The designer Louise Harpman and the architect Scott Specht are both coffee connoisseurs, but not in the way you might expect. They’re not as much enamored by the beverage as they are by what prevents it from spilling: the coffee cup lid. Together, they own the world’s largest collection of disposable coffee lids.

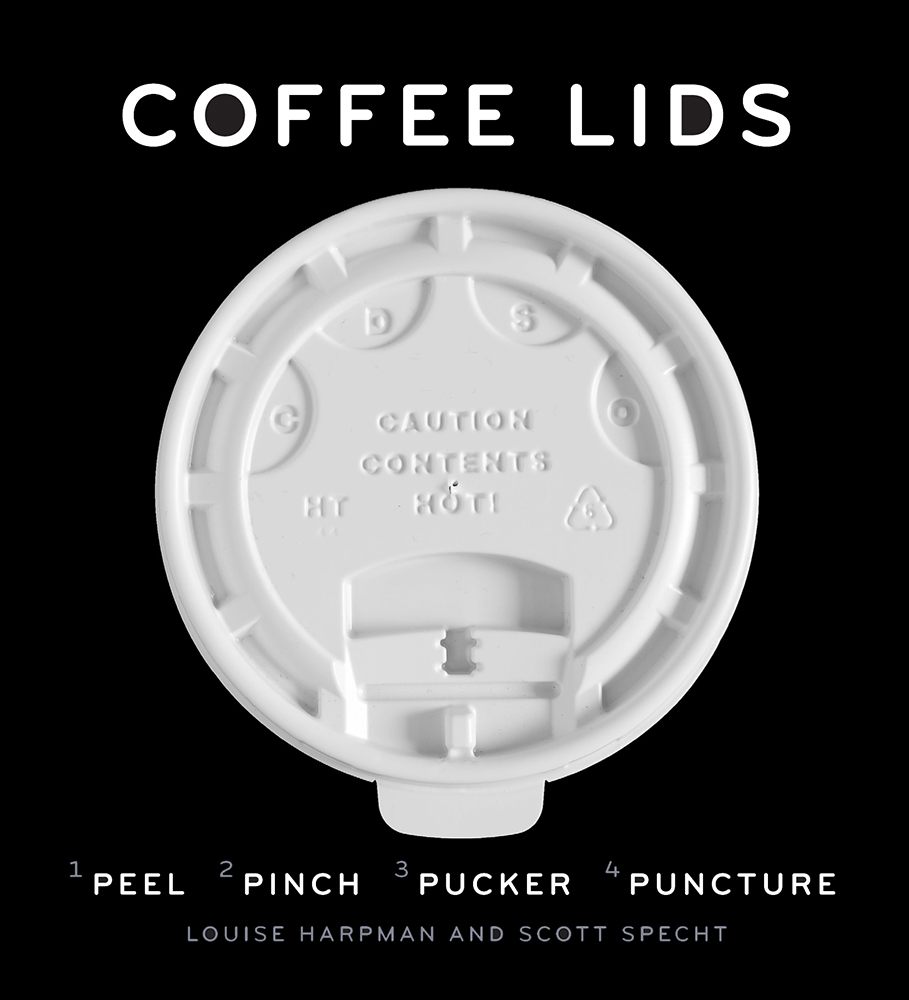

The coffee cup lid is one of those seemingly mundane inventions that are so fully integrated into modern life, they’re easy to overlook. But as Harpman details in the introduction to the new book she co-wrote with Specht, Coffee Lids: Peel, Pinch, Pucker, Puncture, there is a fascinating design history behind the objects.

In the mid-20th century, as the popularity of drive-ins and fast food restaurants increased, customers with a hot to-go beverage had a problem: they couldn’t access their drink through the lid. And so, Harpman writes, these coffee lovers became “accidental DIY designers: they created the first drink-through coffee lids by peeling way small sections of the flat polystyrene, thermoformed lids.”

Since then, designers have created a wide array of coffee lid styles to address this one simple problem. For their collection, Harpman and Specht put together a taxonomy of the lids, which is based on how the liquid is accessed by the drinker—peel, pinch, pucker, and puncture. These features, Specht writes in a chapter titled “A Brief Field Guide to the Coffee Lid,” can be appreciated in the book and “when observing lids in the wild.”

Atlas Obscura caught up with Harpman and Spect about their new book, the evolution of lid designs, and what the future holds for the coffee cup lid.

Why did you start collecting coffee cup lids?

Louise Harpman: Drink-through plastic coffee lids began to populate the urban landscape in North America in the early 1980s when I was in college. Taking coffee “to go” became a common activity, and that’s when I began noticing that different coffee shops used different lids. When I noticed a new lid, I would get one, whether or not I was buying a coffee from that particular shop. The fascination was—and still is—watching how behavior and design were so intimately linked.

Scott Specht: I never initially saw myself a collector—I did love to accumulate random, often ephemeral items that I found to be beautiful (and that were literally found—in dumpsters, old factories, etc.) I did begin to notice, however, that I was accumulating more coffee lids than other items, and began to appreciate the often over-the-top attempts to engineer a solution to the problem of “coffee slosh.” This led to a curiosity about why there is such a profusion of lid types. This also led to many acid-free portfolio boxes full of lids stashed under the bed.

I’ve also always been fascinated with “design bubbles”—brief periods of time in which an object or product undergoes a rapid evolutionary profusion. Toothbrushes followed a similar arc, from simple commodity that was formally the same despite manufacturer, to today’s range of endless variations with different grips, bristle types, degrees of mechanization, etc. As our collection increased, I could see the evidence of a similar phenomenon taking place with coffee lids.

Tell me a little bit about the taxonomy you’ve used to categorize the lids, and how it originated.

LH: If a group of things aspires to be a collection, there has to be some kind of legible ordering principle…to make sense of them, to group “like with like.”

SS: The categories (roughly) follow the chronological development of the lids. The first drink lids were homemade hacks made to simple, flat lids—people would just tear a ragged wedge from the side and hope for the best. This led to the first “peel” lids, in which the tearing process was aided by perforations as well as indentations to lock the resultant tab in place. Then, in the 1980s a profusion of specifically designed “drink lids” attempted to improve the experience. This “golden age” produced some often ungainly solutions such as the “pinch” and “puncture” variants that are now rare. Currently, the “pucker” lid—in which a higher dome, ergonomic lip, oval slot, and inexpensive one-piece design has become the standard.

What do you think is the next evolutionary step for the coffee cup lid?

LH: Lid design has certainly changed with the introduction of so many foamy drinks. The lids with additional “loft space” are meant to accommodate the latte lovers and whipped cream connoisseurs of the world. The other trend focuses on the introduction of new materials. We start to see more compostable plastics (which should be the norm, not the exception), and thermochromic plastic which changes color relative to the heat of the drink.

SS: Of course, the lid of the future will incorporate web connectivity and photovoltaic power sources… We are now seeing the arrival of many lids that are sculpted into decorative forms such as faces, lids that can change color as with the thermochromic lids, and lids that “plus” the drinking experience with enhanced aroma concentration.

What are your hopes in sharing this collection with the world?

LH: I want people to experience the fundamental and deeply satisfying pleasure of looking. Just looking at the things that surround us. Coffee lids are modest modern marvels, but we rarely slow down and take the time to consider, admire, or even wonder about these humble masterpieces.

SS: There is a basic aesthetic pleasure in simply seeing a presentation of similar, but not identical objects. It can also inspire deep curiosity—trying to figure out why the objects differ, and what forces produced those differences. Our collection started with a shared interest in one common, overlooked object. It led into a fascinating subculture of designers trying to solve a problem, often in bizarre and seemingly counterintuitive ways. There is a story in these lids, and I think it is a narrative worth sharing.

Do you have a favorite from the collection?

LH: Just one favorite? Impossible! They all have their own personalities.

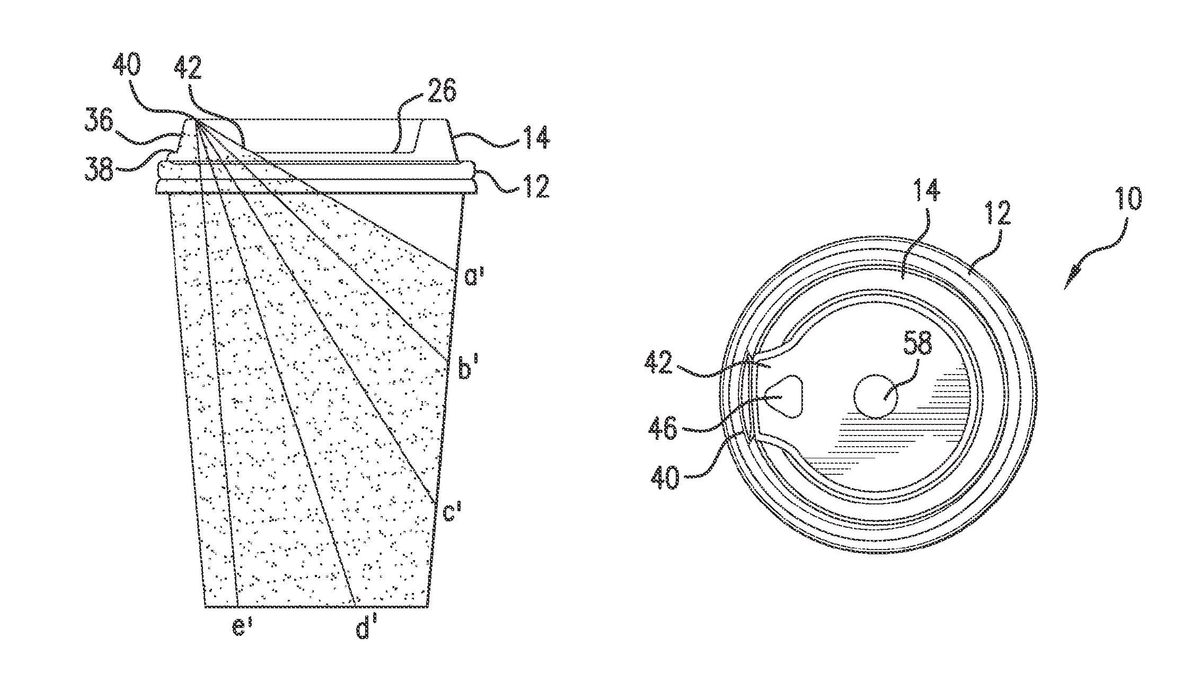

SS: My favorites always exhibit some element of overwrought madness. The Philip Lid is a great example. It not only has a complicated design with a system of internal vents and reinforcement channels, but it could only be used with the accompanying patented Philip Cup (styrofoam only!). Needless to say, this evolutionary dead-end didn’t entice too many coffee shop owners to buy.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook