Everything You Know About Mole Sauce Is A Lie

If what you know is that mole’s most important ingredient is chocolate.

Different mole sauces on display in Oaxaca. (Photo: David Boté Estrada/CC BY-SA 2.0)

If you were to set up a word association game in which you tell Americans the word mole, the Mexican sauce, it’s pretty likely that the response will be “chocolate”.

When an archaeology team discovered traces of chocolate on a 2,500-year-old plate in the Yucatan in 2012, they described the possibilities this way: “It would also suggest that there may be ancient roots for traditional dishes eaten in today’s Mexico, such as mole, the chocolate-based sauce often served with meats.” Recipes for mole, even from noted chefs, very often present a chocolate-containing sauce as simply “mole,” as though a mole must gain its specialness and power from chocolate. Possibly this is because chocolate, until recently, was not often used in savory dishes in the U.S.; our understanding of chocolate is almost universally sweetened and made mild with dairy.

Ingredients for a mole negro. (Photo: Matt Murphy/CC BY 2.0)

“People think that mole is a sauce made from chocolate,” says Pilar Cabrera, the chef of Oaxaca’s La Olla who also runs a cooking school in the city. But nope: “Chocolate is not the main ingredient and is only added to the more complex moles.”

In fact most moles do not contain chocolate, and either way, chocolate is certainly not an element that makes a mole a mole. Looking more deeply into this sauce reveals that its history and impact are as complicated as a 35-ingredient mole poblano. This most traditional of Mexican foods is one of the most fluid, ever-changing items in the country’s culinary history—and all this coming from what might well be the first well-known dish to combine ingredients from the New World with those from Europe, Africa, and Asia.

Most moles do not, in fact, contain chocolate. (Photo: Edsel Little/CC BY-SA 2.0)

Different food traditions approach sauces differently. The French, for instance, use a few different basic sauces, known as “mother sauces,” which can be either served as-is or modified by adding various flavors to create new variations. Mother sauces, which include well-known options like hollandaise and bechamel, have one thing in common, as Lucky Peach spells out in a nice post: they are composed of a stock combined with a roux. The stock can change—chicken, beef, vegetable, rabbit—but roux is, at its core, a simple combination of butter and flour. The roux ingredients are mixed and cooked to the desired color, and serve as a thickener, creating a glossy, fatty, luxurious texture.

Mole can be seen as the Mexican version of the mother sauce, albeit with some revealing alterations—and with the noted exception that mole is just one “mother” of many (cold sauces, or salsas, come from an entirely different family tree). “What all moles have in common are the following,” says Zarela Martinez, the Sonoran-born ambassador of Mexican cuisine to the U.S. who has, as she says, done just about everything, from restaurants in New York to cookbooks to PBS shows. “They’re all pureed, they all contain chiles, either fresh or dried, and they all have aromatics, like onions, roasted garlic, tomatoes or tomatillos. The other thing that they all share is that they have some kind of thickener, which can be nuts, seeds, bread, or tortillas, or some of all of the above.”

If this sounds complicated, well, yes, it is complicated. Mole is not a specific dish, or even an array of dishes, with traditional lists of ingredients that should not be modified. Mexican cuisine is so hyper-local, so varied based on not just region but individual town, that the very few items that are truly eaten nationwide are required to be extremely versatile. Mole is really more a concept than a dish.

Chiles, an essential part of mole, on sale in a market in Oaxaca. (Photo: Jesús Dehesa/CC BY-ND 2.0)

The word mole comes from the Nahuatl word mōlli, which Martinez says means “to grind,” or “ground.” Other sources, like Cabrera, say it means “sauce.” Its origins are mostly unknown; there are several stories about its creation, usually involving a visiting religious leader and a cook with small amounts of many ingredients but not much of any, forced to combine them all.

The basic procedure for making a mole, with some exceptions, involves preparing many, sometimes dozens, of ingredients separately and then combining them into a powder or paste before mixing with stock. Chiles are essential, but Mexico has literally hundreds of varieties of chile, and individual moles will use varying combinations to achieve a certain balance of flavors: some chiles are used for sweetness, others for spice, for smokiness, for umami, for crisp freshness, all kinds of things. Seeds, like pumpkin and sesame seeds, are common. Tomatoes and tomatillos are common, as are garlic and some variety of onion. Herbs, either dried or fresh, may include epazote, hoja santa, or more familiar herbs like oregano and thyme. Dried fruits like raisins and figs, and fresh fruits ranging from pineapple to apple, are used, sometimes. Nuts are common, especially almonds, peanuts, pecans, and pine nuts. Spices may also be used: allspice, cumin, clove, cinnamon (technically the bark of Canella, which tastes similar to the true cinnamon found in Asia), coriander. The thickness of the mole can vary as well; some are very thick and used as fillings, others can be thinned to nearly the consistency of a hearty soup’s broth.

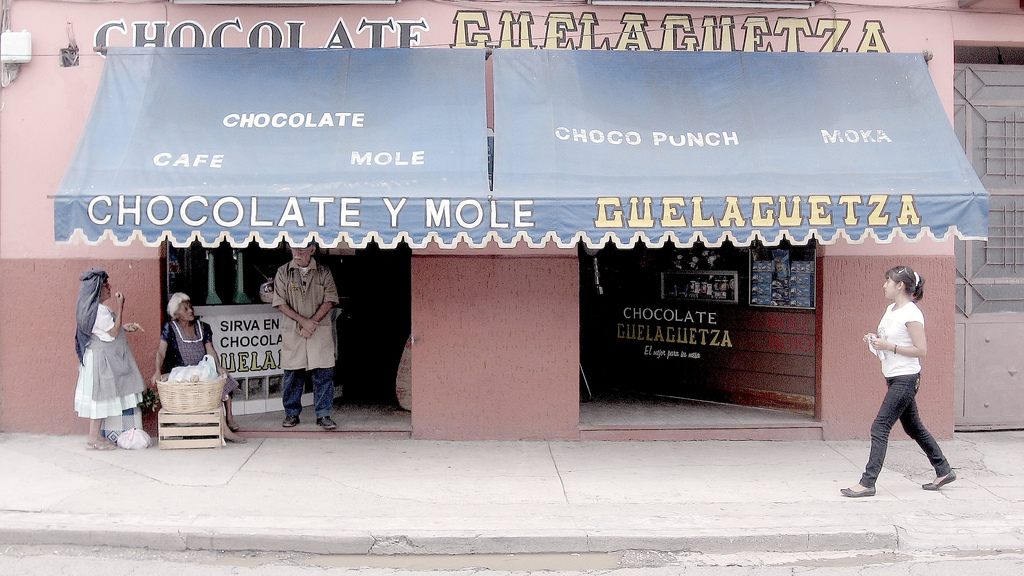

A storefront in Oaxaca. (Photo: 16:9clue/CC BY 2.0)

The global influence on the mole comes largely in the spices; at the time the Spanish conquered Mexico, there was a heavy Moorish and Arab influence in Spain, and those spices arrived with the conquistadores. In certain states, especially Veracruz, the Arabic influence really took hold, bringing treasured food items like al pastor (the carved meat-on-a-stick dish with obvious roots in shawarma) as well as spices like anise, clove, and black peppercorn.

As to chocolate, only a few of the ultra-complex, dark, celebratory moles use it. “And usually the one that’s used is bitter, even though everybody uses that Abuelita,” says Martinez, referring to a popular brand of chocolate made by Nestle. Martinez doesn’t much like it; she finds it too sweet, and prefers to use a very bitter variety from Oaxaca. Chocolate may be a more recent addition. Though written history is limited from pre-Hispanic Mexico, chocolate seems to have mostly been used as a beverage rather than a flavoring agent in food.

The preparation is laborious and complex for most moles; each individual item must be cooked to perfection, then removed, then ground, then combined over heat while constantly stirring to avoid burning. Some items must be added at certain times in the process; some items must be cooked using different equipment. The combination of so many strong flavors into one harmonious, single-consistency sauce is a ridiculously difficult task, one that makes emulsifying a perfect hollandaise seem as simple as stirring Kraft cheese powder into milk.

Mole verde. (Photo: JuanSalvador/shutterstock.com)

Rarely, mole can be simple; mole verde uses almost exclusively fresh ingredients, most often tomatillos, pumpkin seeds, and fresh cilantro. It can be constructed in less than half an hour, and its bright, light flavor pairs well with delicate items like vegetables and chicken. Other, darker, more sinister moles are served with other proteins, but perhaps the most important, clarifying element is that the mole is not a sauce to enhance a protein, as it is with the French mother sauces; instead, the proteins are used to accent the mole. The sauce, unlike most sauces, is the star.

Mole verde is one of the famed seven moles of the state of Oaxaca, though of course there are many many more than those seven to be found there. “In reality there are a lot more moles, because in every region they are used to a different mix of ingredients, and in Oaxaca we have 8 regions and more than 570 municipalities,” says Cabrera. Oaxaca, with nearly half its population identifying as indigenous, is a powerhouse of the pre-Hispanic mole. Probably the state’s best-known version is mole negro, a murderously difficult mole involving dozens of ingredients including avocado leaves, at least five kinds of chiles, and, yes, chocolate.

A typical celebratory small-town meal, Martinez said, might well include barbacoa, from which the word “barbecue” comes, along with rice, beans, and a mole. But mole, as a flexible concept, has come to be embraced by chefs eager to push it to new places. It is often served over enchiladas, with eggs, or in all kinds of other applications. Martinez makes it with fideos, broken pasta, in a casserole, and in a sort of lasagna with mashed plantains taking the place of pasta. These newer takes on mole provide some interesting clues as to where the dish’s evolution is going; it has always been a dish arising from the confluence of foreign influences, and that pattern is, if anything, only speeding up. Mole isn’t less traditional or authentic if it comes in the form of a lasagna. This is the way it’s always been.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook