The Art of Micronations: Rebellion through Creative Land Conquests

Once the domain of only the most determined of oddballs, micronations are a more common phenomenon since the advent of the internet. These days, you don’t even need a physical territory to declare yourself a head of state — you only need a website — and even if you do have a property to claim, a populace of fellow oddballs to be your country’s citizens is a lot easier to come by when you have access to the whole world’s supply.

The difference between a nation and a micronation is a small but important one: A micronation is one that’s not officially recognized by world governments. Also, a micronation is usually, but not strictly, a secession from an established nation. Beyond that, there are two general conventions that define the conditions of statehood: The Montevideo Convention requires a) a territory, b) a permanent population, c) a government, and d) the facility to enter into discussions with other states, while the constitutive theory of statehood adds a fifth criterion: the recognition of the rest of the world as a separate state, which disqualifies the vast majority of micronations.

Either way, if we’re counting virtual space, i.e., on the internet, all of this is a lot easier to attain and document online than it used to be. But back in the day, it took some hardcore chutzpah, creativity, and organizational skills to pull this feat off — emphasis on the creativity. It’s no surprise, then, that so many of the first micronations were established by artists. Here are a few of the most original ones we’ve come across.

THE REPUBLIC OF ROSE ISLAND

In 1967, Giorgio Rosa, an Italian artist and architect, funded and spearheaded the construction of a 4,300-square-foot sea platform in the Adriatic Sea between Cesenatico and Rimini. Originally, he did this under the premise of it being a tourist destination, and it was replete with a night club and a gift shop.

But on May 24, 1968, immediately upon completion of construction, Rosa declared sovereignty from Italy, dubbing the platform “Insulo de la Rozoj” (“The Republic of Rose Island” in the universal language of Esperanto, which Rosa declared his new nation’s national language, the only place to ever do so).

After hiring employees to help run the new nation, Rosa then named himself the President, instated a crest, and issued a number of stamps depicting the republic’s approximate location, 6.8 miles off the coast of northern Italy. The Italian government didn’t do much until Rosa announced several days later that he would be printing up his own currency, which gave them cause to think he would use it as a platform to avoid paying taxes on his tourist trap.

They responded by sending the military police to evict Rosa and his employees. Then, on June 29, the Italian Navy showed up with explosives and blew the entire structure up, just 55 days after sovereignty had been declared. As a sassy riposte, Rosa printed up another batch of postage stamps, bearing an image of the platform being dismantled, and issued from Rosa’s self-declared government in exile. Since the island was destroyed, however, Rosa stopped exercising his rights as a citizen, although the legend of Rose Island lives on in the form of a 2008 play, a 2009 documentary, and a semi-abandoned Facebook group.

THE KINGDOM OF ELLEORE

Located not far from Copenhagen in the Danish Roskilde fjord, the tiny, kind of crescent-shaped island of Elleore was purchased in 1944 by a group of school teachers who purported to use it as a summer camp.

Instead, they established a tongue-in-cheek independent kingdom as a sarcastic gesture to the Danish government — as well as to Nazi Germany, which had been occupying Denmark since 1940. Erik I, Elleore’s first king, was crowned a year later, followed by a new king (and, once, a queen) every decade or two. Seventy years later, with its original population no longer in the picture, the island, also named Elleore, sees its citizens only one week per year, during an annual holiday wherein the dozens of nationals claim to be returning home after a 51-week vacation. Elleore has no permanent structures; its citizens camp in tents during their stays. Legally, it’s still a part of Denmark

Although it was started as a flip-off toward Denmark’s royal and governmental traditions, Elleore is run as kind of a Monty Pythonian joke these days; its place names are satirical versions of Danish ones, and it observes Elleore Standard Time, which is 12 minutes ahead of Central European Time. Elleore does issue stamps and coins, though, sort of straddling the border between complete joke and actual micronation. It probably can afford to be more of a joke now that Denmark isn’t occupied by the Nazis and things are little more chill.

NEUE SLOWENISCHE KUNST

Its name translating to “New Slovenian Art” in German, this collective of Yugoslav political artists announced itself as a separate state in 1984, back when Slovenia was still a part of Yugoslavia. The avant-industrial band Laibach originated from the group, taking the German name of the Slovenian capital city, Ljubljana, where the collective was founded.

Its territory is not physical but “confers the status of a state not to territory but to mind, whose borders are in a state of flux, in accordance with the movements and changes of its symbolic and physical collective body.” So a floating castle sort of idea (but not a cyber-castle, as NSK wasn’t founded online).

NSK’s art style is an ironic jab at totalitarian and nationalist movements, especially Nazism, appropriating symbols and juxtaposing them with opposite concepts. It also frequently reappropriates political kitsch and borrows from Dadaism.

In 1992, just a year after Slovene independence was established, NSK began organizing embassies and consulates in cities around the world, so far in Moscow, Ghent, Berlin, and Sarajevo, which host various events for its citizens. NSK also started issuing passports around this time, although they’re considered to be works of art and not actually valid for travel.

These passports and embassies are what NSK claims sets them apart as a micronation rather than an art collective. Some refugees have been scammed over the years, purchasing NSK passports from Nigerian and Egyptian sellers, ostensibly for more than the €24.00 they’re currently selling for on passport.nsk.si. Even though it didn’t begin on the internet, NSK is mostly based there today, and its thousands of citizens reside around the world, on six continents, helping to further the nation’s principles of anti-totalitarianism and transnationality.

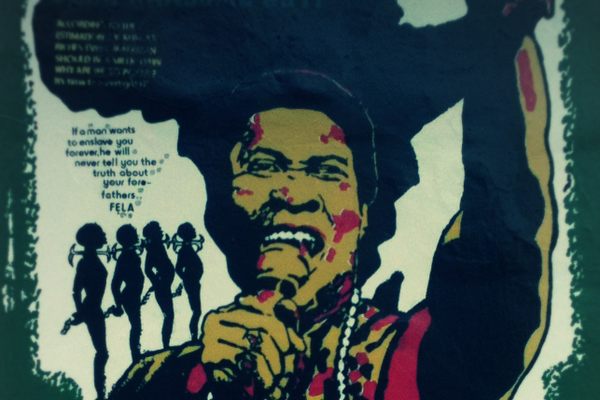

Wheatpaste of NSK’s art, often posted in public spaces (photograph by Vuk Cosic)

THE REPUBLIC OF KUGELMUGELIt seemed like a good idea at the time, when artist Edwin Lipburger decided one day in 1984 to build a 25-foot ball-shaped house in the Lower Austrian countryside. This worked out fine for a while, until a dispute arose between Lipburger and the Austrian government over building permits, giving Lipburger the choice of having it destroyed or moving it to community property. The authorities relocated the whole house to an amusement park in Vienna. Lipburger responded by declaring his house, named Kugelmugel (kugel, “sphere,” and mugel, an Austrian-German expression for a small hill) to be an independent republic, and himself its head of state.

Not long after his arrival in the park, Lipburger began printing his own stamps and announced that he would not be paying taxes, as all micronational leaders must, whereupon the Austrian government took him to court and he received a 10-week prison sentence for his trouble. A last-minute pardon from President Rudolf Kirchschläger kept him from actually going to prison.

Surrounded by a barbed-wire fence, Kugelmugel still stands in the amusement park, Vienna Prater — at 2, Antifaschismusplatz 1 (2nd district, Anti-Fascism Square, No. 1), sharing the street with a little café. Although the republic itself is no longer operated by Lipburger, his ghost nation is (only outwardly) accessible to curious tourists during park hours. photograph by Peter Gugerell

LADONIA

Dr. Lars Vilks began building a series of sculptures out of 75 tons of driftwood on the shores of Sweden’s Kullaberg nature reserve in 1980. This was followed by construction on a stone sculpture nearby in the same year. The structures were named Nimis (Latin, “too much”) and Arx (Latin, “fortress”), respectively. Then nothing happened, because the pieces, although very large, were in difficult-to-reach areas of shoreline, accessible only by boat or a strenuous 45-minute hike, and nobody knew about them.

Two years later, the local council discovered the sculptures, which they deemed to be buildings and which were forbidden to be constructed on the reserve, and they were ordered destroyed.

Vilks didn’t take them down, though. After many appeals, all of which he lost, the case went to the Swedish government, whereupon it was finally settled in the council’s favor. While all of this was going down, Vilks sold the driftwood pair of structures to monumental artist-couple Christo and Jeanne-Claude in 1984 and he therefore refused to take them down on the grounds that they no longer belonged to him.

In 1996, with Vilks and the Swedish government still immersed in a court battle, Vilks declared Ladonia, the land the sculptures were built on, to be a separate state. The flag, a green field with a faint white outline of the Scandinavian cross, is alleged to depict what the Swedish flag would look like if boiled. All of Ladonia’s citizens live abroad and they number over 15,000; citizenship is available online for free, with titles of nobility costing $30. Taxes are payable only in creative labor, the interpretation of which is left up to the applicant.

The nation is ruled in tandem by a queen-for-life, Carolyn I, and a president and vice president, who are elected tri-annually. Vilks himself serves as the state secretary and manages passport applications as well as the Ladonian newsletter. The country has not one but two national anthems: One is a tone poem on the development of freedom in Ladonia, and the other is performed by throwing a rock into the water.

A new stone-and-concrete sculpture, Omphalos, appeared in Ladonia in 1999, at over five feet tall and weighing a metric ton. After some rigamarole involving complaints being filed to police by a Swedish arts foundation, artist Ernst Bilgren purchased the piece just before it was ordered demolished by the district court, which sent a bill to Vilks for 92,500 Swedish krona as a dismantling fee. Afterward, Vilks applied to the council for permission to erect a monument for Omphalos, which was granted, as long as the memorial built was no more than eight centimeters high. Vilks complied, and the memorial was inaugurated in 2002.

Nimis (photograph by Sebastian Vidovic)

Arx (photograph by Hakan Dahlstrom)

LIZBEKISTAN

Speaking of creative micronations, we will conclude by giving a shout-out to (seemingly) the original online territory.

As part of a larger project on citizenship, Australian artist Liz Stirling invented a virtual, internet-based micronation in 1996, back when it was a hot new idea, declaring herself “Princess, Absolute Monarch, and Virgo,” at lizbekistan.com. As the nation was not founded on any physical territory, it was considered more of a concept than an actual micronation, but it was popularly “inhabited,” with several thousand citizens, called Lizbeks.

According to its site, the virtual nation was planned over regular real-life cocktail hours, and eligibility was open to anyone, provided he or she was willing to contribute content, tech help, logistical aid, cash, or some other kind of assistance to the project. Lizbekistan had a currency, called the “nipple,”and produced passports, stamps, and several online newspapers, including but not limited to the state-run State Newsletter, The Lizbek Sentinel, and Galasnost, all written and published by sundry Lizbeks.

Despite being lovingly produced and well-maintained, Lizbekistan was doomed from the start. Stirling established it with an expiration date of 9-9-1999, which is when Stirling “blew it up,” leaving her homeless Lizbeks with the (now also defunct) lizbekdiaspora.com and, Stirling’s most recent project, lizvegas.com.

Discover more micronations on the Atlas Obscura >

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook