What I Learned About a Pioneering Black Cookbook Author by Cooking Her Recipes

Little is known about the first African-American woman to publish a cookbook.

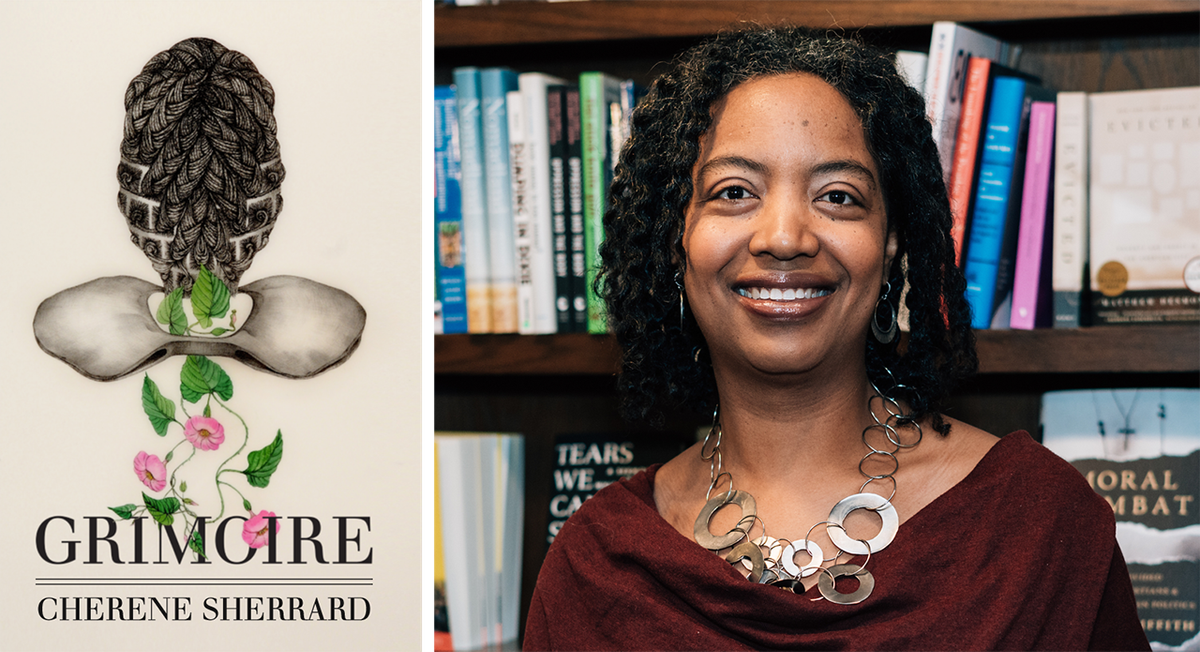

The author’s book of poetry about Malinda Russell, Grimoire, was published in September 2020.

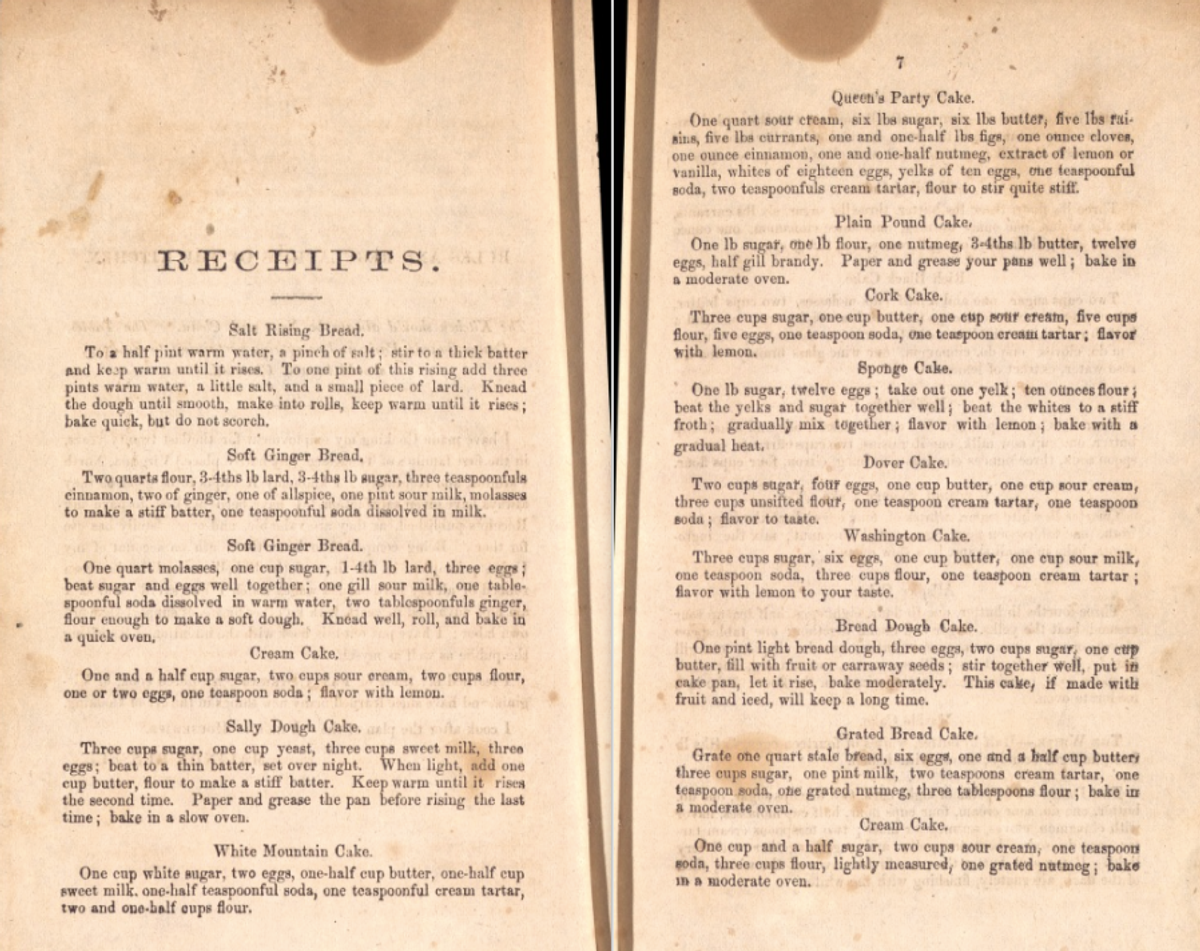

From the moment I held the reprint of Mrs. Malinda Russell’s A Domestic Cookbook: Containing A Careful Selection of Useful Receipts for the Kitchen, I was smitten. The 39-page volume is the first known cookbook written by a Black woman: Russell was born in eastern Tennessee to a mother whose family had been freed in Virginia, and, during the Civil War, left behind her pastry shop as she fled to Michigan, where she wrote A Domestic Cookbook. An original copy, which was rediscovered by culinary curator Janice Bluestein Longone, resides in the University of Michigan’s Clements Library.

Beyond a scant autobiographical prelude, though, we know few details about Russell’s life, which is sadly common. Faced with incomplete archives, many scholars, writers, and artists have invented creative means to envision the world of underrepresented, “minor” subjects. Saidiya Hartman’s Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls Troublesome Women, and Queer Radicals blends factual analysis and narrative nonfiction to paint a textured portrait of the unsung and overlooked. Captivated by Russell’s unique story, I scoured her recipes for clues and prepared them in the same way blogger-turned-bestselling-author Julie Powell cooked through Julia Child’s Mastering the Art of French Cooking. My desire to recover her distinctive voice and fill in archival gaps inspired Grimoire, my poetry collection that is also a conversation between Russell and a 21st-century mother and cook.

African-American cookbooks are a tremendous resource for communicating the experiences of everyday Black life across time. Writers such as Russell and Abby Fisher, the author of What Mrs. Fisher Knows about Old Southern Cooking, Soups, Pickles, Preserves, etc (1881), confirm that Black cooks were far more than support staff for their white employers, many of whom wrote cookbooks claiming or misrepresenting their recipes. When I first encountered sepia images of Russell’s pages in Toni Tipton Martin’s The Jemima Code: Two Centuries of African American Cookbooks, I wondered: Who was her audience? Are the “ladies” she refers to her white clients, or other free women of color? And who was Fannie Steward, the Black cook who trained her?

We may never fully know the answers to these questions, but the recipes in A Domestic Cookbook offer a rare and tasty glimpse into the life of a free Black woman entrepreneur before and after the Civil War. Russell’s oeuvre is surprisingly continental. Few of her dishes resemble Southern cuisine or recipes typically credited with African or African American influences, such as peach cobbler or sweet potato pie. Russell likely catered to the taste of white families with disposable income and aspirational taste. Although she modeled her style after Mary Randolph’s The Virginia Housewife (1824), a popular cookbook that emphasized household organization, she added her own flair. Perhaps she took private delight in including recipes for blanc mange, a custard similar to a panna cotta, and a Charlotte Russe cake, a complex French confection created in the 1820s. Contemporary cooks recommend assembling this no-bake cake from prefab ladyfingers, but Russell’s recipe, one of the longest in her book, requires chilling the Bavarian cream in the snow.

Russell takes for granted a moderate level of expertise. Some recipes are simply a list of ingredients reading like a technical challenge from The Great British Bake Off. A novice wouldn’t know where to begin when faced with a one-sentence recipe for “Bride’s Cake” that calls for 24 eggs beaten to a stiff froth and baked with “gradual heat.” The “receipts,” as she calls them (using an archaic word for recipes), include an extensive assortment of cakes, puddings, sweet breads, and cordials; a few extravagant main dishes such as “Potted Beef” or “Calf’s Head Soup”; and preserved fruits, pickled veggies, and medicinal elixirs to soothe common ailments. (Early cookbooks often contained home remedies for rheumatism, toothaches, or hair-coloring.)

In my attempts to revive her creations, I stuck to the sweets. I see myself as more of a baker than a cook: an inheritance from my maternal grandmother, Hattie Cochran, who taught her two daughters some, but not all, of her secrets. My mother can replicate her seafood gumbo from a three-page, hand-written recipe. But the scrumptious, savory dumplings in her chicken stew? Impossible. Monkey bread baked in a Bundt pan? No dice. Like the scattered family histories of many of slavery’s descendants, these are lost recipes.

Recipes, like certain poems, are often comprised by imperatives: take this, whisk that, or add a generous pinch. Underlying the instructions is a veiled threat: If you deviate, you may not get what you want. Russell raises more questions than she answers. Tucked in between directions for “Graham Cakes” and “Mrs. Roe’s Cream Pie,” she advises: “first heat the oven hot enough for cooking, set in my cake, and open the door; and for a common sized cake leave the door open for about fifteen minutes, and for a large one about twenty minutes. When the cake begins to raise, close the door.” My gas oven’s temperature fluctuates wildly. If I followed Russell’s lead, the results could be disastrous. Still, her sparse invectives leave room for improvisation. Her invitation to open the oven was a dare I couldn’t resist.

Ultimately, my recipe re-ups had uneven results—my cake had the density of sweet bread—but I painted a fuller, permanent portrait of her life through poetry. In a poem about how dessert can be a salve for separated lovers, titled “Things to do with Ginger,” I remixed “Soft Ginger Cake” as “Sponge Cake soaked in coconut rum spangled with shards of crystallized ginger.” Another poem, “Liberian Ballad,” recreates her courtship with Anderson Vaughan, her husband of four years, against a backdrop of African repatriation. At 19, she planned to emigrate to Liberia, where she hoped to become a “valuable citizen.” During the Civil War and Reconstruction, thanks to the efforts of the African Colonization Society, a subset of African Americans returned to the African continent. Russell was brave enough to attempt an Atlantic crossing, but abandoned her travel plans following a robbery. I imaginatively transport Russell and her new husband into the pastoral vista of the promised land portrayed in Augustus Washington’s landscape View of Monrovia from the Anchorage (1856). The ballad is the perfect form for their abridged romance. Instead of beginning a new life in Liberia, Russell ended up in Michigan as a widow with a young son to support.

We have no idea how her husband died, but we can grasp her desperation. Making her way across Union lines in the midst of the Civil War was incredibly dangerous. On her journey, Russell recounts being “attacked several times.” In my poem “The Robbery,” I highlight her tenacity as she outwits a “guerrilla party” by hiding her “hard-earned wages” in her petticoats. Despite her free status, as woman of African descent, Russell’s civil rights were not recognized by U.S. courts. The 1857 Dred Scott decision confirmed that the protections and privileges of U.S. citizenship did not apply to Black Americans. The 1850 Fugitive Slave Act encouraged entrapment of freedmen and women without regard for their papers, like Solomon Northup in 12 Years A Slave.

Once she arrived in Paw Paw, Michigan, with her disabled son, it took gumption to decide to publish a cookbook. Each page of A Domestic Cookbook reflects her resourcefulness and conviction. We can’t trace how many copies she sold, but we believe her when she tells us that “a great many ladies have wished to know how I have such good success making my cakes so light.” Writing Grimoire was also an act of faith. Would these poems, spun from autobiographical slivers, express emotional, if not factual, truths? By recording and publishing her recipes, Russell had the audacity to envision a future in which Black women would create and improvise with confidence. I sought to capture her adventurous spirit, the urgency of balancing her own desires with the needs of her son, and the breadth of the cosmopolitan palate displayed in A Domestic Cookbook.

Tracing Russell’s journey complicates easy assumptions about the lives of early African Americans. Race and gender rendered her a non-person in the 19th century, and yet she managed to communicate with authority. Koritha Mitchell writes about how Black women have had to rely on “homemade citizenship” in the face of what she calls “know your place aggression.” Russell applied the same aptitude used to perfect her culinary skills to negotiate a place for herself in an inhospitable nation. Despite the loss of a thriving business, she reinvented herself as an author. In sharing her knowledge, she shrewdly hoped to sustain a life for herself and her son.

Following Russell’s instructions more than 150 years after she published A Domestic Cookbook, I honor her labor and realize the courage it took to claim a place for herself as a professional. Adapting and sharing her “receipts” was a generative process that expanded my creative and culinary repertoire. Resurrecting Russell’s dishes through poetry allows me to sample an edible past and recover a culinary legacy that extends beyond the kitchen.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook