The Decadent Diet of Aleister Crowley

From sex-magick oysters to fantastical haggis, his diaries reveal an adventurous gourmand and accomplished chef.

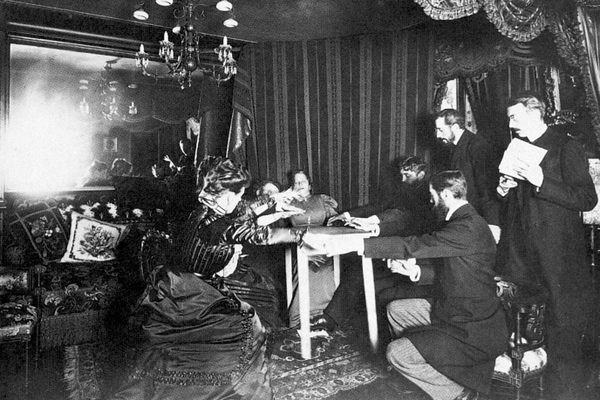

Controversial and colorful British occultist Aleister Crowley (1875–1947) was a man of many epithets, known variously as “The Wickedest Man in the World,” “The King of Depravity,” and even “The Beast 666.” He was praised as an accomplished mountaineer, poet, novelist, painter, chess master, and philosopher. He was also maligned as a drug addict, hedonist, and sex fiend. But another apt descriptor, though rarely mentioned, greatly shaped much of his life and writings: He was the ultimate gourmand.

Since he was a man of passion with Rabelaisian appetites about all manner of experiences, it should come as no surprise that Crowley embraced fine food and drink. But he paired excess with connoisseurship: Peppered throughout his personal diaries are hand-written recipes, detailed notes on wines, critiques of restaurants, and analyses of the varieties of foods to consume or not consume before certain “magickal” rituals.

Over the course of his life, Crowley traveled to Egypt, Mexico, China, Burma, Nepal, Germany, Algeria, Portugal, France, Japan, Scotland, and Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), among others. Throughout all these voyages, his personal journals—later published as Confessions—include extensive commentary upon the culinary offerings of the local cuisines, as well as restaurants and grand hotels in which he resided, such as London’s Savoy Hotel and its famed Savoy Grill, which boasted celebrity chef Auguste Escoffier at its helm.

In 1899, when he was just 22 years old, Crowley purchased Boleskine House on the southeast side of Loch Ness in Scotland. The home offered a bounty of salmon, deer, and game birds, all for the acquisition with fishing rod or hunting rifle. Richard Kaczynski, the author of Perdurabo: The Life of Aleister Crowley, says that Crowley’s love for salmon was a common theme in his writings and that “ready access to freshly-caught salmon may explain his disdain for tinned salmon, which he uses as a comparison for people or places he disliked.”

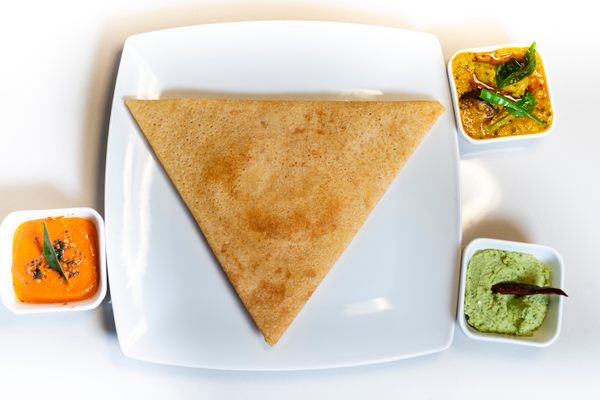

During his extended travels in the Far East and North Africa, Crowley developed a taste for spicy foods—a preference he honed on his mountaineering expeditions. On one of his earliest climbs, to Zermatt in Switzerland at the age of 21, Crowley perfected his fiery curry-making skills:

The weather made it impossible to do any serious climbing; but I learnt a great deal about the work of a camp at high altitudes, from the management of transport to cooking; in fact, my chief claim to fame is, perhaps, my “glacier curry.” It was very amusing to see the strong men, inured to every danger and hardship, dash out of the tent after one mouthful and wallow in the snow, snapping at it like mad dogs. They admitted, however, that it was very good as curry and I should endeavour to introduce it into London restaurants if there were only a glacier. Perhaps, some day, after a heavy snowfall—

Crowley’s treks proved him a prodigious and often trailblazing mountaineer. He took part in the first climbing attempt up the famed Chogori (K2) in 1902 and led a challenge on Kanchenjunga in 1905. It would be another 50 years before either of these great peaks would be successfully summited so these early attempts are quite noteworthy. Crowley’s provisioning lists for these mountaineering treks include voluminous tins of Danish butter and cases of Champagne, all to be hauled by his loyal and long-suffering sherpas.

Never a fan of canned food, Crowley’s diet of tinned food on expedition proved detrimental when gluttony overtook him during a trip through Baltistan in Pakistan. He wrote:

I made rather a beast of myself. I had been starving on canned food for nearly two months, and that half-warm, half-cooked fresh mutton made me practically insane. But never in my whole life have I tasted anything like that mutton. I gorged myself to the gullet, was violently sick, and ordered a fresh dinner.

A specific aspect of Crowley’s ritual use of food was for “magickal retirements,” meditative retreats he conducted prior to religious initiation ceremonies. According to Lon DuQuette, author of more than a dozen books analyzing and exploring the rituals of Aleister Crowley, a magickal retirement is a process of divesting. It is getting away from the distraction of the rest of the world, but documenting and tracking everything; moods, weather, sleep, sex, and—yes—foods eaten, and how these external forces affect you.”

Crowley’s two most well-documented magickal retirements occurred in Paris in October 1908, wherein he penned Liber DCCCLX (otherwise known as John St. John) and in 1916, when he stayed in a house owned by Evangeline Adams in Hebron, New Hampshire.

In Paris, during his first documented magickal retirement, he took an apartment that was a few minutes’ walk to the famed Le Dôme Café, the renowned gathering place for Belle Époque literati Ernest Hemingway, W. Somerset Maugham, and Anaïs Nin as well as artists Pablo Picasso, Vasily Kandinsky, Amedeo Modigliani, and Leonora Carrington. At Le Dôme, oysters were a favorite offering, which Crowley would “eat … in a Yogin and ceremonial manner,” chewing extremely slowly and deliberately, spiritually invoking their symbolic sexual power at the restaurant. As he described in his diary later:

O oysters! Be ye unto me strength that I formulate the 12 rays of the Crown of HVA! I conjure ye, and very potently command. Even by Him who ruleth Life from the Throne of Tahuti unto the Abyss of Amennti, even by Ptah the swathed one, that unwrappeth the mortal from the immortal, even by Amoun the giver of Life, and by Khem the mighty, whose Phallus is like the Pillar in Karnak! Even by myself and my male power do I conjure ye. Amen.

Crowley hired a personal chef when his funds would allow, but also prided himself on developing and cooking his own recipes. He was renowned for his curries and wrote a three-page explanation just for the preparation of rice to accompany them. In 1918, he brought a handful of acolytes to Boleskine, where he wrote an instruction manual entitled “Simple Cooking for Summer Campers,” declaring that “the following dishes and beverages have all been converted specifically to meet the needs of those who have gone back to Nature from the conflicts of life in great cities.” His Mixed Grill à la Boleskine is a testament to his gourmet tastes, complete with a diagram for each plate’s very specific placement upon the table:

- 2 devilled kidneys (Sauce Béarnaise)

- 2 Cambridge Sausages with 4 anchovies criss-cross over each

- 2 small rounds of caviar on toast

- 2 small rounds of soft roe on toast

- 2 large Mushrooms

- 2 half Egg stuffed with foie gras

-

2 Devils on horseback

Veg: Truffles stewed in Champagne.

Lest anyone take his gastronomic largesse too seriously, a page from his diaries displays two recipes quite at opposite ends of a culinary spectrum. One is a relatively simple guide to the preparation of Oeufs Vanity Fair which is nothing more than a classic soft-boiled egg, the necessary breakfast for any self-respecting Edwardian. The other, to Haggis Mère du Ciel (Mother of Heaven Haggis), is an entirely fantastical concoction stemming from Crowley’s sardonic wit:

Take Shark’s fin, Kangaroo tails, Bêche de Mer (sea cucumber), and Wombat kidneys with—if possible—Ornithorhynchus (platypus) livers. Mince finely and add Chinese Birds’ nests. Boil in Shark’s belly. Serve as a haggis, but with Chinese, Hawaiian or—better still—Maori music.

Kaczynski says that Crowley’s diaries’ lack of explicit instructions—“just listing the ingredients but not saying much about quantities or preparation”—reveals an experienced chef.“It really struck me how he was really into the cooking,” he says.

In his later years, Crowley seemed to truly flourish as a chef. His diaries describe May Day in 1938 as “a day of great social and gastronomical success” wherein he prepared a Sunday lunch of iced curry and chili con carne, Tournedos Gabriel (traditionally, grilled veal set on rounds of fried bread topped with a poached egg and crossed anchovies), surrounded by mushrooms chopped and tossed in butter with cayenne and birds’ eye (Thai) chili. However, Crowley noted that due to a lack of eggs, he had to tweak the recipe and make do with mustard and cream sauce. For 1939’s May Day offering—less than eight years before he would pass away—a 64-year-old Crowley served an upbeat luncheon for more than a dozen compatriots. Crowley prepared a chilled Gelée Cherbourg (prawns poached in fish fumet with soy sauce, cayenne, and cream).

Perhaps the king of depravity could have pursued the life of a chef de cuisine, instead of founding a religion, for this particular luncheon came with the chef’s verdict: “A great success this lunch, in some strange way; only explanation seems to be that I wasn’t there: just cooked and let them talk.”

In the end, Crowley’s culinary habits seemed largely focused on sharing a good meal with close friends. “ When he was flush with money from his inheritance, he would treat his friends to lavish dinners out,” Kaczynski says. “In later years, when he was broke, he seemed to expect others to do the same for him, even if those people were new to his circle. It was just what one did with friends.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook