Make a Historic Boston Dessert That Became a Japanese Favorite

Unless you make it yourself, coffee jelly can be hard to find stateside.

In 2019, a Boston restaurant closed. Normally, a restaurant closing in a major city wouldn’t cause much of a commotion, but this was different. Durgin-Park had been open for almost 200 years, and was famed for serving what food historian Paul Freedman calls the “first forgotten cuisine” of the United States.

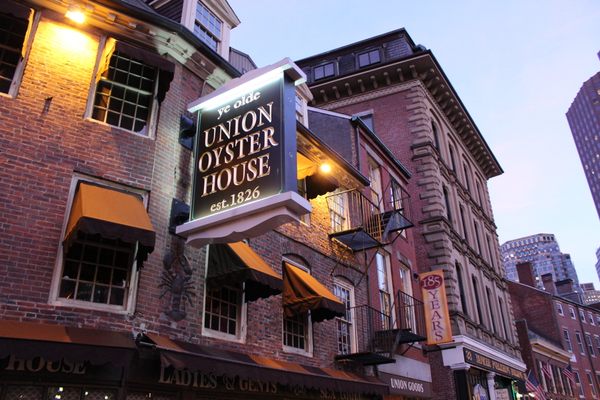

Durgin-Park, located in Boston’s Faneuil Hall market, was truly the last of its kind. Something of a tourist trap in its later years, the restaurant slung crock after crock of Boston baked beans (once the city’s calling card) as well as crowd-pleasing fare like pasta and onion rings. But it also sold bygone historic New England favorites, like “Indian pudding” (a cornmeal-and-milk treat created by early colonists) and a now nearly extinct dessert: coffee jelly.

Coffee jelly might seem like nouvelle cuisine of the highest order, seeing as most of us are used to having our coffee as a liquid rather than a solid. But it’s actually the opposite. Early recipes for coffee jelly are at least as old as Durgin-Park. One recipe, from an 1836 issue of New York’s Lady’s Book magazine, told readers to mix coffee with the gelatin produced by boiling a calf’s foot. With cream and sugar, it became an elegant dessert. Gelatin, for much of the 19th century, was a luxury, requiring boiled animal parts and a cool enough spot to allow it to set. A platter of shimmering coffee jelly, turned out of a decorated mold and served with a cream sauce, would have elicited oohs and ahs at a tea or dinner party.

As the 19th century turned into the 20th, jellies became much more egalitarian. In fact, gelatin in general became a huge trend, says Megan Elias, a food historian who studies American cuisine and home economics at Boston University. “Jellies became popular when powdered gelatin entered the market but even more popular when electric refrigerators enabled people to keep their jellies cool,” she says. Gelatin, including the coffee-flavored variety, even gained a reputation for being especially good food for the sick. At one point, the English medical journal The Lancet even recommended coffee jelly as an after-dinner antidote to too much alcohol.

But it seemed to be especially popular in Boston, considering the flurry of recipes requested and printed in the city’s newspapers around the turn of the century, often packaged as one of the favorite recipes of “The Women of New England.” With its easy-to-find ingredients and short recipe (mix brewed coffee with dissolved gelatin and sugar, and serve with some kind of milky sauce), it embodied a certain Yankee ideal of simplicity, or even frugality, if using leftover coffee.

And no one promoted that ideal more than Fannie Farmer. A tough businesswoman who reportedly wasn’t all that interested in food or cooking itself, Farmer nonetheless became a culinary star, with cookbooks and columns promoting the hearty, heavy food that she considered the ideal fuel for most Americans. Her regularly-reprinted Fannie Farmer cookbook, though, contained an entire section on delicate jellies, many infused with fruit juices and liqueurs. Coffee jelly is there, too, served with sugar and cream, and Farmer’s columns over the next few decades recommended the jelly as a dessert, alongside other New England specialties such as Boston baked beans and summer squash.

In Freedman’s book American Cuisine: And How It Got This Way, he notes that home economists such as Fannie Farmer “wanted Americans to adopt New England cooking.” Specifically, they wanted Americans to eat food that recalled the colonial American era, which had become a national obsession due to the 1876 centennial. Thus, old local foods such as baked beans and Indian pudding, which smacked of “the frugal ideal of the early American republic,” suddenly gained a new shine, one that lasted well into the 20th century. This shine also applied to restaurants such as Durgin-Park, which made coffee jelly with their leftover brew. Elias notes, though, that coffee jelly wasn’t usually just a way to use up old coffee. “Since the first Jell-O powders required hot liquids, the coffee used would not have been leftover,” she writes in an email. “Also coffee isn’t the kind of thing that people usually have leftovers of—we drink it up.”

New Englanders didn’t prove lastingly enthusiastic about coffee jelly. Gelatin, once so rare and prized, was ubiquitous in the United States by the 1950s. Inevitably, the elegant jellies of yesteryear became hopelessly gauche. Some passionate fans of coffee jelly, such as Roger Berkowitz, the CEO of Boston’s Legal Sea Foods, fought for the dish, even putting it on the restaurant’s menu as recently as 2016. But this lasted only for a short time. When Durgin-Park, after years of declining revenues, finally closed in 2019, the dessert slipped even further into obscurity, like coffee jelly from a spoon.

At least, that’s what happened in the United States. Coffee jelly lives on in Japan. In fact, it’s so popular in the country that it’s often considered to have been invented there. But one theory is that a Japanese journalist who studied home economics in the United States published a coffee jelly recipe in 1914 after returning home. Coffee jelly wouldn’t achieve major popularity in Japan until the 1960s, after the Mikado coffee shop chain began dishing it out. It rapidly became a classic, served up with milk or whipped cream, sometimes cubed into glittering chestnut-colored cubes. Today, it’s sold in corner stores and sweet shops around the country. In fact, even Starbucks got into the coffee jelly scene in 2016, releasing a coffee jelly–filled Frappuccino.

Similarly, coffee jelly has returned to the United States in one format, as one of many garnishes for the drinks served up in bubble tea shops. At the moment, it doesn’t seem like anyone’s clamoring for the return of cool, slippery, slightly bitter gelatin to Boston’s dessert menus. However, coffee jelly is so easy and inexpensive to make that perhaps it’s best enjoyed at home. Fannie Farmer would approve.

Coffee Jelly

Makes five half-cup servings

Ingredients

One .25-ounce envelope of plain powdered gelatin, such as Knox

1/2 cup cold water

2 cups hot coffee, either fresh or heated up

⅓ cup sugar

Whipped cream or sweetened condensed milk, for serving

Instructions

1. In a heat-safe bowl, add the powdered gelatin to the cold water, and let it sit for a minute or two. Then, mix until the grainy liquid is mostly smooth.

2. Add the coffee and stir, ensuring that the gelatin granules all dissolve. Then, mix in the sugar, again making sure that it dissolves completely.

3. Divide the mixture into five small ramekins, or even teacups. Put them in the fridge to set, for at least two hours.

4. Serve the coffee jelly with whipped cream or a healthy drizzle of sweetened condensed milk.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook