Star Forts Are Military History, and the Base of Some Strange Conspiracy Theories

Examining why these ubiquitous, obsolete fortifications carry an air of mystery.

On an unseasonably cold day in late March, I took a nearly empty ferry to Governor’s Island in New York Harbor. The sun was shining, but a brutal, frigid wind meant it was hardly a day for a picnic, a popular reason to visit the island in the summer. I disembarked onto a nearly deserted island, one that would have been utterly quiet if not for the near-constant sound of private helicopters taking off from and landing on the lower tip of Manhattan. I was there to see the star-shaped Fort Jay, a coastal defense built between 1794 and 1806, one of a series of fortifications that once protected the city and its harbor, and recently recast as a historic monument and spot for summer recreation. It’s notable for its striking structure—a kind of five-pointed star, a shape that has led to its inclusion in a strange conspiracy theory about the nature of the past and humanity itself.

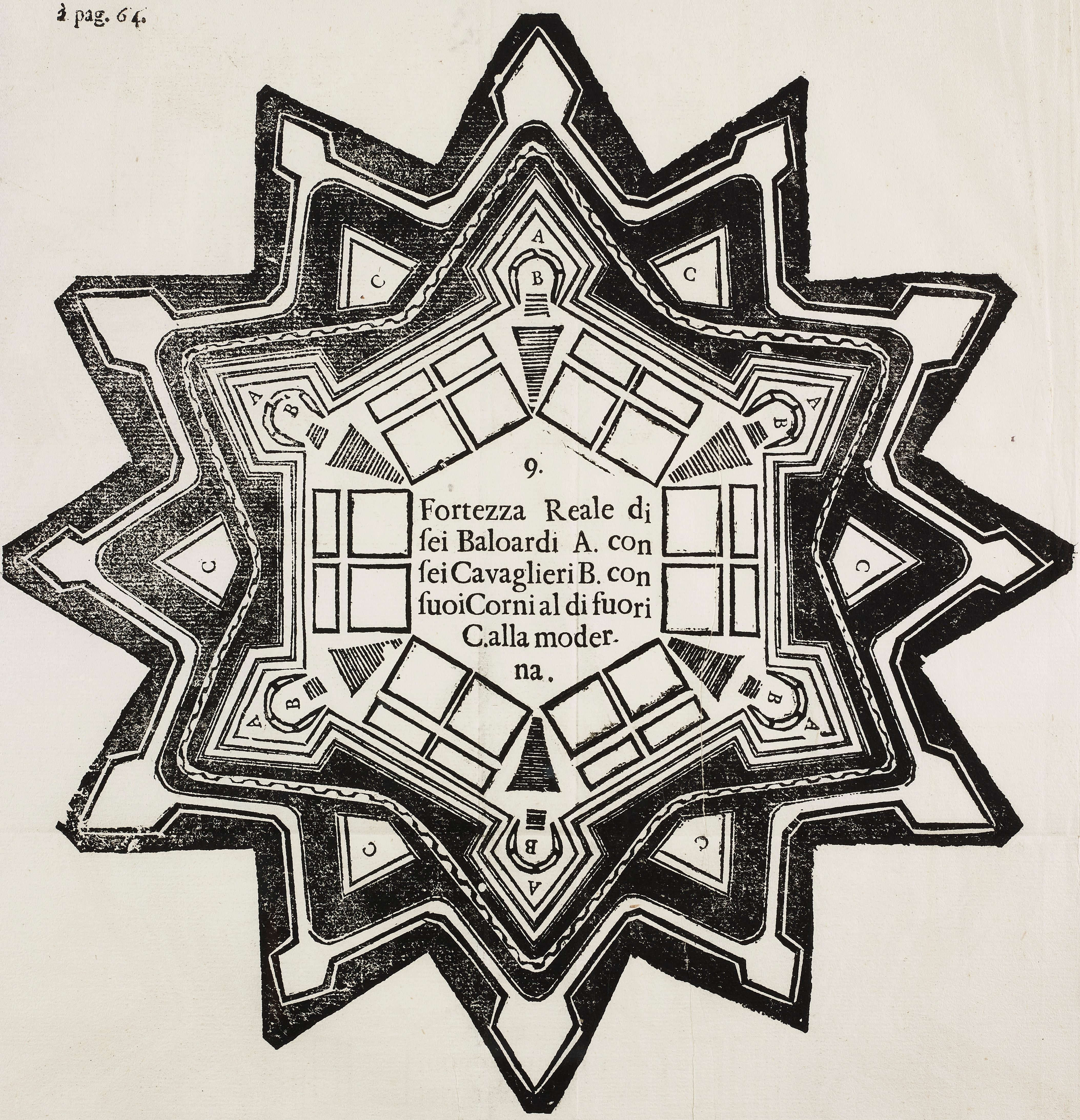

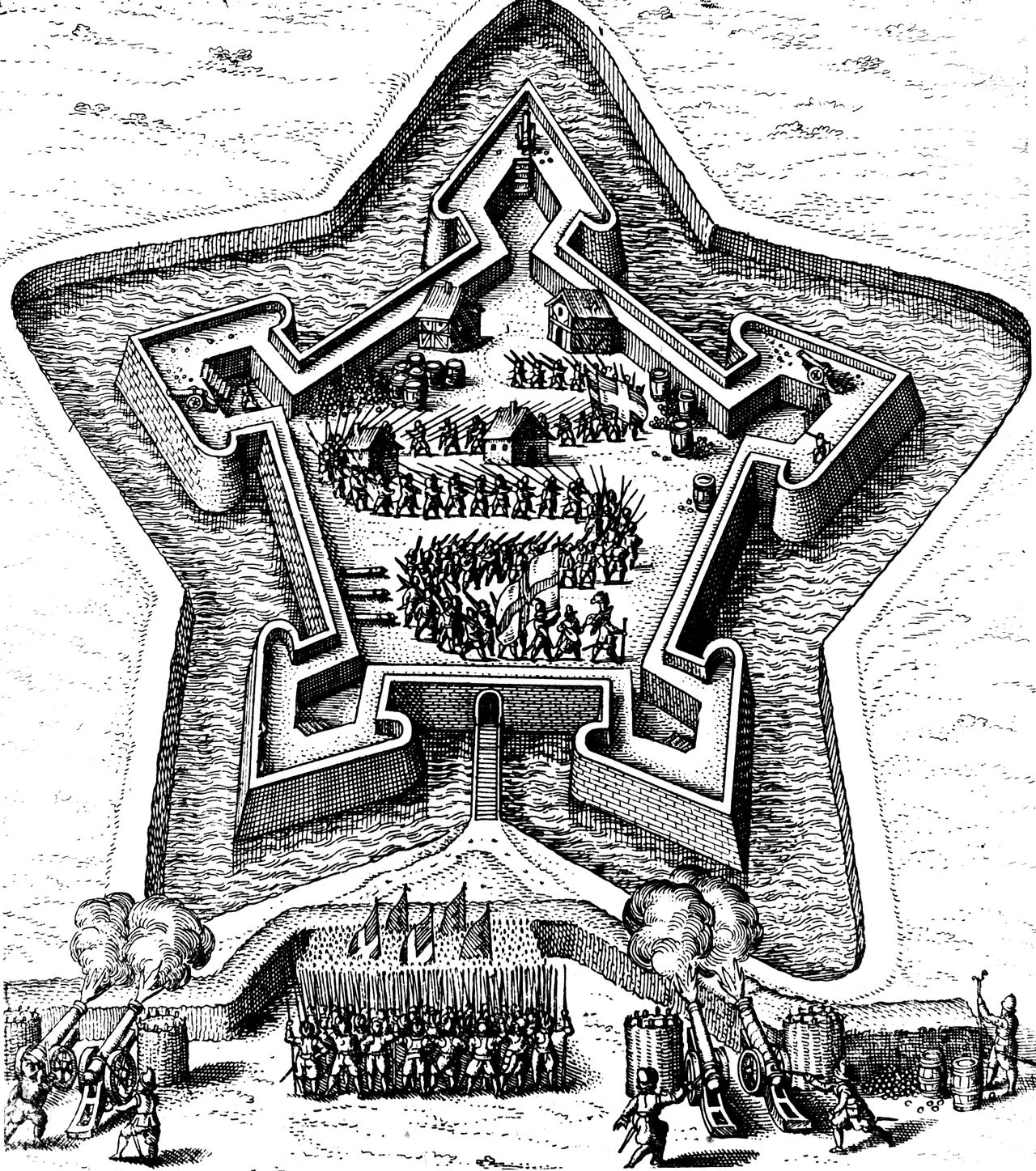

The evolution of European-style fortresses from square with rounded turrets at the corners to pointed bastions like the ones on Fort Jay was a result of simple geometry and technological progress. While the traditional structures could easily be defended by archers, those same turrets created blind spots for cannons, which could not be maneuvered as easily or fired directly downward from the top of a battlement. The pointed bastions solved this problem by eliminating blind spots: Cannons could be placed at the wide end of a bastion, and pointed down along the long line of the adjacent walls to defend against armies attacking from any direction.

I first began thinking seriously about bastion forts after reading W.G. Sebald’s final novel, Austerlitz. The book centers around the eponymous architecture critic, Jacques Austerlitz, who explains to the protagonist early on that “it is often our mightiest projects that most obviously betray the degree of our insecurity.” Describing the evolution of bastion forts throughout Europe, Austerlitz describes how they betray a “fundamentally wrong-headed idea: the notion that by designing an ideal trace with blunt bastions and ravelins projecting well beyond it, allowing the cannon of the fortress to cover the entire operational area outside the walls, you could make a city as secure as anything in the world can ever be.”

“No one today,” he continues, “has the faintest idea of the boundless amount of theoretical writings on the building of fortifications, of the fantastical nature of the geometric, trigonometric, and logistical calculations they record, of the inflated excesses of the professional vocabulary of fortification and siegecraft, no one now understands its simplest terms, escarpe and courtine, faussebraie, réduit, and glacis, yet even from our present standpoint we can see that towards the end of the seventeenth century the star-shaped dodecagon behind trenches had finally crystallized, out of the various available systems, as the preferred ground plan.” Fort Jay has only five points—a much-simplified version of the plan Austerlitz describes—but Fort Wood, just across the harbor on what was then called Beldoe’s Island, has a full 11 points. It was completed around the same time as Fort Jay, but it has since been converted into the base of the Statue of Liberty.

There are hundreds of these structures still standing today; they can be found everywhere from Antigua to Taiwan and from Ireland to Venezuela, though the vast majority of them are in Europe (there are dozens still standing in France alone, and nearly as many in Italy) and in former European colonies (the East Coast of the United States has dozens from Maine to Florida, and five dot the coast of Ghana, remnants of the Dutch and Portuguese occupations). They were first developed after the fall of Constantinople in 1453, and became widespread throughout the 16th century, until their gradual obsolescence became apparent in the 1800s.

As massive structures meant to withstand direct hits from cannon fire, they’re formidable and not easily removed, and they’ve lingered in the landscape long after they ceased to have any use. What lies behind these structures, then, is a fully accessible but bizarrely complex archive of architecture and military history, but one that has lost all utility or interest, even as the structures themselves persist. We are doomed, it would seem, to be surrounded not just by structures that not only outlast us, but whose very nature eludes and confounds us.

I returned to Sebald’s novel again as I learned that there is an entire conspiracy theory built around these fortifications. According to the stranger corners of the Internet, these forts are not elaborate remnants of long-obsolete defense strategies, but rather structures built by some lost, hyper-advanced civilization. “Let’s be clear from the outset,” the website starforts.org states, “the starforts that remain today, either intact or in ruins, were part of a far larger network of a lost civilisation [sic] that spanned pretty much—as far as we can tell—the entire Earth. This is a bold claim, but there is a growing body of evidence to support such a claim. Research is ongoing.” The various fortifications of various countries engaged in various hostilities have been linked together, their lingering presence taken as evidence of some vanished empire.

Littered all through Youtube, TikTok, and Reddit are videos and threads with names like “Star Forts: Tesla Technology, Vibration Healing, Ancient Electricity, Sound Frequency Technology,” in which bastion forts are recast as key players in the New Age gobbledygook that makes up so much of social media these days. (Among the regular posters in the starforts.org thread is a man named John A. Warner IV, the son of former U.S. Senator and U.S. Secretary of the Navy John Warner III, who’s self-published a novel that involves star forts, among its many other plots, and argued, for example, that they were not built but rather “grown” through some combination of frequency resonance and “water cymatics,” whatever that is.) What unites these various strands of conspiracy is that the star forts are somehow capable of harnessing electromagnetic energy through their structure, and that they thus act, in some sense, as free energy generators. The star pattern, these conspiracists allege, mimics certain frequency waves as they appear on oscilloscopes, suggesting that these structures’ design reflects not military technology but an organic shape that somehow harmonizes with the natural world.

If this makes little sense to you, don’t worry; even the most cogent and direct articulation of the theory is bizarre, contradictory, and relies on question-begging and obfuscation. As with many conspiracy theories, the Star Forts hypothesis depends on a willful, obtuse misreading of evidence. “Star Forts are all over the world but nobody can really explain them,” reads one post on X; another conspiracist explains in a video, “I’ve looked at star forts, folks, and they just don’t cut the mustard with regards to ‘this a defensive building,’ they’re just not defensible. I mean yeah you can defend them, and you could fortify them, but they couldn’t have been built for that purpose, when you look at them, it just doesn’t make sense.” In another, Fort Prince of Wales, a remote bastion fort in northern Manitoba, is singled out for, at some point in its history, having been repointed (“the only reasoning one can deduce is that the mortar is nothing more than cosmetic”), one of a series of very obvious elements of the building’s past that are held up as inscrutable mysteries, before the vlogger concludes: “This building was found, rather than built.”

Why this strange obsession with proving that these defunct structures hold a deeper meaning? As secret power generators, so the story goes, they once held the key to free energy; if we could awaken them, we could not only be free of fossil fuels, but we could end war and poverty. That is why, according to these conspiracists, their true nature has been hidden from us. The star forts mythos is a further elaboration on the various conspiracy theories involving nuclear fusion, the water-fueled carburetor, Nikola Tesla’s perpetual motion machines. It alleges that a secret global cabal is responsible for the strife, suffering, and deprivation of the modern world—and that the answer to all our problems is hiding in plain sight.

None of this is, in itself, particularly new. At least since Erich von Däniken’s Chariots of the Gods? was published in 1968 (the question mark was later dropped from the title), revisionist history has long postulated that great and unusual structures are the work of aliens. The star forts theory comes from the same playbook, just with a focus on well-documented, modern fortifications rather than, say, the Pyramids. Beliefs about pre-European civilizations being the work of extraterrestrials is a long-standing trope that reeks of Western chauvinism and racism—a way to discount the art and architecture of the Egyptians or the Maya, or the math and perspective that the ancient Nazca culture of Peru used to lay out the massive figures of the Nazca Lines.

What’s stranger about the star fort conspiracy theory, then, is that it estranges Westerners from their own culture—these are not buildings constructed thousands of years ago and left in ruins, but were made by the conspiracists’ own ancestors, and explained in great detail in writing that is easily accessible to readers of English, French, and German. Any sense of mystery here is entirely, willfully manufactured.

Perhaps this is why I felt compelled to go back to Fort Jay, the nearest extant bastion fort to where I live in Brooklyn. It lies just off the ferry terminal, down a road that ascends to the mound that the fort was dug into. Because it’s largely sunken into the ground, it’s far from imposing and barely rises above the landscape. You have to crest the hill to get a sense of it, though even then you’re not nearly high enough to see the whole plan at once. Instead you have to walk its perimeter.

The deep moat separating the fort from the surrounding hill remains, and though the grass is tended, it still evokes a sense of distant ruins, with earth and grass everywhere coming up to—and in some cases covering—the stone battlements now 200 years old. As a National Park site, there are small placards at key places explaining its history, but they give little detail. Of the building’s shape, they state only that it “was commonly used in fortifications because it gave defenders effective angles of fire.”

One of the features of a fortification like this is that it’s impossible to take it all in at once. Rather than an imposing façade like a cathedral or a castle, Fort Jay presents as a series of long, squat brick and stone walls, in multiple directions, with acute zigzags in trajectory. At no point does it suggest its star shape; it doesn’t suggest any kind of shape at all. It feels haphazard, if implacable. Only when you look at a ground plan do you see the overall shape.

In my periphery, across the harbor, was the rebuilt World Trade Center, a vague reminder of the precarity of the country’s security. It was strange to see a fortification like this in 21st-century America, which hasn’t been formally invaded in centuries. In Sebald’s Austerlitz, such buildings are less evidence of powerful defense than of a specific form of madness. For, as Austerlitz points out, there is an obvious flaw in these designs: “a tendency towards paranoid elaboration,” he explains, ends up drawing “attention to your weakest point, practically inviting your enemy to attack it, not to mention the fact that as architectural plans for fortifications became increasingly complex, the time it took to build them increased as well, and with it the probability that as soon as they were finished, if not before, they would have been overtaken by further developments, both in artillery and in strategic planning, which took account of the growing realization that everything was decided in movement, not in a state of rest.”

The ruins that surround us, he suggests, are not always the result of clever planning, thoughtful foresight, or a measured desire for peace or even legacy—but rather they are themselves manifestations of the workings of paranoid minds. The same way a thought or sentence or conversation might spin out of control, so too can a wall of brick and mortar. So it might seem we remain surrounded by legacies of paranoia, onto which we project our own paranoias. “At the most,” Austerlitz explains elsewhere, we gaze at such structures “in wonder, a kind of wonder which in itself is a form of dawning horror, for somehow we know by instinct that outsize buildings cast the shadow of their own destruction before them, and are designed from the first with an eye to their later existence as ruins.”

But paranoia, mediated by architecture, does not always beget paranoia—at least not entirely. For me, the main affective emotion generated by the star forts conspiracies is a kind of melancholy. There seems to be, hidden among all the strange explanations and justifications, a bizarrely utopian aspect to this particular conspiracy theory. As one person wrote in the starforts.org forums, “The starciv phenomenon gives me hope. It shows that a worldwide society has existed that could work together to make the world a beautiful place, working with nature—and guaranteeing the best future possible for everyone. It is possible, because it has already existed. The world hasn’t always been at war—the starciv is the proof of that.” By (falsely) recasting these fortresses as ancient power generators, they wipe away the long history of war and strife they actually represent.

Such thoughts, however hopeful, require the active destruction of historical memory, and sustaining such a wide-ranging theory requires so much of it. Everything needs to be reduced to the level of Egyptian hieroglyphics—a distant, purportedly unreadable text (of course, we can read hieroglyphics) that can be re-interpreted by amateurs at will.

Perhaps Sebald was right in supposing that such massive projects betray a deep insecurity, and that despite their thorough construction of brick and stone, they already prefigure and imagine their own destruction. But that destruction, it seems, comes not from artillery or the wrecking ball, but from the obliteration of the past that could give such places context and meaning.

I see human history as one involving—yes—pain, strife, catastrophe, and folly, but also the potential for strange grandeur, unexpected beauty, and the perseverance of justice even in times of great darkness. I see a past that is complicated but wondrous, filled with disorder and chaos but never without moments of redemption. Conspiracists, on the other hand, want to reimagine the future by destroying any sense we have of the past.

I once stood at the foot of such battlements and experienced a kind of sublime awe, a sense of the weight of history, compacted. Now I’m more often likely to feel a kind of anxiety. Whereas the conspiracists are estranged from the past and the architectural world around them, I feel estranged from them and my fellow human community. We stare at the same building and see two entirely different things.

Colin Dickey is the author of five books of nonfiction, including Ghostland: An American History in Haunted Places, and, most recently, Under the Eye of Power: How Fear of Secret Societies Shapes American Democracy. He also hosts Atlas Obscura’s Monster of the Month.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook