For Sale: The First Printing of ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’

A celebration of freedom, published next to advertisements for the slave trade.

On September 10, 1814, so its staff could help defend against the British Army, the Baltimore Patriot and Evening Advertiser temporarily ceased publication. Ten days later the newspaper returned with a blockbuster column on its second page. Its text would go on to become iconic—anthemic, even.

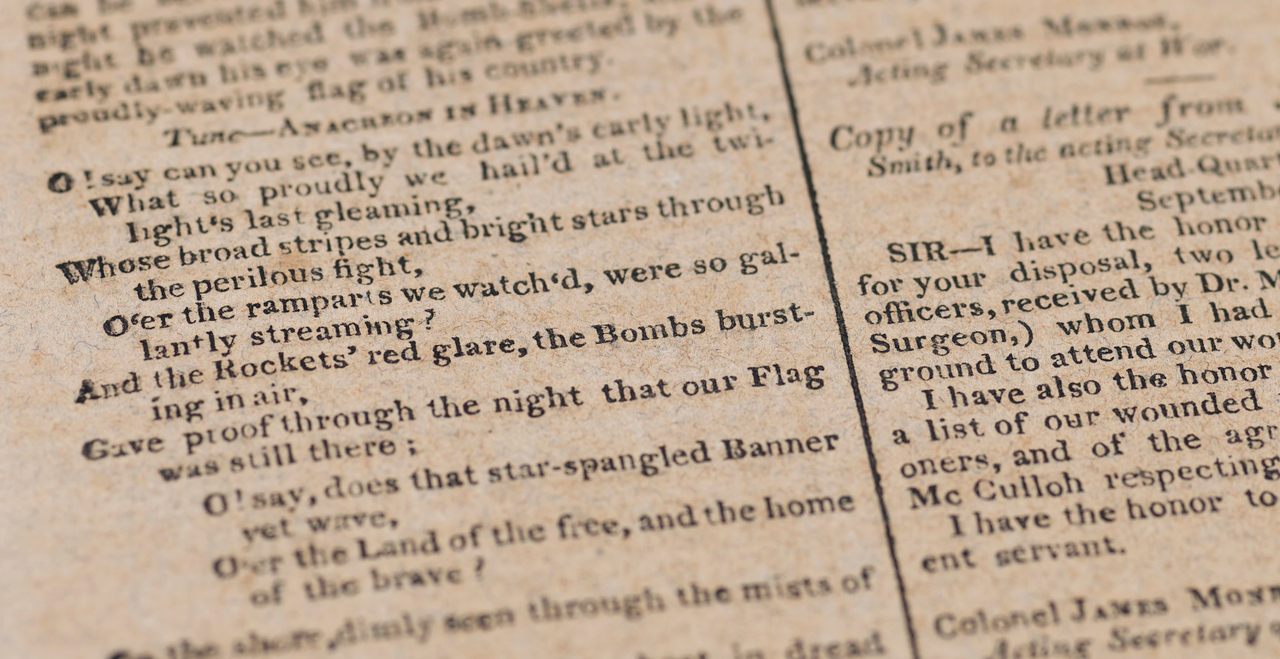

Printed under their original title, “The Defence of Fort M’Henry,” the four verses allowed the newspaper to report on the events of the titular battle with some literary flourish. “In our first renewal of publication,” the editors wrote, “we rejoice in an opportunity to enliven the sketch of an exploit so illustrious, with strains … which so fully celebrate it.” The paper also predicted that the words were “destined long to outlast the occasion,” but it’s doubtful the editors understood just how long. In June 2020, more than 200 years later, this first newspaper printing of what became “The Star-Spangled Banner” will be auctioned by Christie’s, for an expected minimum of $300,000.

Accompanying the lyrics is a reported account of the song’s conception. The writer, Francis Scott Key, had been captured by the British when they arrived in Baltimore Harbor on September 7, 1814, after taking Washington, D.C. (Quick chronology check: This was the War of 1812, which lasted until 1815.) From that captive position, Key watched the bombardment of the fort “with an anxiety that can be better felt than described,” the newspaper put it. The British had momentum, and their “Admiral had boasted that he would carry [Fort McHenry] in a few hours, and that [Baltimore] must fall.”

To Key’s shock, however, “his eye was again greeted by the proudly-waving flag of his country” after the long night of fighting between September 13 and 14. He returned to Baltimore with the American victors, and wrote the song on September 16 from his room in an inn. Just as he did in 1798, when he wrote “The Warrior Returns” (which first used the term “star-spangled”), Key set the new verses to the tune of the English drinking song, “To Anacreon in Heaven.”

It’s hard to know exactly why. Ellen Dunlap and Lauren Hewes, of the American Antiquarian Society (the lot’s consigner), say it may be because the song was well-known, so large gatherings would’ve been able to sing along with the new words. But as Peter Klarnet, a senior specialist at Christie’s, points out, it’s “not an easy song to sing,” with “octaves all over the place.” In that regard, it’s somewhat surprising that it eventually became the national anthem, though its association with the flag and invocation during flag rituals ultimately helped its case. Of course, the title was also changed to refer to the flag: Klarnet says “The Star-Spangled Banner” first appeared as its title in printings at a Baltimore music store in November 1814.

The song wouldn’t officially become America’s national anthem until 1931, and it’s typically only the first verse that ever gets sung. Though that first verse has itself become a site of protest over the decades, it’s the overlooked third verse—even if you interpret it generously—that most complicates the national mythology the anthem conjures. “No refuge could save the hireling and slave,” wrote Key, “From the terror of flight or the gloom of the grave … ”

It’s possible that this line refers to enslaved African-Americans who joined the British forces in hopes of securing their freedom; more than 4,000 are believed to have done so. In this reading, Key is mocking those who escaped and joined forces with the losing side, and sort of celebrating their demise. Though some contend that the line does not intentionally reference those escaped slaves, it’s a reminder of the contemporary reality, one also documented in the issue of the Baltimore Patriot.

The paper’s front page, preceding the song, is populated by advertisements—at least five of which are notices regarding slavery: rewards for escaped slaves, sale advertisements, and announcements of the apprehension of escaped slaves. Key himself at one time owned seven slaves; he was also involved with efforts to end slavery, but not through abolition. As a founder of the American Colonization Society, Key promoted settling parts of West Africa with free and enslaved African Americans.

This sale marks the first time that a full issue of the September 20, 1814, Baltimore Patriot has gone up for auction, rather than an isolated clipping of the anthem. That larger context brings the contradiction of American history into stark focus: on page two, “the land of the free,” on page one, a refutation of that star-spangled sentiment.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook