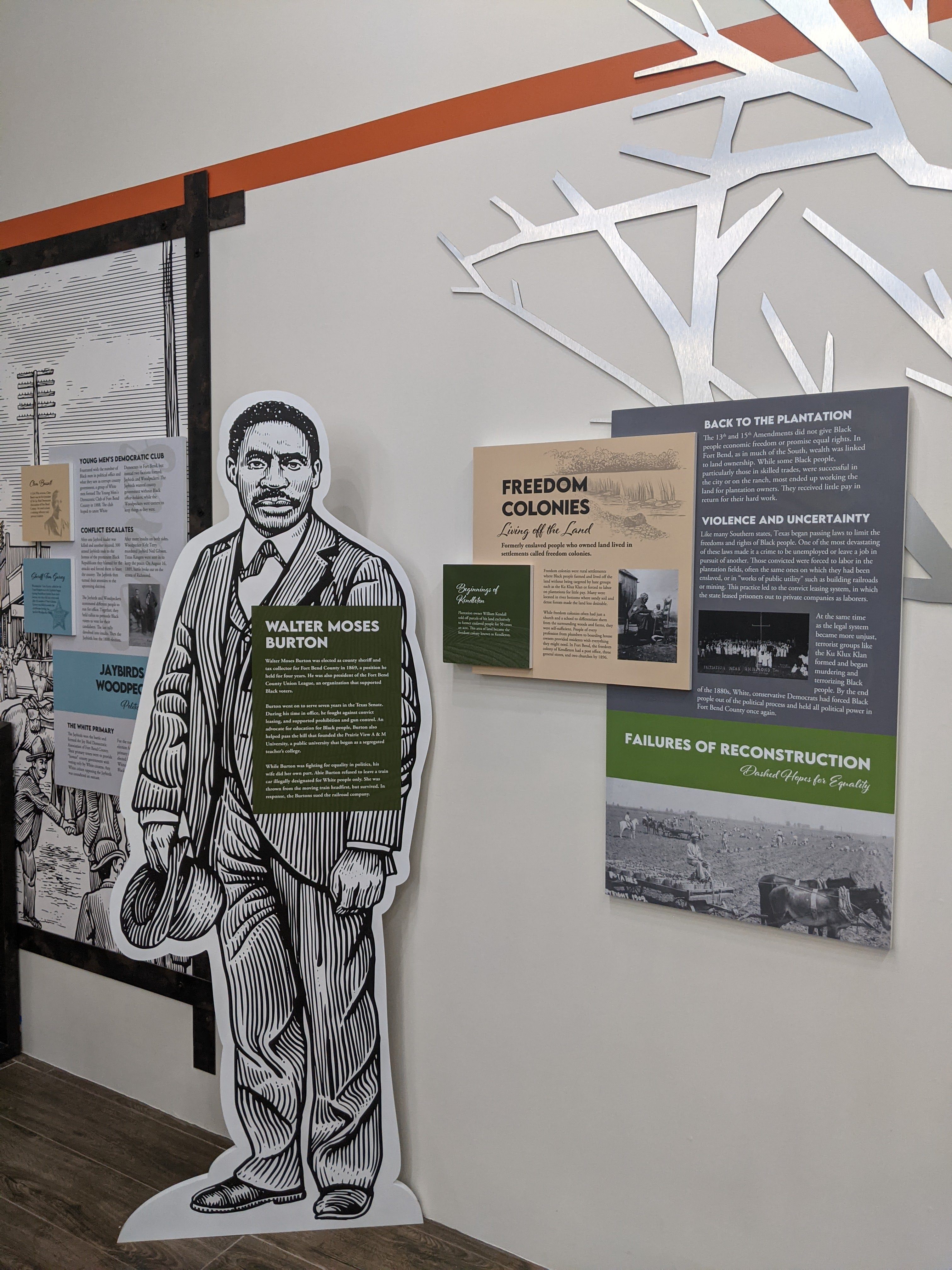

Today, Burton’s legacy is subtly preserved throughout Fort Bend County. An elementary school in Fresno is named after him (its mascot is aptly named the Burton Sheriff). The Fort Bend Museum, located a short walk from Morton Cemetery where Burton is interred, features a small exhibit on Burton’s life, including a life-size cutout of him.

In Sugar Land, about 30 miles southwest of Houston, a group of Black citizens are also pushing to rename a street—currently endowed with a plantation owner’s surname—after the Texas senator.

“He’s someone that was a prosperous farmer, a politician—he was born into slavery,” says Captain Paul Matthews, 77, one of the residents spearheading the initiative. “If you want to tell the story of America, the full story, this is a good example.”

During the pandemic, Morton Cemetery drew a steady trickle of Texans and tourists eager to get outside amid statewide safety restrictions. The cemetery, which was founded in 1825, houses the remains of more than 4,000 former local residents.

Visitors are especially drawn to Burton’s memorial, according to cemetery manager David Kaack. He notes that the former county sheriff was also the first Black man buried in Morton Cemetery, alongside his son, Horace.

“It’s history,” Kaack added. “He’s the first elected Black sheriff in the United States. That’s pretty big in my book. People just want to see that.”

Burton’s memorial is open to the public year-round, seven days a week, at Morton Cemetery in Richmond.

This post is sponsored by DEVELOP Richmond TX. Click here to explore more.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook