Investigating the Cold-Blooded Murder of a Long-Dead Dodo

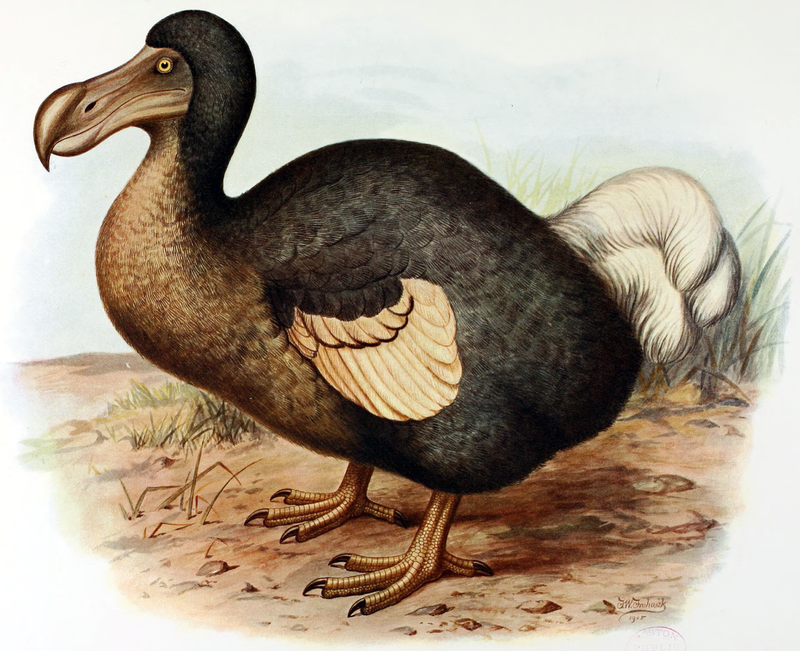

Who killed the flightless bird at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History?

If you want to see a dodo, your best bet is over 6,000 miles from the source. The best-preserved specimen of this flightless bird, once native to the island of Mauritius, is found in the United Kingdom, at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History. But new research from the University of Warwick tells a troubling story about the bird’s demise, revealing a “violent death,” likely caused by gunshots to the head and neck.

The bird was believed to have arrived in London sometime in the mid-17th century, when it was trotted out for curiosity shows of rare and unusual creatures. Eventually, the story goes, it died of natural causes, and found its way into the personal collection of John Tradescant the Elder. The bird’s remains eventually wound up in Oxford.

But analysis of the head and neck by scientists showed mysterious flecks of what eventually turned out to be lead shot pellets, used in fowl hunting at that time. “When we were first asked to scan the [Oxford] Dodo, we were hoping to study its anatomy and shed some new light on how it existed,” researcher Mark Williams said in a release. “In our wildest dreams, we never expected to find what we did.”

The discovery calls into question the entire history of the animal and how it made it to the museum. Either the great performing dodo of yore was shot, and the story covered up, or the bird on display, which inspired Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland character, is another creature altogether. “There is now a mystery regarding how the specimen came to be in Tradescant’s collection,” Paul Smith, the director of the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, told LiveScience. “The even greater mystery is, ‘Who killed the dodo?’”

As the only known specimen with soft tissue from which DNA can be extracted, this bird has proven a crucial object for study—to find it out how it lived, what it ate, who its closest living relatives are. This was what Williams and his team were hoping to investigate, when they micro-CT scanned the bird in Warwick, north of Oxford. But their scan told them more about its death than its life, Williams said. “This is a flightless bird, so obviously, somebody snuck up behind the poor thing and just shot it in the head,” he told LiveScience. It’s hoped that further analysis of the lead pellet may reveal whether it died in Mauritius, on the journey, or in the United Kingdom—a sad end for one of the last of its kind.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook