How Christmas Murder Mysteries Became a U.K. Holiday Tradition

In these Christmas tales, Santa has a very low survival rate.

In a family house beside a loch in Argyll, Scotland, just northwest of Glasgow, Andreina Cordani holds up the hard copy of her latest novel, The 12 Days of Murder. The cover looks like it’s wrapped as a Christmas present, with red and gold baubles framing the title, and the ‘M’ of Murder dripping down the page.

The novel centers around a university reunion in a Scottish glen where seven members of the school’s murder mystery society come together to solve one final puzzle. Unsurprisingly, the gathering takes a dark turn when Lady Partridge is found dead, hanging from a pear tree. The dead bodies quickly pile up from there. “You don’t want to know what happens to the French hen,” says Cordani.

As the nights grow colder in the United Kingdom, so does the fiction. “It’s beginning to look a lot like murder…” reads a sign in the Waterstones at Piccadilly Circus, Europe’s largest bookshop. Among the tinsel and holiday decor, titles such as The Mistletoe Murder and Crimson Snow are set out to entice midwinter readers.

These books are classic and modern whodunnit mysteries set during the holidays. In recent years, these murderous tales, littered with poisonous mince pies and corpses inside snowmen, have become more popular than ever, especially in the United Kingdom.

Christmas murder mysteries can be traced back to detective fiction’s golden age between World War I and II. Before World War I, Christmas short stories and detective fiction had been steadily growing in popularity throughout Victorian and Edwardian Britain, eventually developing into the more complicated mysteries of the interwar period.

Agatha Christie published her first novel, The Mysterious Affair at Styles, in 1920 introducing her famed Belgian detective, Hercule Poirot, to the world. In 1938, following criticism that her murders were getting “too refined,” Christie published Hercule Poirot’s Christmas. “You yearned for a ‘good violent murder with lots of blood.’ So this is your special story—written for you,” she wrote in the dedication. In the novel, Poirot is sent to investigate the unceremonious death of Simeon Lee, a tyrannical British millionaire, on Christmas Eve.

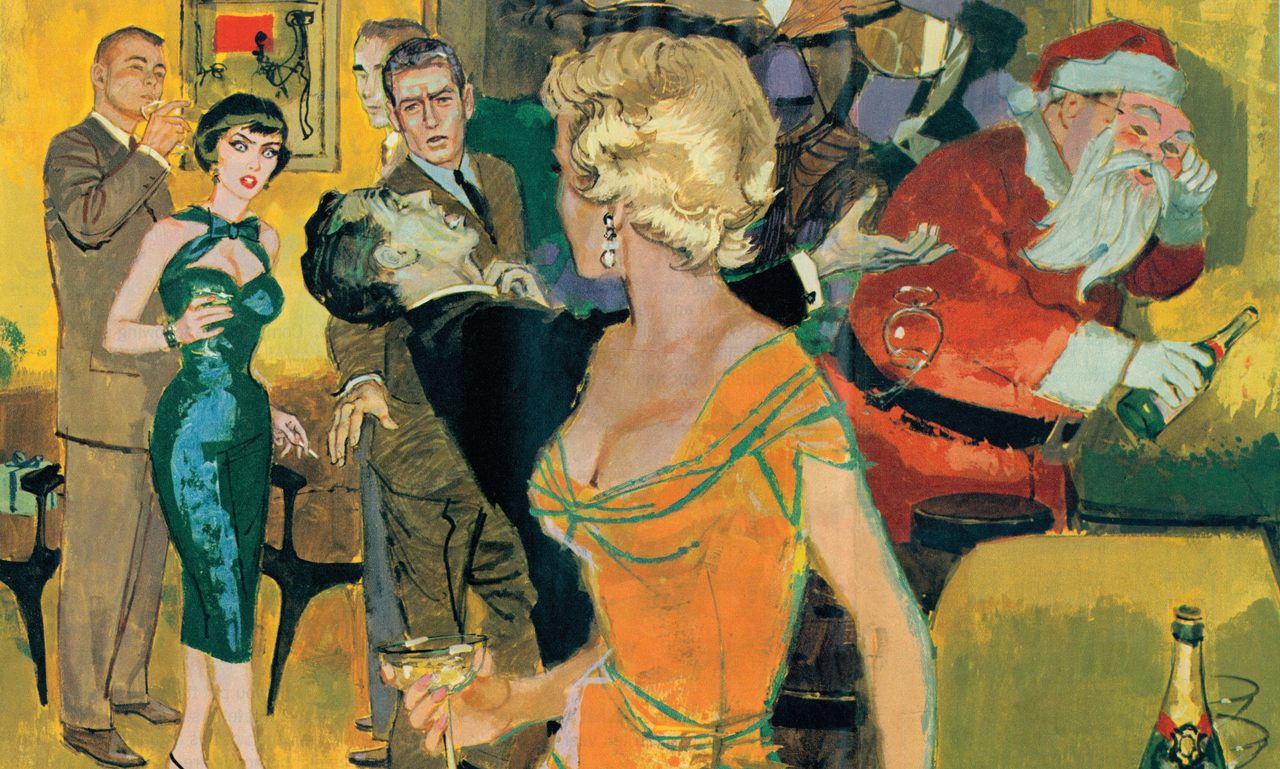

Christie’s holiday murder tale followed The Santa Klaus Murder, published by the lesser-known author Mavis Doriell Hay in 1936. In Hay’s story, Sir Osmond Melbury, a wealthy patriarch, is with his family when a guest dressed as Santa finds him shot dead on Christmas Day.

Homicide and the holidays might seem an incongruous pairing. But golden age crime writing evokes a very festive kind of feeling for some: coziness. These golden age murder mystery novels (and the modern books that follow their style) are now often referred to collectively as “cozy crime” stories.

“It is likely that anxieties following the First World War led to a greater desire for the kind of escapism that crime fiction offers, where readers are greeted with puzzles and thrills in equal measure,” says Jonny Davidson, editor of the British Library’s Crime Classics series, a collection of republished golden age British detective fiction.

Although they are varied and have adapted over the years, archetypical cozy crime mysteries are set in quintessential country houses and are rarely graphic. After an unexpected murder, readers race an eccentric detective or amateur sleuth to decipher clues and find the killer amongst a closed circle of suspects who are known to each other and possibly related—the butler, maid, and gardener excepted. Littered with levity, humor, and relatable characters, the stories culminate in a grand reveal that unmasks the murderer. While some are darker than others, readers sitting safely by their firesides at Christmas can be assured that good (mostly) triumphs over evil.

Between World War I and II, Christie and fellow British writers formed the Detection Club, an exclusive and quirky writers’ group that published its own mysteries. After World War II, the style continued, but some began to stereotype the genre as “twee.” Soon, grittier, psychological thrillers replaced cozy crime stories.

However, in the last decade, cozy crime alongside thrillers has grown more popular than ever, particularly at Christmas. The reason for the revival is open to debate, says Martin Edwards, the author of more than 20 crime fiction novels and the nonfiction book The Golden Age of Murder, which examines the origins of the genre.

Edwards has been tracking down out-of-print and unpublished mysteries for years, working with the British Library to republish them. Christmas murder mysteries have done particularly well in the United Kingdom. “Now you go into a bookshop at Christmas and you can’t move for books with snow and bodies,” he says.

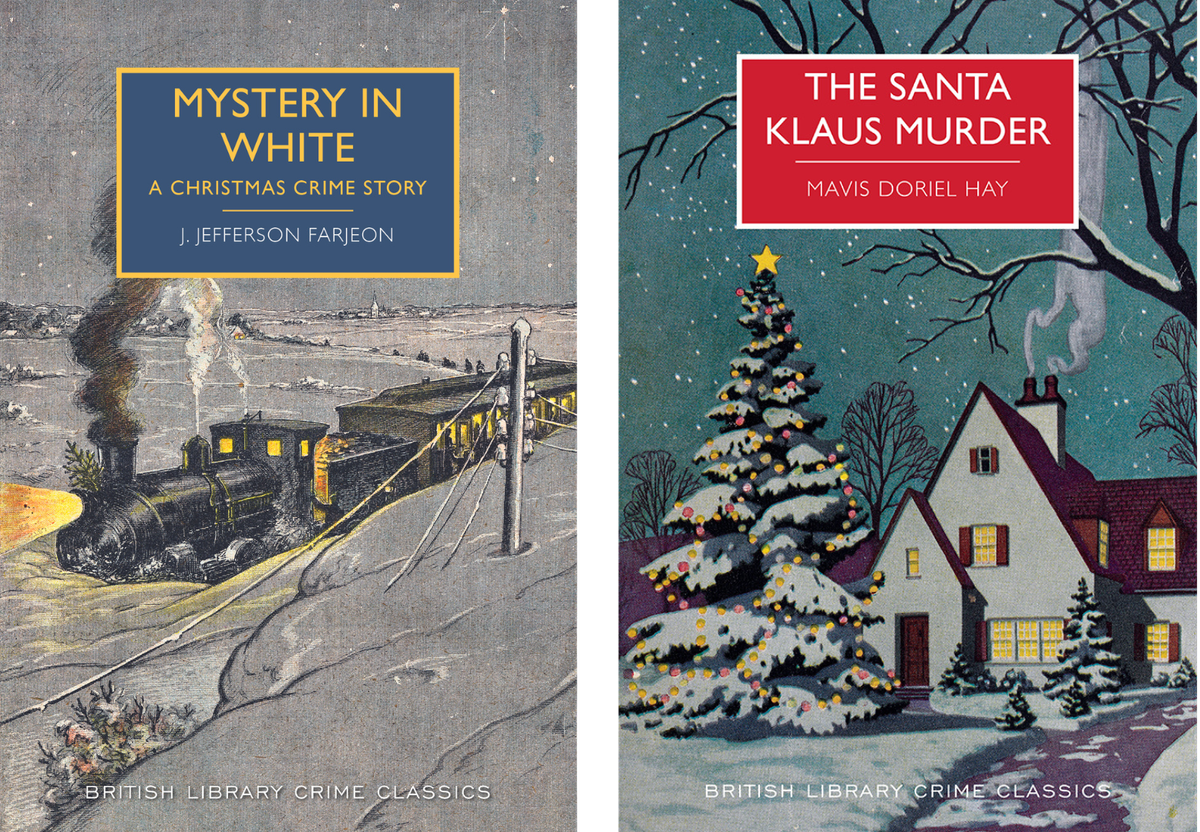

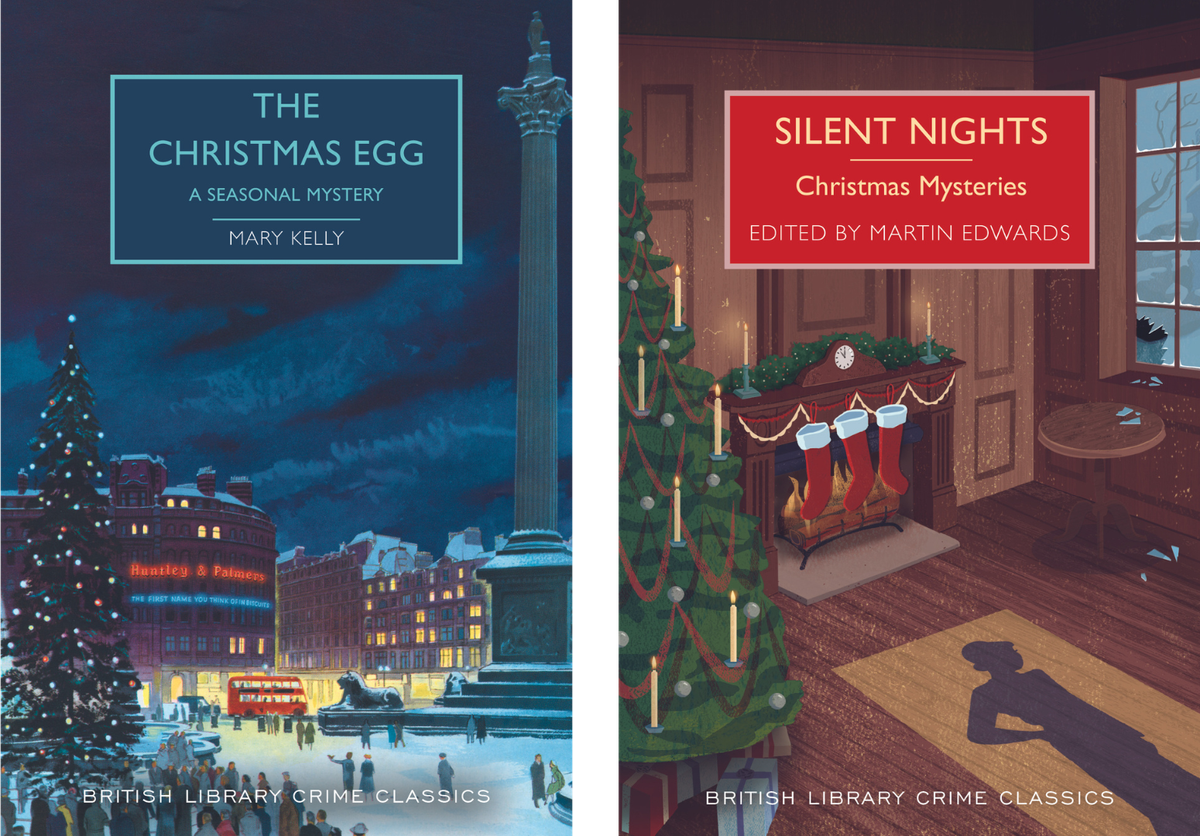

Edwards stresses that the use of atmospheric vintage covers has been key to the republished books’ success. It helps that many of the republished stories are short and easy to binge over the holidays. But they also offer readers an insight into a turbulent time in history, which may feel familiar today.

The original golden age writers were writing about a “very interesting time,” says Edwards, who disputes their coziness, pointing to the genre’s darker works and historical value. “In the 1920s, it was a reaction to the horrors of the First World War. In the 30s, there’s the economic slump and economic tensions,” he says. “Is it that life today seems weirdly reminiscent of life in the 30s with all [its] uncertainties?”

When the British Library republished J. Jefferson Farjeon’s Mystery in White: A Christmas Crime Story in 2014, it became a bestseller. From then on the library and Edwards have brought out Christmas crime novels and anthologies of republished mysteries with fearfully festive names. This year it’s Who Killed Father Christmas and Other Seasonal Mysteries, including a 1980s murder mystery where Santa is murdered in a busy London toyshop.

The intellectual challenge of cozy crime makes the genre particularly attractive to readers at Christmas. For Simon Lee, a law professor at Aston University who moonlights as a murder mystery writer, the stories are about “fact-finding and how to deal with conflicting evidence,” he says. “At one level, you’re reading it for enjoyment, and at another, you’re seeing if you can solve [the mystery] before the writer tells you the answer.”

Lee, who published his own festive whodunnit, The First Lockdown Christmas Mystery, thinks the holiday season is the perfect setting for a murder mystery and has encouraged his law students to write their own death-dealing tales over winter break.

At Christmas, there are plenty of traditions to play on and it’s easy to imagine a group of people stuck inside for long periods, possibly snowed in. As tensions (and spirits) rise, a cozy crime setup may start to feel familiar. “The nearest most of us come to that is at Christmas,” he says. “For good or ill, you end up with extended family and you often feel like killing them.”

These days not all Christmas murders take place in quaint English villages—and not all authors or characters are white and middle class, a common criticism of the genre. “Crime fiction, like most of the publishing industry frankly, was dominated for a century or more by middle-class, white, and largely male writers, with the exception of several very prominent golden age crime writers like Agatha Christie and Dorothy L. Sayers,” says Vaseem Khan, author and chair of the Crime Writers’ Association, which supports authors and hosts awards and events. Khan, who is the first person of color to chair the CWA, sets his murder mystery series in modern and historical India and his short stories involve one of his favorite Christmas themes—killing off Santa.

The current popularity of crime fiction cuts across countries, continents, and cultures, he says, with the industry making efforts to match readers’ demands for more diversity. “I’ve seen a genuine and concerted attempt by most actors across the publishing industry—that means agents, editors, publishers and marketers, bloggers, event organizers—to move that dial.” His latest Christmas murder mystery, A Yuletide Murder in Old Bombay, will be published in a U.K. newspaper in three parts in late December 2023.

Like Professor Lee, Khan finds that the best Christmas murder mysteries offer a challenge and are thought-provoking. But they’re also based on the reality of family holidays. “You’ve got these seething things going on under the surface,” he says. “Crime fiction takes that one step further: You bump someone off. Normally, we’ll just have a fight at Christmas, a sulk, and not speak to each other for a year.”

At their heart, Christmas murder mysteries are morality tales, he says. Using the holidays and an endearing detective to highlight the good and bad in human nature as we head toward a new year.

Writing cozy crime mysteries, including those set in the holidays, has become so popular in recent years that Khan along with the rest of the Crime Writers’ Association has introduced the Whodunnit Dagger, an award for cozy crime stories. According to the CWA’s website, the award goes to a tale that has a clever, “intellectual challenge at the heart of a good mystery, and revolve[s] around quirky characters.” The CWA’s Twisted Dagger award for psychological and suspense thrillers has launched as well, reflecting the two biggest-selling crime genres today.

The popularity of murder mysteries has also made its way to the screen. In the United Kingdom, it just wouldn’t be Christmas without an Agatha Christie adaptation. This year, it’s the two-part Murder Is Easy, which will hit screens on December 27th.

Also across the nation, hotels, restaurants, and even castles are booked out for Christmas-themed murder mystery events in high numbers. Sometimes Sam Emmerson is the one renting them out.

Emmerson is the creative director of Moonstone Murder Mysteries, a murder mystery events company. He writes the scripts, runs the shows, and hires actors to entertain guests who play detectives for the evening.

“We’ve lost a dead body before,” he says, recalling a performance where an actor playing the victim misheard a direction, leading 100 guests to scour a hotel only to find him lying in the grass outside.

Emmerson’s company offers two Christmas mysteries. Murder by the Mistletoe is set at a 1920s coaching inn and Winter Wonderland, their best-seller, takes place in a modern-day garden center grotto where Mrs. Claus has been found with a string of Christmas lights around her neck.

“Christmas is huge because of Christmas parties. We’ve got God knows how many Winter Wonderlands going out this year,” he says.

For crime author Cordani, the tongue-in-cheek humor of Christmas murder mysteries isn’t just about laughs—it’s critical to the genre. “The whole point of the midwinter holiday is to remind us that there is still light,” she says. Even as the bodies pile up in Cordani’s The 12 Days of Murder, there’s still a lightheartedness to the story reminding readers that “the good days will come back.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook