The 10th-Century Master Chef Who Wrote Food Poetry

His verses offer a glimpse into the good life during the Islamic Golden Age.

Kushajim, the 10th-century polymath, poet, and master chef, once described a certain snack in verse:

I have for friends when hunger strikes, qata’if, like piles of books stacked.

They resemble honeycombs—with holes and white—when closely seen.

Swimming in almond oil, disgorged after they had their fill of it.

With glistening bubbles, back and forth, rose water sways.

Rolled and aligned like purest of arrows, their sight the smitten-hearted rejoice.

More delicious than they are is seeing them plundered, for man’s joy lies in what is most hankered.

(Translated by Nawal Nasrallah)

Qata’if are sweet fritters stuffed with nuts and fried, and they’re still popular today, especially during Ramadan. In literature, they have long been depicted by poets as symbols of desire and love, a tradition that dates back to Kushajim and his culinary verses.

Kushajim’s work features in the earliest known Arabic cookbook, the 10th-century Kitab al-Tabikh. Compiled by Ibn Sayyar Al-Warrāq, a scribe in Baghdad, the book is a snapshot of the haute cuisine of the Abbasid Caliphate. First translated into English by the historian Nawal Nasrallah and published in 2010 as Annals of the Caliphs’ Kitchens, it contains 615 recipes, as well as 24 poems by Kushajim. These verses, which ranged from culinary odes to musings on etiquette and society, offer an invaluable glimpse into the good life during the Islamic Golden Age.

Of Indo-Persian ancestry, Kushajim was born in 902 near modern-day Tel Aviv. During his life, he journeyed through the cities of Jerusalem, Damascus, Baghdad, and Cairo before finally settling in Aleppo. His actual name was Mahmud ibn al-Husain ibn Ibrahim ibn Shahik al-Sindi. Kushajim was an acronym he devised himself, with each letter in Arabic representing a title (scribe, poet) or trait (benevolence). Though Kushajim did become a prominent literary figure, his real claim to fame was his position as the court cook for the Hamdanid ruler of Aleppo, Sayf al-Dawla.

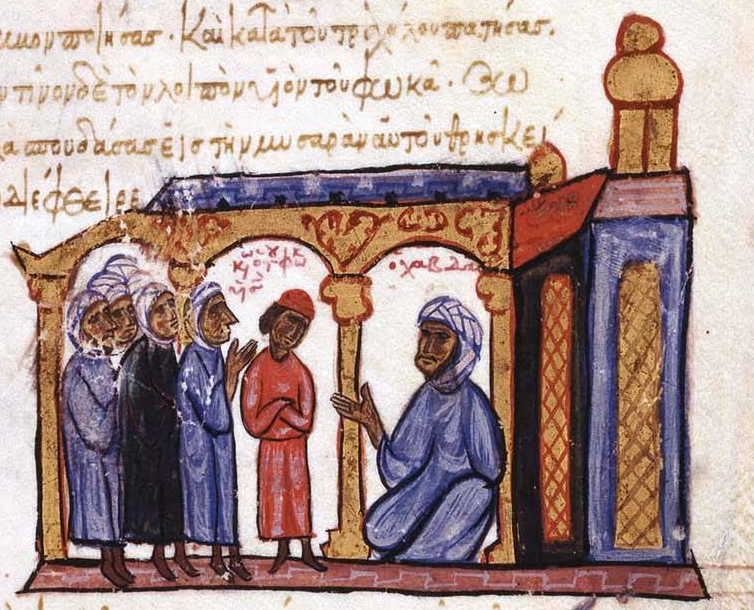

Kushajim’s royal boss was well-known for his military victories and lavish lifestyle, but also for his cultural interests. In the introduction to Annals of the Caliphs’ Kitchens, Nasrallah writes that Sayf al-Dawla earned the title al-tiraz al mudhahhab, which means “golden royal robe.” What this meant was that he had surrounded himself with excellent and intelligent people, much like wrapping himself in a lavish robe.

Kushajim was a part of this golden circle. According to Nasrallah, it was the fashion of the age for noblemen and even the caliphs to discuss cooking techniques and food. This coincided with the arrival at the court of new vegetables, spices, foods, and cultural influences from far-off places. Nobility encouraged both poetry and writing about food, making Kushajim’s skills a huge asset.

Salma Harland, a British-Egyptian literary translator and scholar, is currently researching and translating Kushajim’s life and poetry. “His gastronomic poems are vivid with hyper-sensory details,” she says. “He not only names the dishes, their ingredients and cooking methods, but also all the scents and flavors, and how they influence banquet-goers once they see the serving platters coming their way.”

But Kushajim’s position as a court cook was also extremely important. The personal chefs of the king not only supervised the cooking, but also ensured that only the right foods were cooked according to the humoral disposition of the ruler. The Greco-Roman concept of humoral theory was prominent during the Golden Age of Islam, and medical and culinary texts often included instructions on eating to adjust “humors” such as blood and bile. Kushajim would have had to ensure that the food cooked for the king was healthy and also enjoyable. Simply put, he had to have been a master chef.

Not much is known about Kushajim’s work and personal life. A note on the poet in Annals of the Caliph’s Kitchen says that he was married and had two sons. Harland adds that Kushajim’s grandfather was a high-ranking vizier in Caliph al-Mansur’s and Harun al-Rashid’s courts. Kushajim wrote on a wide range of topics besides food, from musical instruments to chess. Books written by Kushajim which survive to date includes one on etiquette and good manners (Etiquette of the Boon-Companion), another on music (The Characteristics of Music), and a book on hunting (Book of Snares and Game) which is considered to be the earliest extant book in Arabic on the topic.

Kushajim also occasionally wrote poems addressing his family. In a poem he admonishes one of his sons, asking him to be kind to his parents if he wishes to receive benefits in the afterlife. But one thing that no longer exists are any of the cookbooks he was known to have written. According to Nasrallah, while other writers reference cookbooks written by Kushajim, none have survived. However, his recipes and food poems live on in Al-Warrāq’s 10th-century cookbook. One of his poems in the book, about inviting a friend to a meal of left-over dishes, highlights how people of the era cherished food and friendship:

Hurry up to our only pot. But we also have braised meat cold and set,

And our cook I believe still has leftovers of the cold lentil dish,

Saffron-gold and sweet and sour which an ailing stomach can cure…

We have dense honey pudding like cornelian. It wearied the hands that stirred.

Awe-stricken diners when first see it, will prostrate fall for it.

(Translated by Nawal Nasrallah)

Kushajim looms large in both the Abbasid gastronomic and literary scenes, notes Nasrallah. “He was a great poet, and was recognized as such even during his lifetime,” she says. In his book Meadows of Gold and Mines of Gems, the 10th-century Arab historian Al Masudi describes a symposium of food conducted by the 22nd Caliph of the Abbasid Caliphate, Al-Mustakfi, who reigned from 944 to 946. At his court in Baghdad, the caliph hosted gatherings where guests would discuss different varieties of food and recite food poems. One night, several attendees recited works by Kushajim.

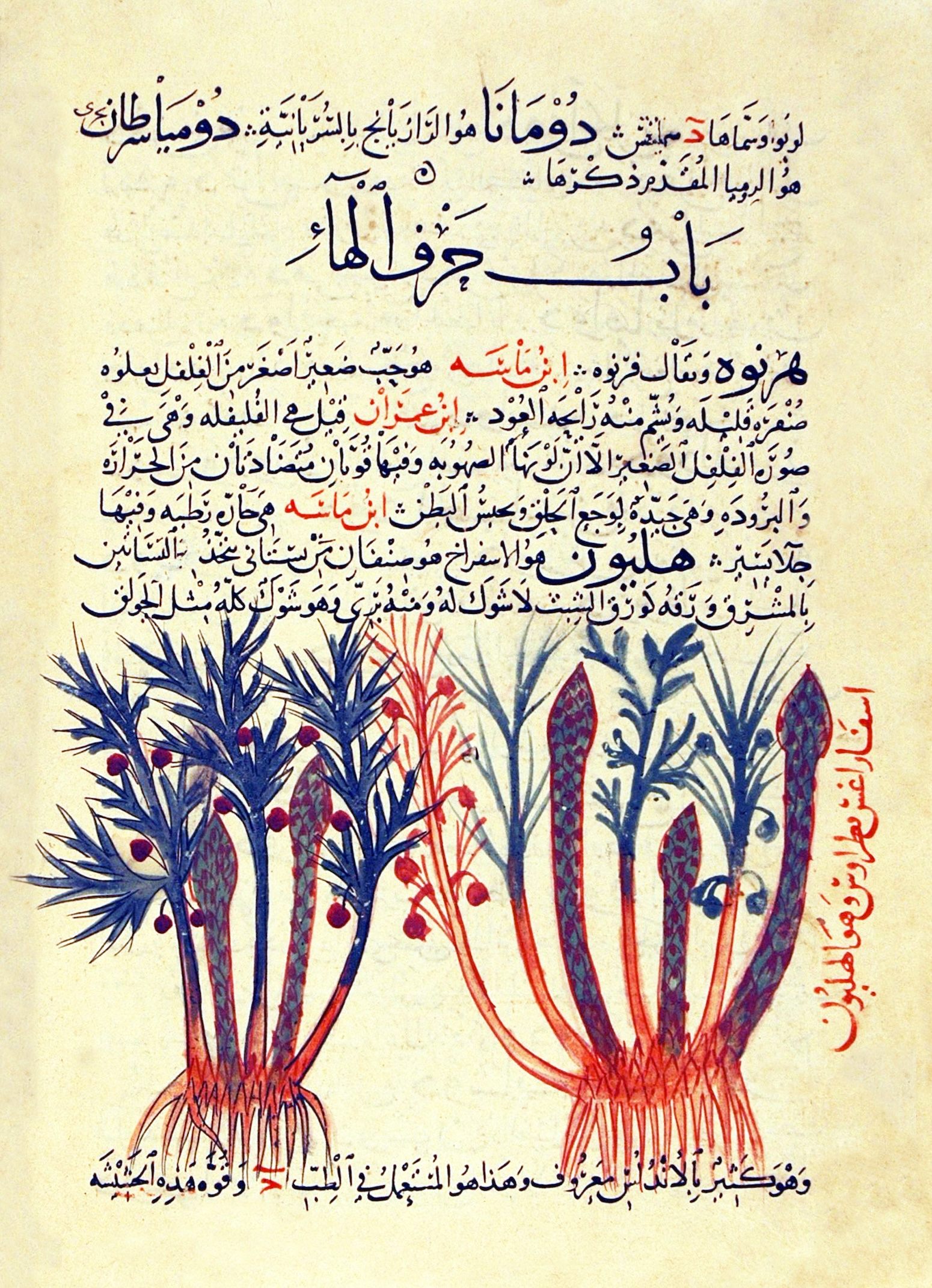

One poem was all about asparagus, comparing the rosy tint of the vegetable to “hands turned red in a silver bowl filled with ice.” Kushajim also rhapsodized over their shape, noting that when lined up, asparagus spears looked like “neat embroidered goldwork adorning the hemline of finest silk.”

The poems delighted the caliph so much that he immediately ordered that every dish mentioned in them should be brought to him immediately. For the asparagus, the caliph declared that he would ask the commander of Egypt to send some to the court, since it was not available in Baghdad.

Kushajim’s gastronomic poems provide us with images of the cuisine and food customs in the medieval Arab world, preserving the tastes of a bygone era. “The various subjects of food, ranging from recipe-poems, descriptions of food items, hunting, fine dining, and camaraderie still resonate with us today,” Nasrallah says. “After all, the subject of food is universal and timeless.” Though the banquets are over and the plates have all been cleared, Kushajim’s poems saved future readers a place at his table.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook