Decoding the Classic Burglar Outfit

Where did the crook in the striped shirt come from?

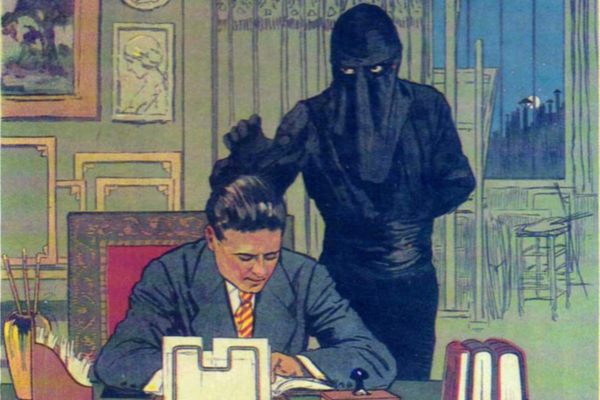

Here he comes, creeping through a shadowy alley. It looks like he’s getting away, until a police spotlight captures him against a stark brick wall. In a black domino mask, striped shirt, flat cap, and holding a sack of purloined goods, it’s a BURGLAR!

We can all see the stereotype in our mind’s eye, but where did this cartoonish image come from? The very first instance of the stereotypical burglar is a bit unclear, but the various elements of the figure can be found springing up around the 1800s, though the roots of some costume elements go back even further.

The oldest element of the villainous caricature is the domino mask, which can be traced back to the masquerades of the 17th century. In Venice during the 1600s, elaborate costume balls allowed their mainly upper-class attendees to don masks to obscure their identities so they could be removed from the rigid expectations of their social class. This encouraged an air of clandestine intrigue that is still associated with carnival masks.

Many of the traditional masks of the time were elaborate, full-face masks, but the smaller half-masks, which only covered the eyes and sometimes the nose, were also a popular option, for both men and women. Also in the 17th century, the trickster character of the harlequin came into prominence, and was most often depicted wearing a smaller domino mask, which only surrounded the eyes.

As the tradition of the masquerade spread throughout Europe, the mask eventually became simplified into a black strip that laid across the eyes, with holes cut out so that the wearer could still see. This basic mask, whether directly descended from the world of the masquerade or created simply out of necessity, became associated with ne’er-do-wells who wanted to hide their identity. Depictions of a burglar wearing a simple domino mask can be found as early as 1871, in an advertisement encouraging women to arm themselves for home self-defense. Although the figure in this advertisement is wearing a suit as opposed to the striped outfit that would become more iconic, the early seeds of the trope are plain to see.

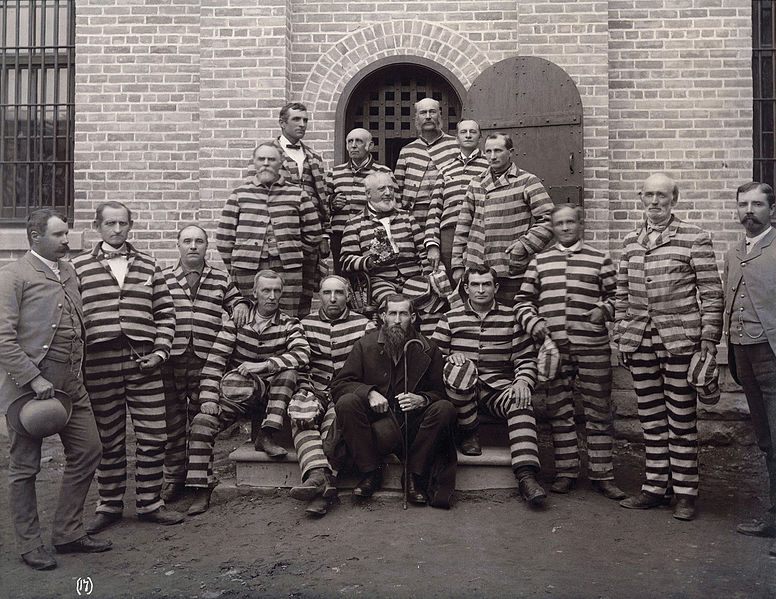

Speaking of that striped shirt, they too came from the 1800s. The striped burglar’s shirt was originally inspired by the striped, duotone uniform of prison inmates. The striped uniform was introduced as part of what we now call the “Auburn System” of penal management, which began being practiced around 1820. Under this system, prisoners were largely kept in solitary confinement, and made to perform hard labor in complete silence. The uniforms introduced with this system consisted of shirts and pants in matching, horizontal black-and-white/gray stripes, and were meant to make the inmates instantly recognizable, much like some brightly colored prison uniforms do today. The zebra-stripe style of inmate uniform spread throughout the New York penal system to prisons like Sing Sing, and across much of the rest of the country.

It wasn’t until the turn of the century that views surrounding prison uniforms began to shift away from the stripes, towards a more basic style that would not stigmatize the incarcerated laborers quite so immediately (though it’s worth noting that some modern correctional facilities have gone back to dressing inmates in stripes). However, after nearly a century of criminals wearing such a distinctive pattern, the damage was done, and images of criminals in stripes had become part of the cultural lexicon, appearing in photos and political cartoons.

Once the pattern was synonymous with criminality, it wasn’t a huge leap to having a cartoonish burglar wear the stripes. It’s a bit ironic that the stripes real convicts were made to wear so they could be identified would come to represent burglars in the middle of a crime.

Then there is the sack of loot these cartoon crooks are so often seen absconding with, which would also seem to originate in the 1800s, but is probably not rooted in much reality. The origin of the burglar’s bag, which in depictions from the U.K. often bears the word “swag” (yes, pretty much like we would use it today when referring to free promotional items), or in the U.S. with a more universal dollar symbol, leads back to a satirical children’s lyric called Burglar Bill. In this 1888 poem, a burglar breaks into a house and runs into a precocious young girl who convinces him not to rob their house, sending him into a repentant reverie. One early line in the poem, describing the robber entering the home goes:

He is furnished with a “jemmy,”

Centre-bit, and carpet-bag,

For the latter “comes in handy,”

So he says, “to stow the swag.”

While the tools are a bit archaic (a “jemmy” would be akin to a crowbar, and although a “centre bit” is a bit of a mystery, it is described in one reference from 1889 as a “spinner”), the swag bag is easily recognizable as the inspiration for the burglar’s bag.

On its own, each element of the iconic burglar image has its roots in image of criminal life, but it’s hard to pin down the first time they were all brought together. Silent film expert Fritzi Kramer, creator of the Movies Silently blog, isn’t aware of any instances of the trope appearing in early silent films, although she does point out another key element of the figure: his hat.

“I’m afraid I’ve never seen the burglar outfit in a silent film,” she says. “The cloth cap was quite common but that was standard working class headgear for both men and women. Also, five o’clock shadows were quite the thing.” This flat cap has been a common bit of headgear for centuries, but it is now often found adorning depictions of crooks and criminals, almost more often than the striped top. In many modern depictions, the flat cap is sometimes replaced with a beanie.

A likely culprit for creating the iconic burglar image may actually be a children’s book from the 1970s, loosely based on the aforementioned poem, Burglar Bill. Released in 1977, this Burglar Bill was a children’s book by Allan Ahlberg and Janet Ahlberg, and focused on the titular character as he finds a baby and reforms his ways. In the book, the titular figure is illustrated wearing each element of the classic outfit: the domino mask, the striped shirt, the loot bag, and even the cloth flat cap. When he meets another burglar, she too is wearing the domino mask and striped shirt, instantly recognizable as a burglar.

Today, classic elements of the burglar’s look can still be seen in places ranging from the Beagle Boys of DuckTales fame, in their domino masks and flat caps, to the Hamburglar in his striped suit. Actual depictions of the cartoon villain combining all of these iconic elements are rarer since the figure is by its very nature generic, but that low brow criminal figure is still skulking around the collective consciousness.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook