Wild Life: Synchronized Coral Spawning

In a preview of our new book, we watch the world’s largest living structure renews itself in nights of moonlit passion.

Each week, Atlas Obscura is providing a new short excerpt from our upcoming book, Wild Life: An Explorer’s Guide to the World’s Living Wonders (September 17, 2024).

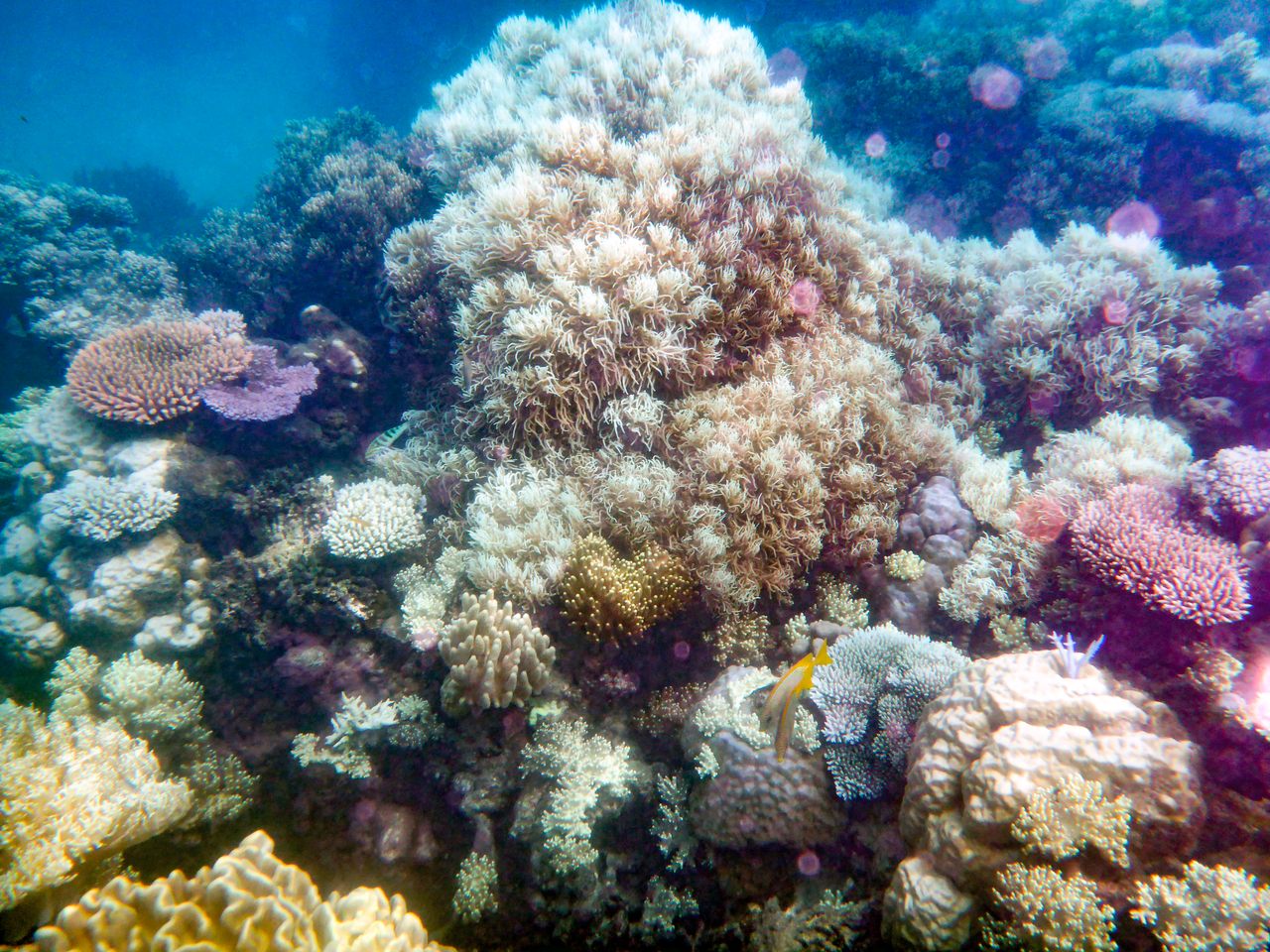

Once a year, the corals of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef pull off an orgy so massive it can be seen from space. Warmed by the water, tugged by the tides, and sparked by the full moon, coral polyps release eggs and sperm in a vast cloud. The buoyant bundles of gametes rise to the surface, forming vast slicks shaped by ocean currents.

As adults, the tiny animals that build and make up coral reefs are immobile, stuck in their own magnificent skeletons. They reproduce asexually throughout the year, cloning themselves into expanding colonies.

But because they cannot swim to find each other, they must achieve the genetic reshuffling that comes from sexual reproduction in a different way. Most use a signal that is both reliable and romantic: the full moon.

Polyps detect the moon’s state with cryptochromes, a type of receptor that can sense blue light. Different species wait different lengths of time after the full moon to let loose, generally between three and five days. “They’re very synchronized,” says Muhammad Abdul Wahab, a benthic ecologist at the Australian Institute of Marine Science. Some species patiently hold their gametes until the right time and then let them go. Others spew without warning, like volcanoes. Mushroom corals—which are solitary, enormous polyps—become visibly plump and then, about 30 minutes before sunset, eject their eggs. If you’re diving around the reef at the right time, you’ll see and feel a flurry of coral reproductive packets in hues of red, orange, and yellow.

Once the bundles reach the surface, wave action breaks them apart and fertilization occurs. Within 24 hours, tiny coral embryos develop. The resulting larvae, most no bigger than sesame seeds, drift here and there.

After four or five days of mobility—the only time these animals will experience movement—the larvae sink to the seabed and decide where to settle. They must find a place populated by the symbiotic algae upon which they depend while avoiding being eaten by a grazing fish or bulldozed by a snail. Wherever they end up, Wahab explains, “they have to be content for the rest of their lives.”

As the coral polyps begin constructing their calcium carbonate skeletons, they’re rebuilding the Great Barrier Reef, which has been severely damaged by the warming and acidification of ocean waters. If they survive and grow, they too will get the chance to participate in the moonlit rite that regenerates this living structure.

- Range: 1,400 miles (2,250 km) of reef in the Coral Sea, off the coast of Queensland

- Species: The Great Barrier Reef is made up of hundreds of species of coral, many of which participate in full-moon spawning events.

- How to see them: Scuba diving is the best way to experience this event for yourself. Check with local dive shops to coordinate your visit, because timing is everything. Great Barrier Reef coral typically spawn during the first week of the full moon in October or November.

Wild Life: An Explorer’s Guide to the World’s Living Wonders celebrates hundreds of surprising animals, plants, fungi, microbes, and more, as well as the people around the world who have dedicated their lives to understanding them. Pre-order your copy today!

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook