Revisiting the Heyday of California’s ‘Crazy’ Novelty Architecture

Giant hats, portly pigs, and drive-thru donuts.

In the 1930s, a British traveler in Southern California wondered if the local architects had gone a little nuts. It was either that or he had stumbled into a fantasy universe. There was something trippy about the roadside shops he saw along the way.

A new, updated version of California Crazy, a book first released in the 1980s, recounts the unnamed visitor’s puzzlement. “If, when you went shopping, you found you could buy cakes in a windmill, ices in a gigantic cream-can, flowers in a huge flowerpot, you might begin to wonder whether you had not stepped through a looking glass or taken a toss down a rabbit burrow and could expect Mad Hatter or White Queen to appear round the next corner,” he wrote.

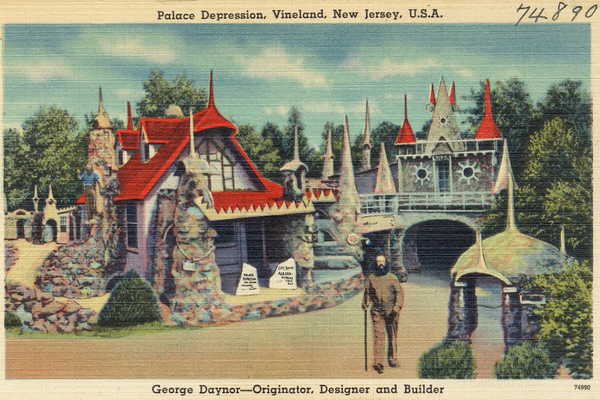

The unusual businesses he saw weren’t on some Hollywood backlot, but were California’s classic coterie of mimetic architecture—that is, buildings shaped like, well, anything but buildings. According to Cristina Carbone, a professor of art and architectural history at Bellarmine University in Louisville, Kentucky, the practice dates back to at least the Renaissance. By the 18th century, says Carbone, who is working on a book on the style, English gardens were sprinkled with follies, such as dining pavilions masquerading as pagodas, churches, and pyramids. In America, the first known example—a six-story wooden elephant named Lucy—rose over the seaside community of Margate, New Jersey, in 1881.

When this style of vernacular architecture landed in California a few decades later, it emerged into a sea of mission-inspired structures. But soon, these roadside curiosities—built with a wink and a whole lot of plaster—were perhaps more densely clustered there than in anywhere else in the world.

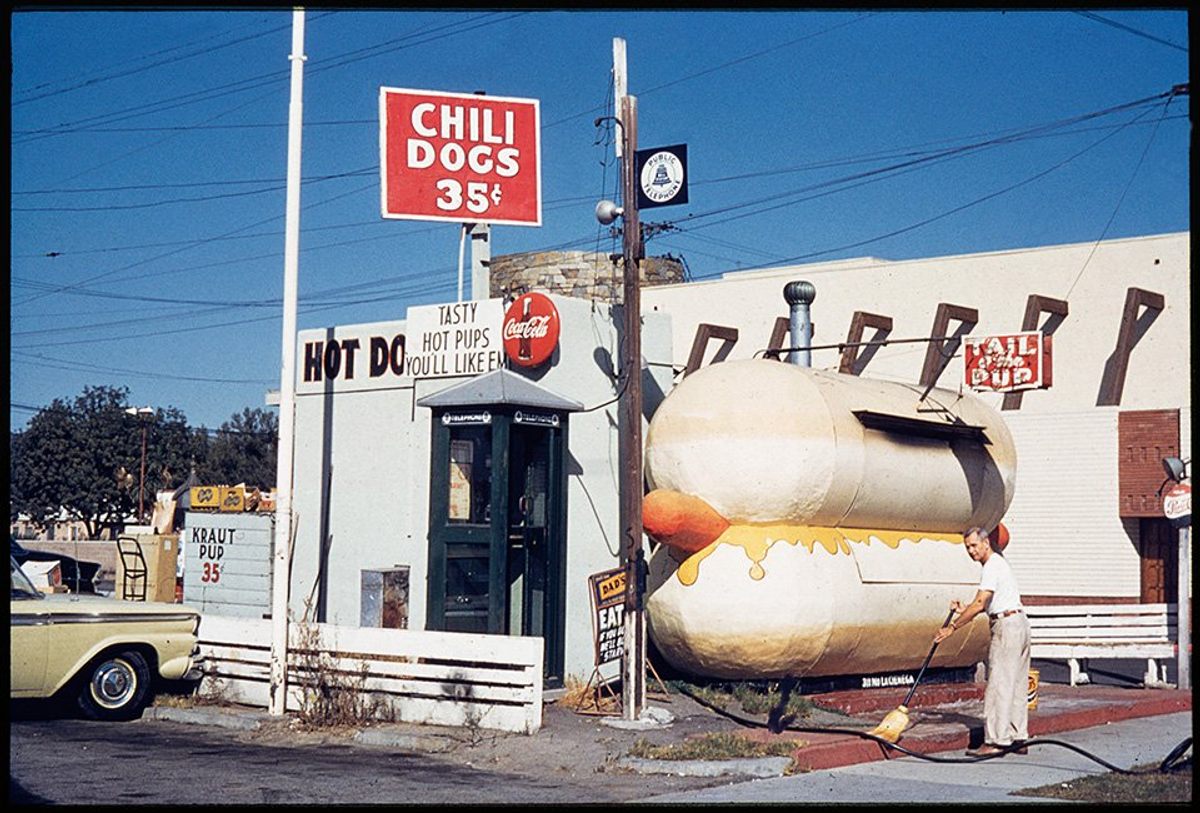

Though these buildings were rarely large, they were certainly hard to miss. Selling shoes? Try doing so from a shop designed to look like a giant’s oxford. Ice-cream cones? A curbside igloo that wouldn’t melt in the heat. Hot dogs? How about a classic doghouse?

In California Crazy’s essays and photos, Jim Heimann, executive editor of Taschen America, and late architecture historian David Gebhard, make a compelling case that these often-goofy buildings are more than just gimmicks—they’re cultural artifacts of a period that changed the landscape of America.

As California’s open spaces were tamed by roads and cars, business owners scrambled to find ways to entice drivers to pull off the highways and reach for their wallets. Automobiles became more widely accessible after World War I, and “the middle class was able to get out, and that had never happened before,” Carbone says. Mimetic buildings were, for a time, a useful tactic—both functional architecture and large, loud advertisement. “If Californians were going to be fully committed to this ‘automania,’” Gebhard writes, “then why not cultivate a set of architectural images which would instantly catch the eye, and which we would continue to remember?” These buildings were “not necessarily near anything terrifically important,” Carbone says, but they could draw the attention of drivers just passing through.

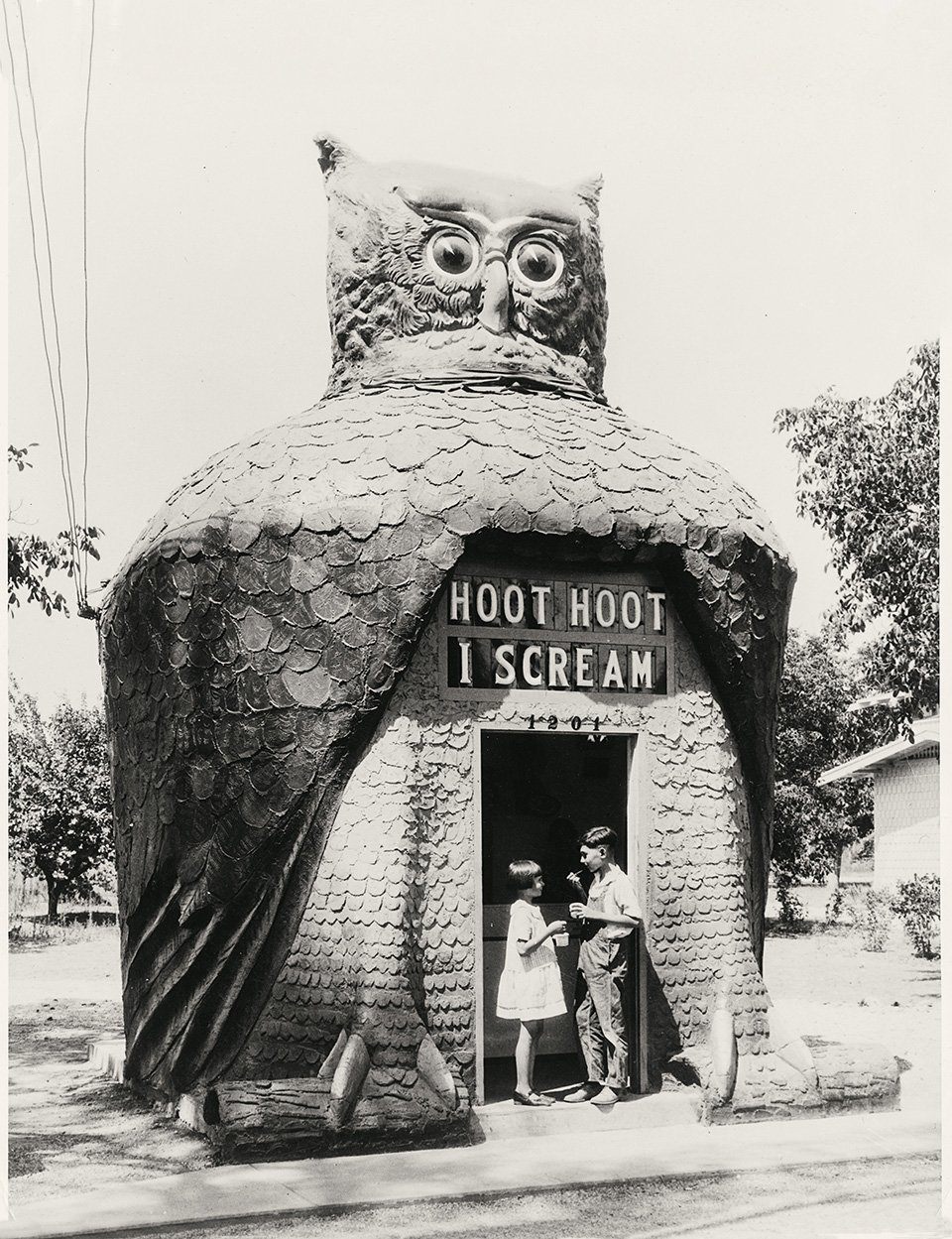

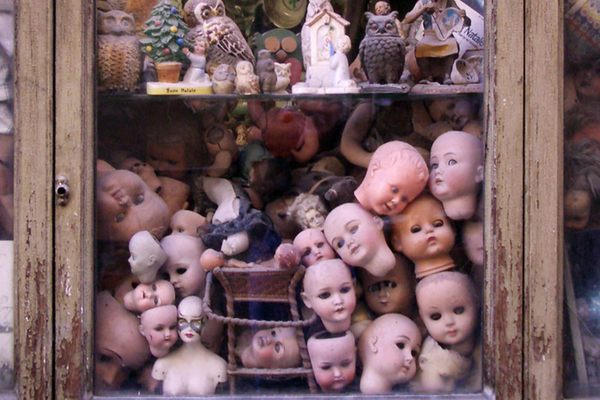

In a movie-obsessed city such as Los Angeles, teeming with creative folks and the set designers who brought ideas to life, there was no shortage of imagination and assembly skills. The owner of the “Hoot Hoot I Scream” stand, for instance, recruited movie-industry neighbors to help build a massive owl with headlights for eyes.

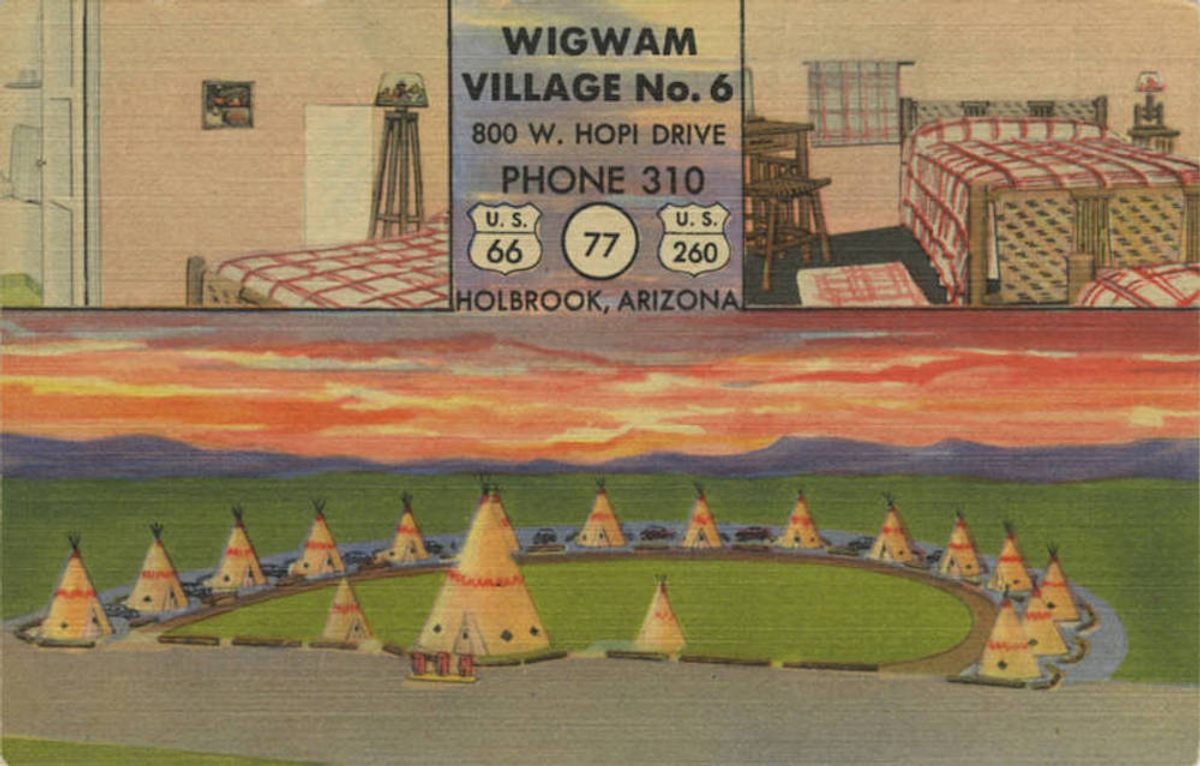

The result could be disorienting for out-of-towners. One 1928 visitor later mused to the Ice Cream Trade Journal that it was easy to mistake commercial strip for a movie set. “What else could a tourist think,” he recalled, “knowing by hearsay something of the prevalence of studios and the studio folk in that state, found himself whirling past gigantic ice cream freezers, snow block Eskimo igloos glowing in an electric aurora borealis by night, mammoth ice cream cones, and sparkling ice caverns, all established on the city streets or at vantage points along the open highway?” The buildings weren’t always literal, accurate, or culturally sensitive. They sometimes muddled fact, fiction, and fantasy, as was the case for a chain of “wigwam” motels, with stucco and concrete bungalows designed, contrary to the name, to look like tepees. (Three still stand, in California, Arizona, and Kentucky.)

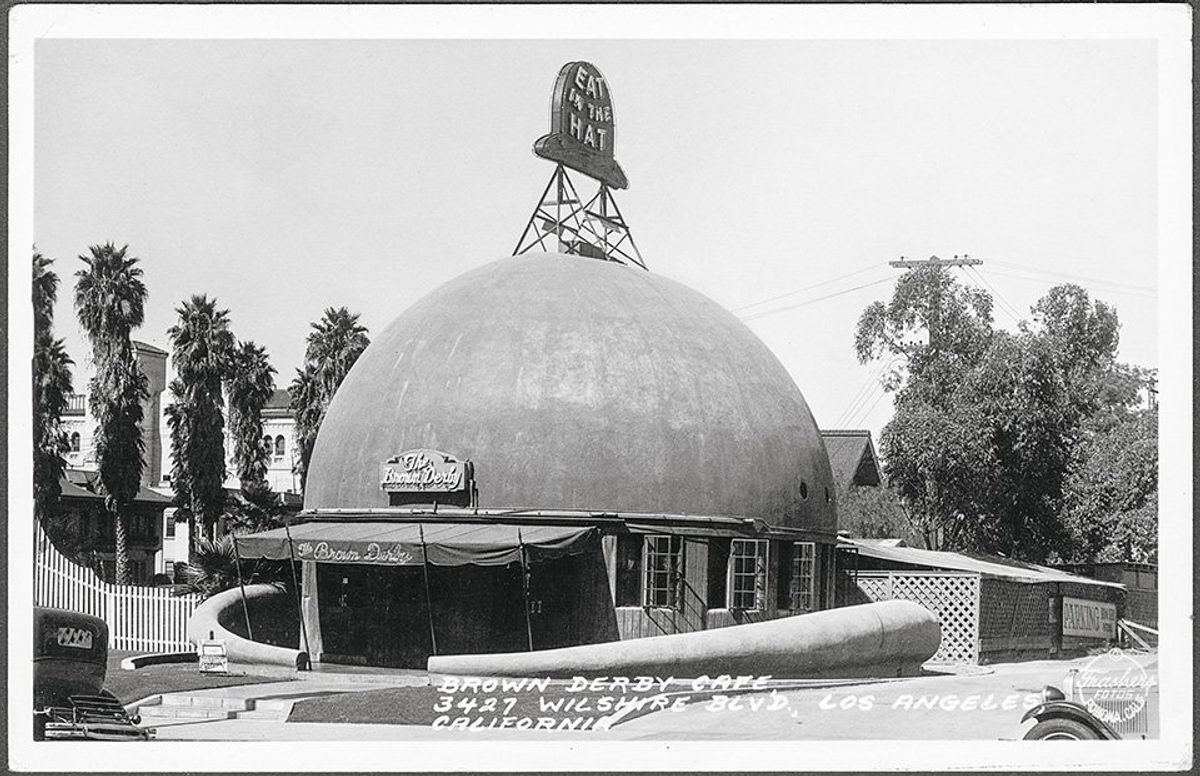

By now, many of these roadside curiosities—even the most well known—have disappeared or mutated. Take the iconic Brown Derby. The restaurant chain was an early adopter of the architectural style—each restaurant was shaped like a giant, jaunty chapeau. The first, on Wilshire Boulevard, opened in the late 1920s, and quickly became a place to see and be seen. The flagship hat moved a little way down the block in 1937, but eventually only the dome remained, and today rises from an otherwise forgettable shopping center. The Hollywood location came down in February 1994, after being damaged by an earthquake. Local preservation groups staged a funeral at the demolition, wearing derbies of their own. Today, Disney World has a replica, and an original sign is in the permanent collection of the Museum of Neon Art, though it spends most days in a warehouse.

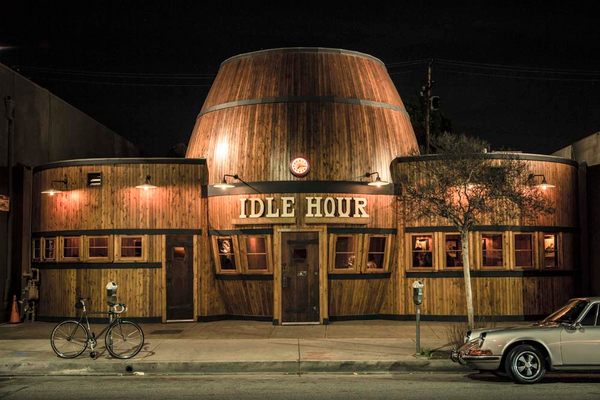

A handful of other mimetic buildings have hung in there. Lucy, the New Jersey elephant, was the first mimetic structure to be included in the National Register of Historic Places. “These buildings often are much-loved by the communities where they are,” says Carbone, who named her dog after the pachyderm. In California, community members have banded together to move some mimetic buildings. The Shutter Shak, for example, an enormous camera that was once home to a photo-developing business, is now in a historical park. In 2015, 44 years after it first opened, a Los Angeles bar shaped like a whiskey barrel was resurrected as the Idle Hour.

Though California will always have a place in its history, the center of the mimetic architecture scene might be going overseas. Though the Chinese government clamped down on “weird” architecture in 2016, mimetic buildings are still going up—such as a huge crab and an even bigger turtle. Carbone cites examples in Seoul and India, too. Maybe it will also pop back up again in California. “It was never really in fashion,” Carbone says, “and has never entirely gone out of fashion, either.”

Atlas Obscura has a selection of additional images from California Crazy.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook