The Rise and Fall of the Mormon King of Beaver Island

Rumors of piracy, polygamy, and betrayal shape the tumultuous history of King James Jesse Strang.

In the northern reaches of Lake Michigan, the Emerald Isle ferry—departing from Charlevoix at the northern tip of the Lower Peninsula—takes about two hours to reach the lake’s largest island. As it approaches, homes, a lighthouse, and a red-roofed research center pop into focus amid dense forest. Docked boats herald the ferry with honks, and dogs bark from ship to shore. Upon arrival on Beaver Island, a lively community center and welcoming crowd beckon family and visitors ashore. On the island it’s customary to wave, or at least lift a finger, for each passing vehicle—every single one.

“When it’s just us, if someone doesn’t wave to you it’s like, ‘Wow, what’s that all about?’” says generational islander Garrett Cole, in a perfectly worn flannel, with a long white ponytail down his back.

It’s the week of the normally sleepy island’s summer music festival. There are only about 600 year-round residents, and the festival brings more than twice that to the wooded grounds in the middle of the island, where local vendors set up near three side-by-side stages. “What do you call people from Beaver Island?” a musician calls out from the left stage. “Lucky!” someone in the crowd shouts back. “Prisoners of paradise” is another answer sometimes offered.

Amid the sunny days and summer fun, there are hints of another, darker past: a few historical markers between clover-lined fences, and a name that appears repeatedly on a main road, a hotel, and the township itself: St. James. All are named after James Jesse Strang, the self-appointed Mormon king of Beaver Island.

In 1847, the island was only home to a couple hundred people: members of several Anishinaabeg tribes who seem to have had a long history on the archipelago, as well as some Irish immigrants who had arrived a decade or so earlier. Fur trapping, fishing, and lumber were the industries of the island, which was tied to the nearby economic powerhouse of the Great Lakes, Mackinac Island, and its lucrative whiskey trade.

Suddenly, the island found itself host to an outsized figure in Strang, who arrived with a small group of followers that year. By 1850, Strang had declared himself “king.” Over the ensuing few years he attracted some 2,500 followers to this remote place. They farmed and built—and developed a notorious reputation: “one of the most desperate bands of pirates that ever infested American waters,” according to an article in The New York Times, published 60 years later. Strang’s “kingdom” lasted only six years, and disappeared just as quickly—and dramatically—as it had arrived. But the legacy of the pirate Mormon king of Beaver Island is far from settled.

“It’s fascinating, the juxtaposition between reality and folklore,” says Mormon historian and present-day follower of Strang, John Hajicek, who has been researching Strang for nearly 50 years. “It’s really about the story of the story.”

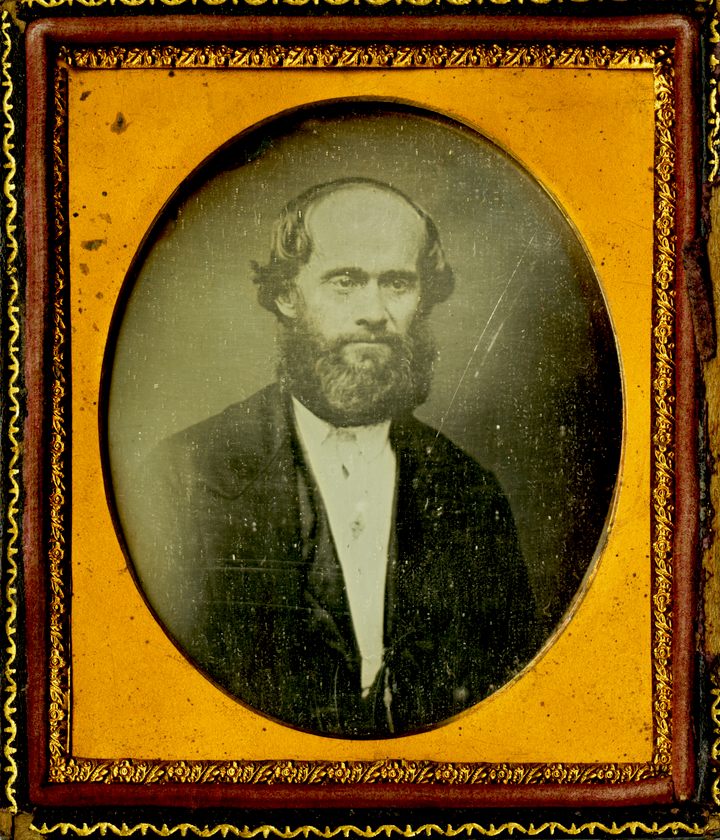

Friends, foes, and fans all agree that Strang was intelligent and ambitious. In 1846, the New York Tribune described him as “rather below the ordinary size and very plainly dressed…. In fact, I may as easily describe him by saying he is a diminutive, ill-favored, insignificant looking man.” But, the text adds, he “possesses considerable talent.”

Strang was born in Scipio, New York, in 1813, and worked variously as a lawyer, newspaper editor, and Baptist minister. In 1844, he left his faith to join the congregation that had recently been renamed the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, based at the time in Illinois, having been founded in 1830 by Joseph Smith, author of the Book of Mormon. When Smith was killed later that year, near the Mormon stronghold of Nauvoo, Strang was one of several men who stepped forward to take his place. Strang even presented a letter of questionable authenticity addressed from Smith declaring him as successor. Brigham Young rivaled Strang, and set his sights on moving the congregation to Salt Lake City, Utah, where he ultimately took the majority of the people who would also come to be known as the Latter Day Saints. Strang looked north, and took a smaller group of followers to Voree, Wisconsin. He opposed polygamy (at least for a while), in contrast to Young and others, which gained him many followers. He claimed an angel guided him to his own set of brass plates, not unlike the set that Smith said he found and interpreted into the Book of Mormon.

One night, another angel came to Strang in a dream and showed him “a land amidst wide waters and covered with large timber,” he wrote in one of his revelations. This took him and a handful of followers to Beaver Island, much to the consternation of the Anishinaabeg and Irish communities that were already there. Over the next couple years he would draw more and more followers to the island. In a short time, they built roads, homes, and farms that still shape the island today.

“I’m amazed by what they did,” says the islander Cole. “They built these roads, they cleared land, and they built all the farms. They worked like mad. They did it all in 10 years. I just can’t get over that.”

On July 8, 1850, James Jesse Strang crowned himself the “King of the Kingdom of God on Earth.” There are a few different versions of the scene, but most include a ceremony, complete with a crown, robe, scepter, and painted backdrop. As king, Strang pushed Irish and Native American children into Mormon schools (a failed effort). Allegedly, he gathered the incumbent islanders and told them they could convert or leave. By 1852, almost all non-Mormons had chosen the latter option.

Though the island might seem remote, it was in a strategic location, which contributed to Strang’s growing economic and political influence. He was elected to the Michigan legislature twice, and was gaining sway throughout the region. This brought Strang yet more enemies, including the U.S. government. He had been accused of treason and other crimes, which he evaded in court, at least for a while.

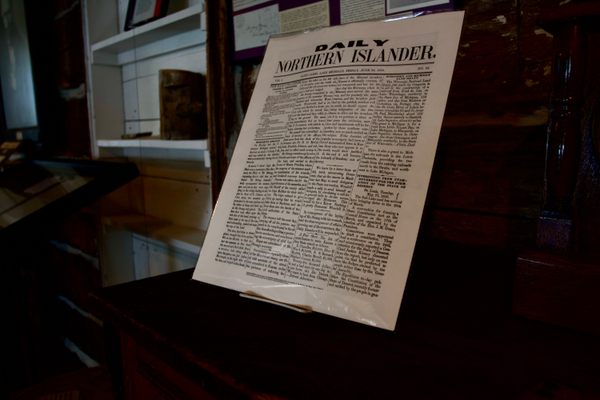

As they were building, the followers of the king were also busy spreading the word. Strang established the first newspaper in northern Michigan in 1850, The Northern Islander. His efforts were more than local. “They’d run ads around the world, come to Beaver Island, we’ll give you 40 acres and $100,” says Henry Granger, an avid visitor to the island, and author of deeply researched historical fiction about Strang.

In 1855, newspapers from Michigan to New York began to run stories about “a gang of marauders” or “pirates” plaguing Lake Michigan. The gang burned sawmills and stole goods, which they displayed on their ships. They carried out “their operations with a boldness, coolness and desperation rarely equalled in the records of highwaysmen,” according to an 1855 article from The Hillsdale Standard, published in southern Michigan.

“There seems to be no question as to the identity of robbers, or their hailing place,” the story continued. “They are emissaries from King Strang’s realms.”

More tales followed. Strang and his followers were settled with responsibility for luring ships ashore to board and plunder, stealing horses, and destroying nets in areas where fishing was big business.

Many of these tales of Strangite piracy have been dismissed over the years, and they’re little part of the lore told on the island today. Cynthia Prior, a historian for the local lighthouses on Beaver Island, says she’s never heard of that side of Strang. “That’s all folklore,” says the Mormon historian Hajicek. He says it was a twisting of real events, when a ship washed ashore and the Mormons salvaged the wheat aboard.

He believes the Mormons became an easy target when anything went wrong. “You wouldn’t write a story today and say, ‘We now know the facts, I checked out the New York Tribune from those days, and yep they were called pirates, so they’re definitely pirates,’” he says. “You don’t just blame all the crime from an entire state on one tiny, tiny group, just because they’re culturally different from you. But that’s what we’re doing. And that’s what they were doing already back then.”

Granger believes that piracy was an issue in the region, but doesn’t claim to know the culprit. “I think it was done,” he says. “It wasn’t necessarily Mormons.” He agrees that the Mormons became an easy scapegoat, as they were already widely distrusted.

Other dark stories of Strang and his policies and behavior have persisted in the historical record: ruthless whippings, firing a cannon into a crowd of Irish on the island, animal sacrifice rituals, and stealing the wives of his followers after reversing his original anti-polygamy stance.

These stories are tied up with the legend of his death. In 1856, the captain of USS Michigan invited Strang to dinner on his ship. As Strang stepped onto the dock, two of his own men ambushed him from behind a stack of wood. Some say the men were manipulated into shooting him, others that it was revenge for wife-stealing. Allegedly, one of the men to shoot Strang had been whipped in public for his wife’s sartorial choices, according to the island’s museum.

After he was shot, Strang was whisked away to Wisconsin, where he died two weeks later. His remaining followers on the island soon drew the attention of an angry mob from around the region. They burned his house and documents, and chased the Strangites out.

Most retreated to Wisconsin. Hajicek is one of what he guesses to be around 100 devout followers of Strang today, joined by 500 other members and thousands of what he calls “fans” in the historical community. Occasionally, Cole has even met a few Mormons visiting the island. “I suspect there may have been more than that,” he says. “We just don’t know about them.” And he doesn’t think anyone on the island holds animosity toward them today.

“If you take Mr. Strang out of the equation—if it was just his people—things would have been so different,” says Cole. “But Strang just turned into kind of a radical,” adds his brother, Paul Cole.

Today Strang carries a villainous reputation—declaring yourself a tyrant and acting like it tend to have that effect—but some still see him as a saint, and blame time for twisting the tales. Amid the dark stories, Strang had some rather progressive thoughts, says Hajicek. He was an abolitionist, ordained women and people of color to the priesthood, and practiced environmentalism, he explains.

“There probably is no absolutely true story of him,” says Granger. “Either he’s presented as this poor misunderstood theologian, which he wasn’t, or somebody will present him as this horrible polygamous asshole that tried to copulate with every female on the island, which was probably somewhat true.”

The Cole brothers are more interested in the Native American history of the island than they are its most notorious resident. “They’re the real Islanders,” they agree. Garrett, as well as Prior and a few of the island’s Indigenous residents, are part of the Amik Circle Society, which seeks to understand, and more importantly protect, the physical history of the present tribes and “the ancient ones,” with a legacy going back thousands of years.

The island’s history remains shrouded in lore, but that doesn’t mean it’s not worth exploration. After Strang’s death, no one wrote much about him until 1882, nearly a quarter of a century later. It was those tales that seem to have cemented, or at least strongly colored, his legacy. Fair or not, history remembers Strang as a despotic pirate. “The stories that the authors choose frame the conversation forever after that, we see the same thing in other American history subjects,” Hajicek says. On this unsuspecting island in northern Michigan, the complicated truths of the past are pieced together through legend, lore, literature, and modern hearsay.

“From a history standpoint, if people are traveling and they want to study a fairly fresh example of how history morphs,” says Granger, “this is a great place. From a travel standpoint, it’s just beautiful—the whole island experience.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook