Meet the Woman Preserving 125 Years of Black History in Baltimore

The “Afro-American” is in her blood.

For decades, the history of Baltimore’s Black community was filed away—somewhat chronologically, in banker’s boxes and bound volumes. It was stored with care, but without enough space or the expensive climate control measures to ensure long-term survival. This archive of the country’s longest-running Black family-owned newspaper—the Afro-American, which still publishes today—got its start as what’s known in the newspaper industry as a morgue, a resting place for reference files of newspaper clippings in the days before Google. Now Savannah Wood, the great-great granddaughter of the paper’s original owners, plans to bring life back to the collection of more than 125 years of fragile newsprint and irreplaceable photographs.

Atlas Obscura spoke with Wood about her family legacy, the future of the Afro-American’s past, and plans for a new home for the archive in West Baltimore.

How did the Afro-American get its start?

There was a paper that existed for five years called the Afro-American that was founded by other folks, and our family purchased it in 1897. So, the two founders, as we call them, of the newspaper are John Henry Murphy Sr. and his wife, Martha Elizabeth Howard Murphy. Martha was the one who gave her husband $200 to purchase the paper. The money came from the sale of a piece of land that Martha’s family had been enslaved on in Montgomery County, Maryland. They eventually came to own that land, and Martha sold her portion of it to invest in her husband’s business.

That’s the origin story of the Afro, which I find to be pretty amazing. My ancestors gave me some big shoes to fill. I am kind of in awe about all that they accomplished in their lives, with such great challenges stacked against them.

Was the newspaper always a part of your life?

Growing up in the Bay Area, almost every summer we would visit my grandmother in Baltimore. She had “Camp Granny” and all of her 16 grandchildren would go to church with her. We learned how to set the table properly. And we sold newspapers on the streets of Baltimore and Washington, D.C.

But like most young people I wasn’t super-interested in the historical aspects of my own family lineage, so the newspaper didn’t have a huge influence on me growing up. It took me a while to circle back and truly understand the profundity of what my ancestors had done and the fact that the newspaper still existed.

Why are the Afro-American archives so important to Black history?

The collection includes so much information about world history, as told from a Black perspective. It’s always a slightly different take than you might get from mainstream media organizations. And it is also an archive about the people of Baltimore, of Richmond, of all the cities where the Afro-American eventually operated. These archives belong to the folks who are documented within the pages of the Afro.

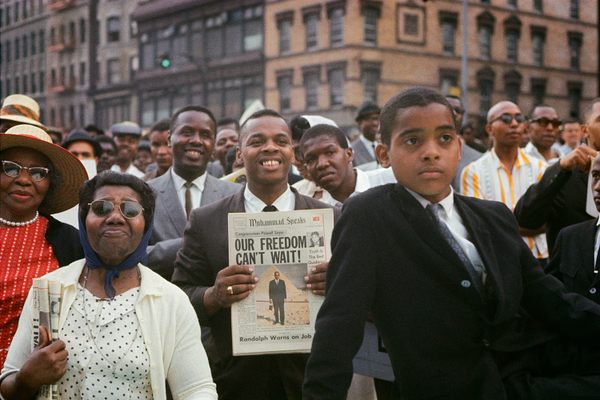

There are something like three million photographs in the collection. Some are people everyone will recognize—celebrities and politicians—but others are people you might not be familiar with. It could just be like, here is this group of neighborhood kids, and we have everybody’s name in the caption. There will be an opportunity for family members to be able to search this collection and find out, what did my aunt look like at age eight?

What untold stories do you hope people will find in the archives?

There’s so much to the collection beyond the newspapers and photographs. We have pamphlets from events that Afro employees might have gone to and organizations they were involved with such as the NAACP, the Urban League, the National Association of Black Journalists. And there’s business records for the Afro itself. There’s so much content there.

Personally, one of the things I think about a lot are the people who are supportive of the main characters we hear about. In our collection, you might see an image of Rosa Parks with four other people. Everybody knows Rosa Parks, but who are the people standing with her? What role did they play in the wider civil rights movement? What can we learn about their lives? I’m curious to learn more about these communities around the main characters, if you want to call them that, in our history.

How will the public access the archives?

Researchers don’t currently have access—first the coronavirus pandemic limited access to the collection and now we are moving it. And it is frustrating, but ultimately we’re building the capacity to give unprecedented access to the collection.

We’re undertaking a pilot program to help us understand what it will take to digitize and organize all the images. We’re starting with files that may have been put together for Carl Murphy, a former publisher and son of the founders, that features a lot of prominent figures. And there is a historic building in West Baltimore that we are redeveloping as a permanent home for the archives, where people can actually handle these materials and we can have programming for the neighborhood. We want to make sure that people have access to their history. This isn’t just the history of the Afro-American. It is the history of the whole community—of the whole country.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook