In Canada, Gold Rush-Era Garbage Reveals a History of Chinese Immigrant Cuisine

Archaeologists unearthed evidence of pig roasts and boozy gatherings at an 1870s British Columbia eatery.

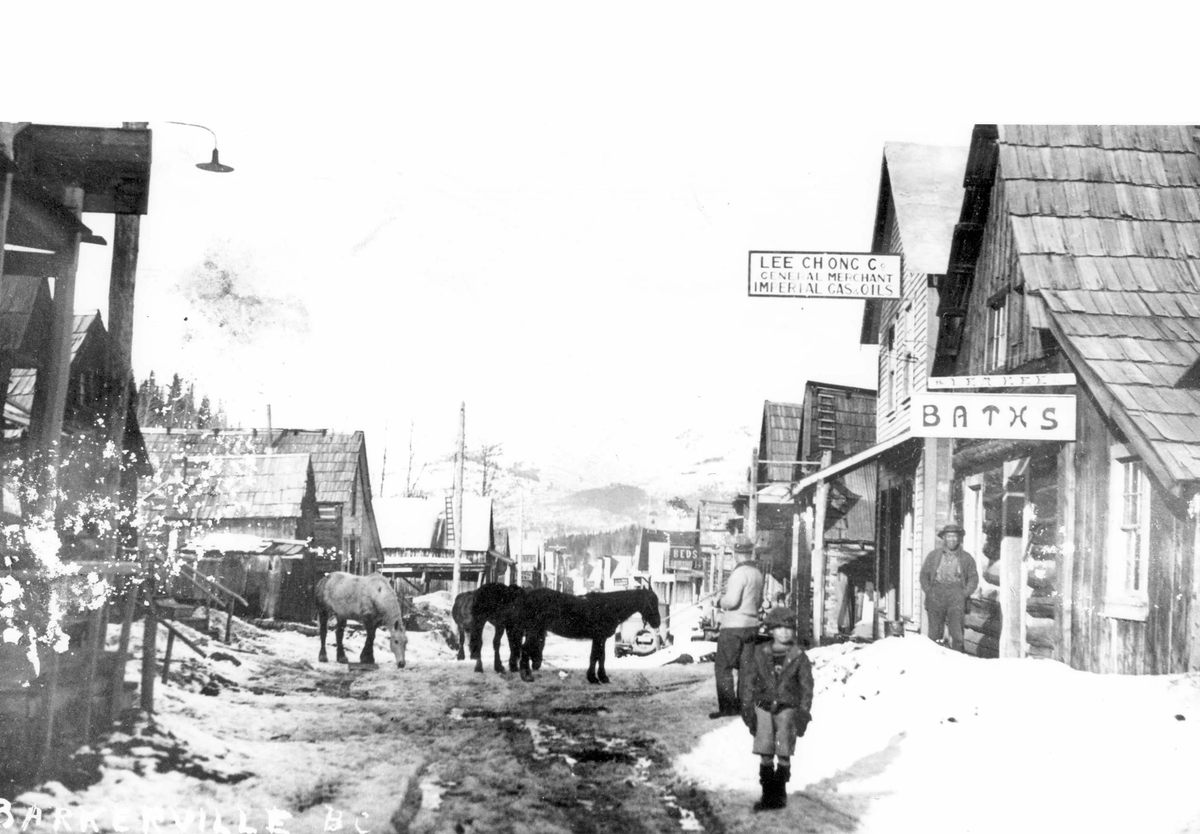

Dawn Ainsley, staff archaeologist at Canada’s Gold-Rush-era Barkerville historic town and park, was overseeing the installation of a new sewer line in 2012 when diggers struck a different kind of gold: garbage. “Every time we hit a garbage dump we had to stop and monitor it,” says Ainsley of the dig. The site of a largely Chinese-Canadian mining town established in the 1860s, and now an open-air museum, Barkerville is full of meaningful trash, the result of generations of household waste tossed off back porches and into alleyways.

But this particular garbage pit—or midden, in archaeological speak—wasn’t just off any old porch. It was located between two historic restaurants, the now-defunct Doy Ying Low restaurant, established in the 1870s, and the Lung Duck Tong, established in the 1920s, which continues to serve as an eatery for visitors today. When Barkerville staff started digging through the find, they uncovered a unique record of the daily culinary life of the thousands of Chinese-Canadian prospectors who had left China for the promised “gold mountains” of Western Canada’s mining towns. Findings included evidence of a century-old pig roast, dominoes and drinking parties, and one very old, still-intact piece of canned meat similar to Spam.

This summer, as British Columbia’s physical-distancing guidelines permit, Ainsley will continue excavating these culinary finds with the help of Barkerville visitors, part of a community archaeology program dedicated to bringing the history of the region’s Chinese miners to life.

Barkerville lies in the Fraser River Valley of what is now British Columbia, at the intersection of ?Esdilagh, Lhtako, Nazko, Lhoosk’uz, Ulkatcho, Xatśūll, Simpcw, and Lheidli First Nations land. European and Asian people were few and far between at Barkerville until the 1850s, when the wave of prospectors that had first migrated to California began to shift north in response to rumors of “easy gold” along the Fraser. By the 1860s, Barkerville—named for an early English prospector, Billy Barker—developed into a bustling mining town, with a peak population of 5,600 residents, half of them Chinese Canadian.

Barkerville’s Chinese miners were mostly young men, who migrated to the Americas hoping to strike it rich and head back home. “They never intended to stay,” says Ainsely. Faced with racism from white prospectors, they relied on Chinese-immigrant benevolent societies for community support, and quickly established their own networks of commerce and trade. By 1861, writes Tzu-I Chung, a history curator at the Royal British Columbia Museum, Chinese prospectors had established businesses—including grocery stores, general stores, and even opium dens—all the way up the Fraser River, including at Barkerville. Prominent among these gathering spaces were small restaurants like the Doy Ying Low.

Findings at the Barkerville restaurant middens indicate a rich community life, where single men decompressed from the backbreaking labor of the gold fields through communal meals and celebratory occasions like pig roasts. Ainsley has found numerous ceramics that Phillip P. Choy, a historian of Chinese immigrant material culture, identifies as everyday “folk ware,” min yao. These would have been used for eating and storing staples such as soy sauce, rock sugar, thousand-year-old eggs, and preserved vegetables, or jah choy.

“In situations where only male workers were present, such as in work camps for mines and railroads, and in seasonal agricultural work, each worker had his own porcelain rice bowl,” writes Choy. The workers would have eaten Chinese staples, like the above preserved vegetables and eggs, as well as beef and pork, and packaged foods like tinned meat. In addition to cafes like the Doy Ying Low, many of the miners would also have grown their own vegetables in terraced gardens along the hillsides surrounding town.

The middens also reveal a lively social life. “They liked to drink a lot,” says Ainsley. There was likely little else to do for fun considering the gold fields’ monotonous labor and relative isolation. Bottles from the site are impressively diverse, and many are imported, including a wine called ng ka py, which came in a signature spouted ceramic bottle, Japanese cider, and Filipino beer, all from no later than 1910. Opium was a common recreational drug. “Opium dens were among the earliest businesses established in Barkerville,” writes Chung, with both Chinese and non-Chinese communities partaking. In the 1870s, according to Chung, a bustling local drug trade made opium British Columbia’s third most valuable export, after only coal and fur.

Around 1900, Barkerville’s boom went bust. With the gold fields empty, a mass exodus of miners left the area. Many remained in Canada, reuniting with their families and sowing the seeds of a vibrant Chinese-Canadian culture. Their culinary influence, too, continues to color rural Canada, where Chinese restaurants founded by pioneering immigrant families remain a vital fixture. Other miners returned to their families in China. The lucky made it home alive. The unlucky, who died in the gold fields, often had their remains shipped back by benevolent societies to their communities in China as a form of final farewell.

By 1928, Barkerville had already become a National Historic Site. It was further labeled a Provincial Heritage Site in 1958, when officials decided to reopen it as a living-history museum, a function it continues to serve today. Yet signs of the Chinese miners remain, both in today’s Chinese-Canadian communities and in the artifacts of daily life that Ainsley and her team continue to unearth. Ainsley’s rarest find, a Qing Dynasty coin dating back to 1644, is particularly evocative. Qing Dynasty coins were in circulation in China until 1900, and it’s easy to imagine why miners in rural Canada would have wanted to hold onto them. Even amid the hard work and constant disappointment of the gold fields, many prospectors never gave up hope that they would strike it rich, and bring wealth to their families back home.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook