A Cookbook for Dining With the Dead

Learn to make amaranth skulls, “buried” tamales, and other regional Día de Muertos recipes.

Ghosts eat well on the Day of the Dead. In cemeteries across Mexico, carefully placed baskets of pan de muerto and tamales sit among graves, while altars, or ofrendas, honoring the deceased are adorned with hot chocolate, pozole, and chicken legs coated in mole negro.

It’s these earthly pleasures that will lure dead loved ones back from the afterlife. “You have to ask, “What is it they cared about and would return to re-experience?’ says Mariana Nuño-Ruiz McEnroe, author of Dining With the Dead, a cookbook of traditional and modern recipes for celebrating Día de Muertos that they published last year.

McEnroe, a Guadalajara native, co-wrote the book with her husband to highlight the regional varieties of holiday traditions. There are recipes for the Yucatán’s mukbil pibipollo, a pie-like tamale that gets “buried” and cooked in an underground pit; querubines Oaxaqueños de pan de yema, sweet loaves of bread that Oaxacans shape into bodies and top with little cherub masks; and cornudas tradicionales de cinco picos, five-pointed tamales that are a specialty of Michoacán’s traditional cooks.

Gastro Obscura spoke with Mariana and her husband, Ian about their book, how different regions celebrate Día de Muertos., and what foods would lure them back from the afterlife.

What are your favorite recipes from the book?

Mariana Nuño-Ruiz McEnroe: I love the mukbil pibipollo. I think it’s very unique in its flavor. I also absolutely love pan de muerto. And hot cocoa dulce because it’s perfect at night—that’s what people have at the cemetery on the night vigils. I also love frijoles de olla, which is just beans in a clay pot.

That’s what I want on my ofrenda. Give me that—the flavor, the licorice of the broth—with something simple like avocado, some queso fresco, salsita from the molcajete, and I’m the happiest person in the world.

Ian McEnroe: There’s a recipe for street enchiladas in the book, which are really different from the American-style preparation. It’s a much looser sort of wrap and just the way they sauce them, plate them, the ingredients they use, it’s all just delicious.

For me, they bring back memories to the time when we were out eating street food in Michoacán. Also, buñuelos, which are these delicious super-thin fried tortillas with sugar and cinnamon. It’s hard not to like those covered in syrup.

You did a lot of research in Michoacán, especially around Lake Pátzcuaro. Can you tell me a bit about your experiences there?

MM: Pátzcuaro has very beautiful traditions because of the Indigenous Purépecha that live all around the lake. So we went around its islands just to see how it was celebrated. It was wonderful, but at the same time, it was a little awkward because you’re wandering around a cemetery and these are people’s loved ones.

Honestly, [in the United States], people think Day of the Dead is a big party. And, yes, it’s joyful; people in Mexico are joyful that their departed are visiting them. But if you go to the cemetery, you’ll also feel respect. It’s serene, peaceful, not like a crazy fiesta. Still, it was a great experience, and it was just one of the most beautiful things I’ve ever seen.

How do you think Día de Muertos traditions help people memorialize the dead?

IM: It lets you memorialize, but in a very kind of casual way, whereas, in the States, when we memorialize, it tends to be a very sad or severe kind of occasion. And that’s appropriate sometimes. But just when it’s somebody passing because of old age, it’s more like “Didn’t she like this and didn’t she enjoy that?” And those are the things that become part of the tradition. And, suddenly, they’re back with you, in a way.

How does this influence what gets put on the ofrenda?

MM: The basic building blocks for an ofrenda are some candles, some marigolds, pan de muerto, a photo of the person that you’re honoring, and the things that they enjoyed in life. Those elements of the ofrenda are meant to lure the soul back from the afterlife.

So you can put out some pan de muerto and join in those traditions, but you should put out whatever it is that you think would attract them, because that’s the whole point of it.

IM: For Americans trying to make an ofrenda, there might be the temptation to find a Latin store and stock up on things that are supposed to be on an ofrenda. And that’s cool to have something traditional. But if people are going to go out and make their own, then I think it really has to be about the loved ones they’ve lost. And that’s the bittersweet side of it. You have to re-experience what you shared, what they cared about.

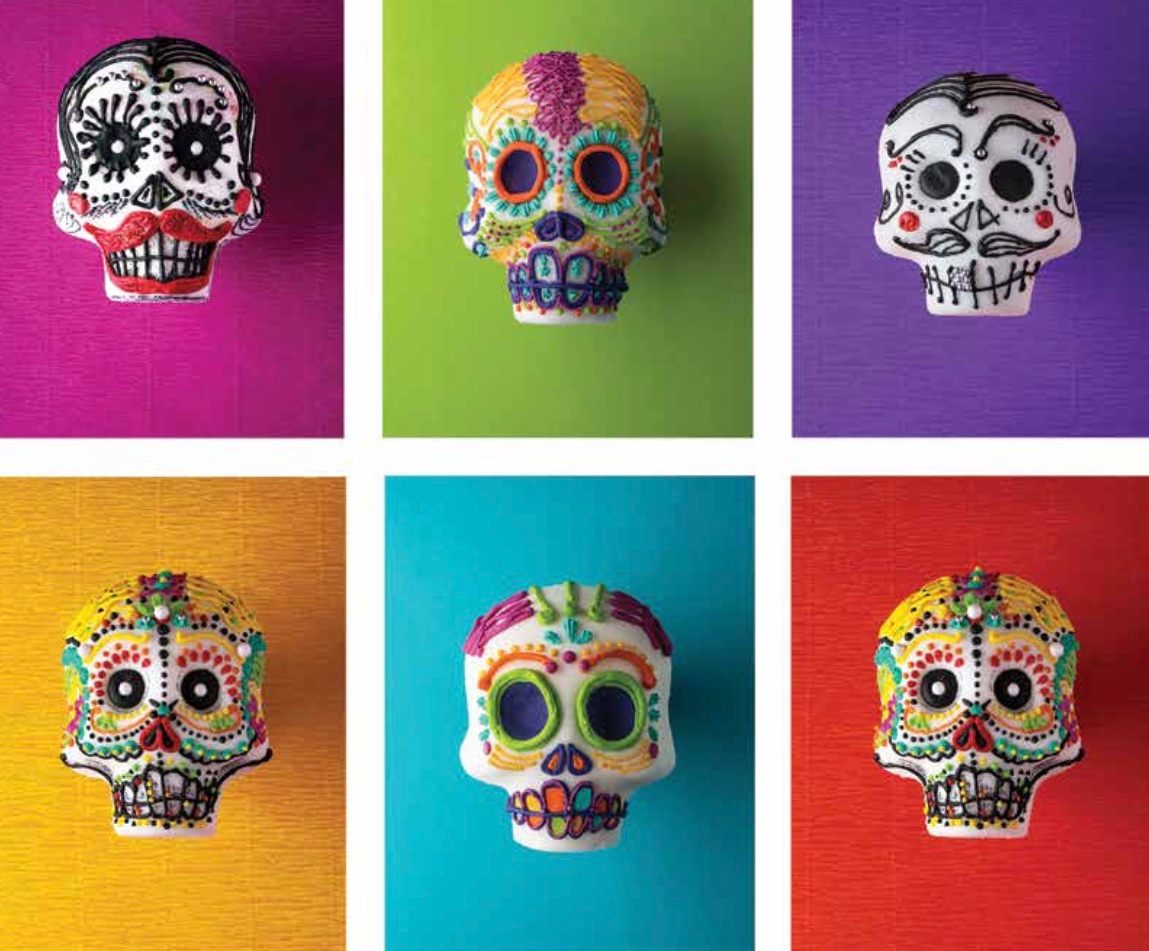

In addition to the food, I’m very accustomed to seeing sugar skulls on an ofrenda. Your book offers instructions on how to make those, but I was also happy to see the book’s recipe for amaranth-and-honey skulls, which aren’t quite as ubiquitous. Can you tell me a bit more about those?

MM: In Mexico, rituals were originally based on corn and amaranth. The Aztecs used amaranth seeds that they puffed with some honey and created big totems [of the god Huitzilopochtli].

By the time the Europeans arrived in Mexico, they prohibited [amaranth] because it was a symbol that the Aztecs still believed in their gods. Then, after the revolution, people started rescuing amaranth seeds and using them again.

Today, amaranth sweets are common in certain areas of Mexico, like Xochimilco [a borough of Mexico City]. They’re usually sold in markets as little squares that are kind of like Rice Krispie treats. In the fall, they make skulls. Little ones, big ones. They also mix chocolate and amaranth together for a skull. It’s really good. It has a very nutty flavor.

You’ve celebrated the holiday, worked on this book, visited all these people. What has this shown you about the importance of food on Day of the Dead?

MM: For me, being Mexican, food is always the point of a gathering. You show love with food. You show generosity, kindness through food. If there’s a birthday, if somebody’s sad, if somebody’s angry, if somebody’s happy, you have food. We just gather around the table, celebrate, and that’s what you can offer. And it’s the most honest offer you can make to somebody, right? Here, I made this with my hands.

IM: The thing about a lot of the recipes in the book is that they aren’t necessarily made by just one person standing alone at a stove. It’s a family that comes together.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

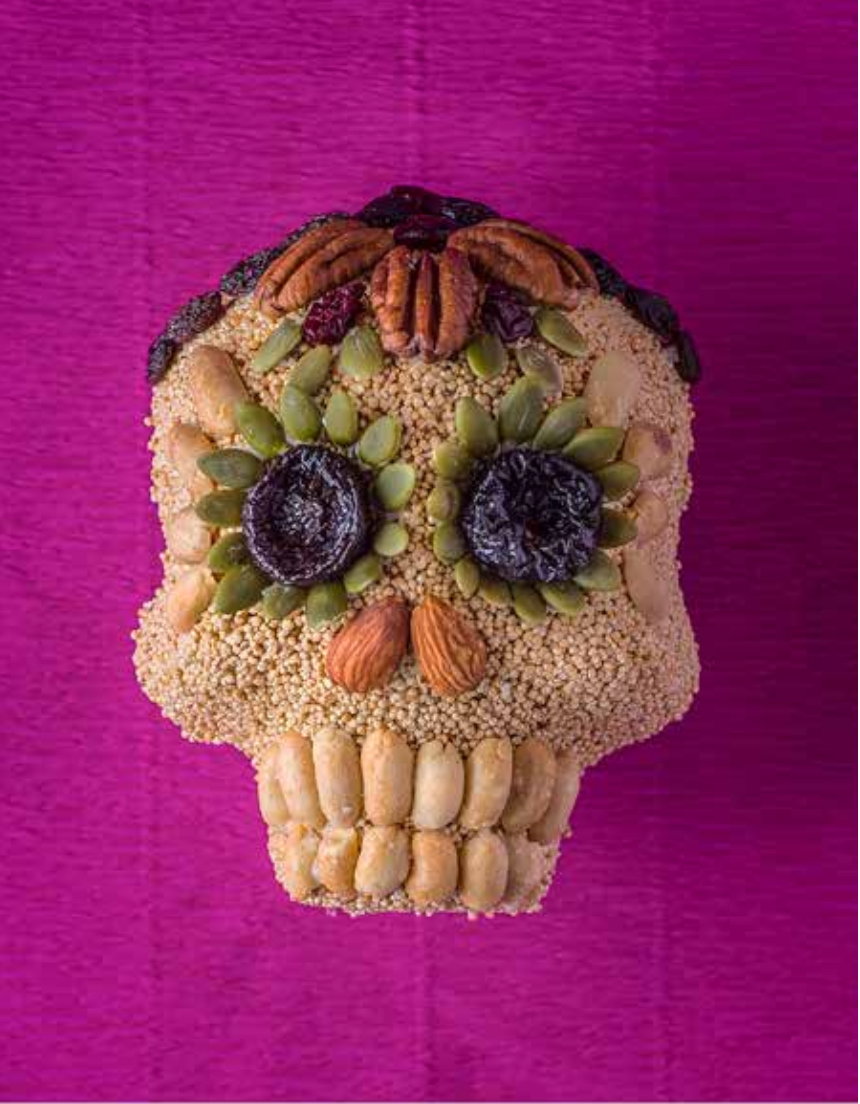

Amaranth and Honey Skulls

From Dining With the Dead

- Makes 2 large amaranth skulls

Ingredients

- ¼ cup water

- 150 grams piloncillo sugar, grated

- ½ cup honey

- 1 teaspoon lime juice

- 16 ounces puffed amaranth

- 2 pinches ground cinnamon

- Royal icing, seeds, and dried fruit, for decorating

- 1 or 2 large skull molds*

Instructions

-

In a small pot, heat up the water and piloncillo and stir until the piloncillo dissolves. Add the honey and lime juice, and bring to a low simmer. Stir constantly until half the liquid has evaporated and it has the consistency of honey. Remove from the heat and let the syrup cool down, for two to three minutes.

-

Add the puffed amaranth and gently stir using a wood spatula. Once the amaranth is cool enough to handle, rub your hands with some cooking oil and gently knead the mixture until the syrup is evenly distributed.

-

Promptly fill two skull molds (see note below) and press down to get a solid skull. If the mixture is too sticky, add more oil to your hands. Level and even out the back of each skull. Place a piece of cardboard behind the mold and flip it over. To help release the mold, tap on the skull, forehead, and chin. Let the skull dry for about 24 hours. The next day, carefully glue the two skull halves together using the royal icing.

-

At this point, your skull is still fragile but dry enough on the outside to decorate. Use royal icing to glue seeds onto the face. Mariana McEnroe uses pepitas around the eyes, prunes for the eye cavity, roasted peanuts for the forehead and teeth, two almond halves for the nose, and pecans for the top of the skull.

- These skulls are edible within two to three days, and good to display for more than a month.

Notes and Tips

* You can buy these online.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook