Sandwiched between Park Avenue and Third Avenue, just east of Union Square, is the small stretch of city street known as Irving Place. Extending south from Gramercy Park it was once a fashionable district of artists, actors, and the crème-de-la-crème of Gilded Age high society. At the southwest corner of 17th Street and Irving Place sits a small two-story house of red brick, curiously out of sync with the other houses around the area.

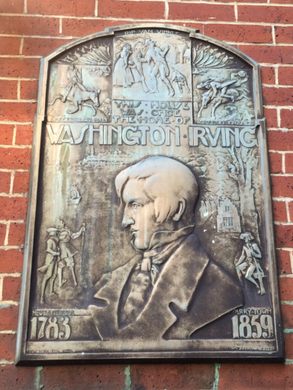

While this home and several dwellings behind it along 17th Street are all of the same basic design (and were all preserved as NYC Landmarks in 1998 as the “East 17th Street/Irving Place Historic District”), the house at the corner, 49 Irving Place, is decorated just a little more than the others. While all are preserved, stories say that this house was once home to famous early-American writer Washington Irving. A large bronze plaque on the north side of the “Irving House” confirms his involvement here. There’s just one little problem.

Irving never so much as crossed the doorstep.

So why the story? If he never lived there, how has it come to be known as his house? To figure that out, we’ll have to go back a few years.

The Irving Place area was first developed in the 1830s, extending eastward from the recently established Union Square Park. The property encompassing the area belonged to Cornelius Williams, and had been in his family since 1748. In 1832, realizing that he could no longer prevent the city from running streets through his land, Williams began leasing the area to developer Samuel B. Ruggles. Ruggles was instrumental in the planning of the area, being part of the coalition that developed an enclosed park bordered with a private residential community at the northern end of Williams’ farm that he named Gramercy Park, as well as petitioning the New York State Legislature to run a parallel street between Third and Fourth Avenues. Above Gramercy Park, this new street was called Lexington Avenue, in honor of the Battle of Lexington. Below Gramercy, Ruggles named the area Irving Place in honor of his friend Washington Irving.

The “Irving House” was built by Peter Voorhis between 1843 and 1844, along with the adjacent two houses at 45 and 47 Irving Place. The original tenants of 49 Irving Place (at that time referred to as 122 East 17th Street) were Charles Jackson Martin, an insurance executive, and his wife, who would reside there from 1844 until 1852. Henry and Ann E. Coggill would live in it in 1853, and in 1854 it would become the home of banker Thomas Phelps and his wife Elizabeth, who would remain until 1863.

Various other occupants would come and go over the next 40 years, including Charles A. Macy, a member of a wealthy merchant family and uncle of the department store founder, but its most celebrated residents would move in in 1892. Actress Elsie de Wolfe and her partner, theatrical and literary agent Elizabeth Marbury, would occupy the house until 1911 and it was during this period that the Washington Irving story would begin to circulate.

As for Irving himself, he was a minister to Spain in 1844 when the house was built and wouldn’t return stateside until 1846 when he would retire to his estate north of New York City called Sunnyside, a property in Tarrytown, New York that he acquired in 1835 and would spend much time and money fixing up. He would pass away at Sunnyside in 1859. Thus, it is highly unlikely he ever had dealings with the house at 49 Irving Place.

But what of the story? The first mention in print of Irving having lived in the house came in the Sunday Magazine Supplement of the New York Times on April 4, 1897. The article is a human interest story about Elsie de Wolfe and the means and methods she used to decorate “Irving’s house.” In 1905, de Wolfe would become known as the first professional interior decorator and it appears this article is an early attempt at publicity for her. As for the information about Irving, the article takes enormous liberties (actually, it flat-out makes things up), claiming that Irving had conceived of the house himself and was very particular about the architecture and design. Whether Ms. de Wolfe knew the story was a fabrication and used Irving’s name to lend credibility to her efforts, whether the newspaper writer mentioned Irving to make the story flashier, or whether either person was simply passing down a story they had been told by someone else, we’ll never know.

Although it bore no connection to Irving, the house did play host to de Wolfe’s popular intellectual salons, which at various points boasted such Gilded Age dignitaries as architect Stanford White (for whom de Wolfe decorated the Colony Club) and society queen Isabella Stewart Gardner.

In 1927 an effort was undertaken to preserve the houses in the 17th Street area and another article appeared in the Times on August 24th, specifically mentioning the historical value of “Irving’s house.” This prompted a letter to the editor published on September 12th from a Ms. Emma M. Lewis (likely the daughter of Thomas and Mary Lewis, who lived at 47 Irving Place from 1856 to 1871):

“I have been much interested to read about the Washington Irving house at 122 East Seventeenth Street, and especially the letter giving the names of the owners for years past.

I have lived all my life in that neighborhood and, as a girl, was in this house hundreds of times while it was owned by the Macys.

In those days it was never even mooted that Washington Irving had ever lived in the house, but he was said to have boarded one Winter in a house at the southwest corner of Sixteenth Street and Irving Place. His nephew, Pierre Irving, lived at 120 East Seventeenth Street. His daughter, Mary, a very handsome girl, married the son of Huntington, the artist. I knew her.

After Elsie de Wolfe came to live at 122 East Seventeenth Street it was rumored that Washington Irving had lived in that house and that he used to sit in the second-story windows ‘to watch the boats in the East River.’ This was repeated in one way or another so many times that it was taken for truth.”

-Emma M. Lewis, New York, September 9, 1927

And yet, despite no evidence and Ms. Lewis’ outright denial, the story continued to grow. In 1930 a restaurant called the Washington Irving Tea Room was operating in the basement of the building and in 1934 a plaque sculpted by Rodin-student Alexander Finta was put up on the north facade that would cement the story in the public consciousness. Today, the surrounding area remains covered in references to Irving, from the large art installations in the nearby W Hotel to the Headless Horseman pub on 15th Street.

Community Contributors

Added by

The Atlas Obscura Podcast is Back!

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook