In Thailand, Funeral Cookbooks Preserve Recipes and Memories

Though their origins are tragic, the books provide invaluable inspiration.

The memory of Thanaruek Laoraowirodge’s favorite Thai dish is intertwined with the memory of his grandmother, Somsri Chantra. Originally from the eastern town of Trad, Laoraowirodge vividly remembers the chicken stew that she would cook after he returned home from school.

The dish, as simple as it is, is included in his family’s upcoming cookbook, a volume that will detail the recipes created by his khun yai, or grandmother. Not surprisingly, Yai Somsri’s recipes also make up much of the menu for his family’s popular Bangkok eateries, Supanniga Eating Room and Krua Supanniga by Khunyai.

Laoraowirodge considers the upcoming tome to be the family’s first funeral cookbook. “It will include all stories of memories from our family members with khun yai, related to her life and her cooking,” he says.

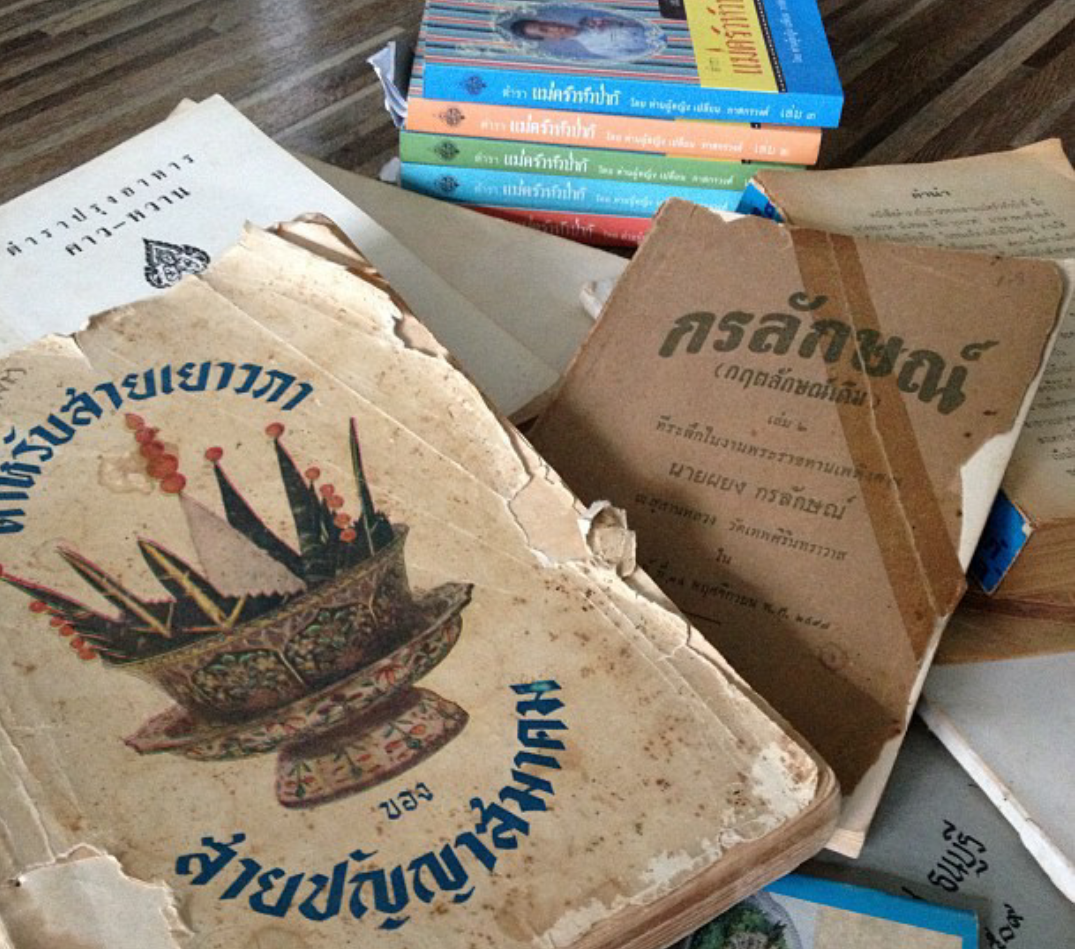

Most Thais consider funeral books a way to safeguard good memories of a loved one. Distributed by family members as mourners file into the temple to say their farewells, funeral books are typically put together by grieving children or partners. Often, they document the life of the deceased, share family anecdotes and photos, and reprint important Buddhist sermons.

However, many books cannot help but include matters dear to the departed’s heart. A jewelry aficionado’s funeral book could contain a primer on spotting gem quality. For an avid foodie, it might include their favorite places for street eats, replete with histories of the vendors. Yet whether a slim pamphlet or a thick, hardcover volume, favorite family recipes have become standard funeral book content.

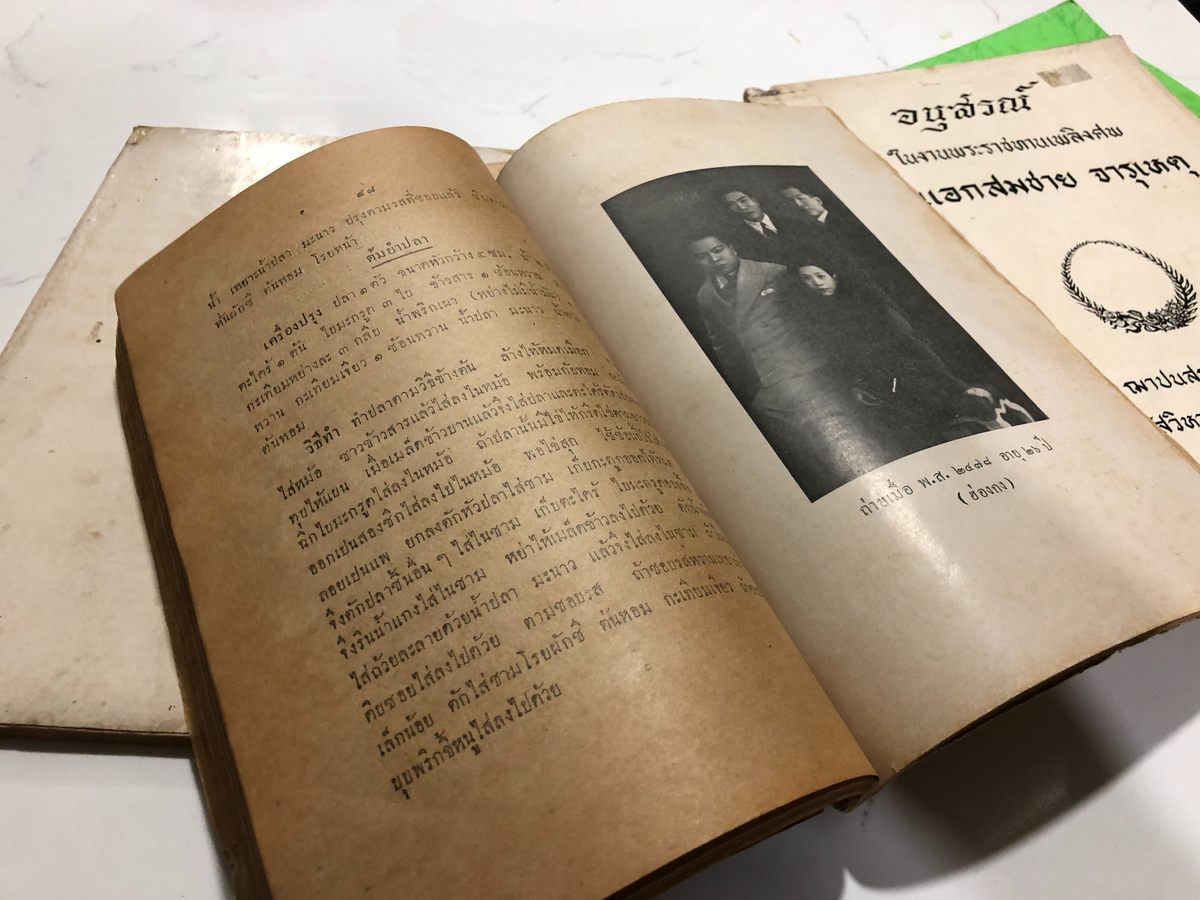

But legend has it that the origins of the Thai funeral book are rooted in tragedy. The first queen of King Rama V, Sunandha Kumariratana, and her daughter, Princess Karnabhorn Bejraratana, drowned in 1880 when their boat capsized on the way to the palace. Courtiers and servants who would have been able to help were rooted to the spot, for fear of breaking a law that forbade commoners from touching royals. At their funeral, King Rama V gave out 10,000 books to commemorate the lives of the queen and his daughter, but these did not include any recipes. Instead, they featured Buddhist teachings and philosophy. The nangsue anusorn ngan sop (funeral book) was born, and the custom was swiftly copied by the king’s subjects.

The motives behind this tradition, however, may not entirely stem from a desire to keep good memories of the deceased alive. “Grand families were very competitive in showing face—and still are,” says Phil Cornwel-Smith, author of Very Thai and the new book Very Bangkok. “Funeral books would have shown all the titles, awards, and ranks that the deceased had been bestowed, which would be of vital interest for the surviving relatives to publicize and justify their social position.”

While funeral books were initially considered the purview of the aristocratic elite, the bourgeois—the military, high-ranking civil servants, and wealthy merchants—were only a few steps behind. Initially, Buddhist philosophy was a popular feature, until King Rama V in 1904 proclaimed the volumes to be “not very enjoyable” and advised future books to include more interesting subject matter, such as popular Thai fables. It was only later, in the mid-20th century, when food-related matters became the norm in funeral publications.

“For grand ladies of the past, there would be far less in terms of rank to document,” says Cornwel-Smith, “so their household accomplishments would be lauded, such as recipes,” adding that one of his first jobs in Thailand was to edit a funeral booklet for a female Sino-Thai banker.

It might seem odd that Thailand would be able to nurture the unique culinary tradition of the “funeral cookbook” when cookbooks themselves were a relatively recent phenomenon. Inspired by Isabella Beeton’s The Book of Household Management, the first Thai food cookbook, Mae Khrua Hua Pa (or “Talented Women Chefs”), was published by Lady Plian Phasakorawong in 1908. Before Lady Plian’s masterwork, recipes were transmitted verbally, ideally to family or household members only. These recipes were guarded fiercely. For a family to reveal one’s culinary secrets was tantamount to ceding social cachet to another rival house. “Grand families competed in culture as much as in titles, such as quality of food and rival troupes of traditional musicians,” says Cornwel-Smith.

The publication of the first Thai cookbook finally allowed for the sharing of private culinary knowledge in the public sphere. It also reflected a general rise of literacy in the pursuit of siwalai, the Thai attempt to appear more “civilized” in the face of encroaching colonization, academics say.

The debut of Mae Khrua Hua Pa was said to have been a commercial failure because of its relatively high price. However, it has since managed to take hold of and eventually shape Thai culinary discourse—primarily through its reprinting as a souvenir for Thai funerals. In essence, it has enjoyed a second (and third, and fourth) life as a funeral cookbook for families wary of sharing their own recipes.

Other funeral cookbooks have added to the cultural conversation by keeping specific family traditions alive. The many funeral cookbooks of one of the grand houses of old Siam, the Bunnag family, detail a plethora of dishes from the homeland of Sheikh Ahmad, who arrived in the kingdom as a Persian merchant in 1600. After entering the service of King Songtham, Sheikh Ahmad eventually rose to the rank of samuha nayok (First Prime Minister), a position that many of his descendants would also hold.

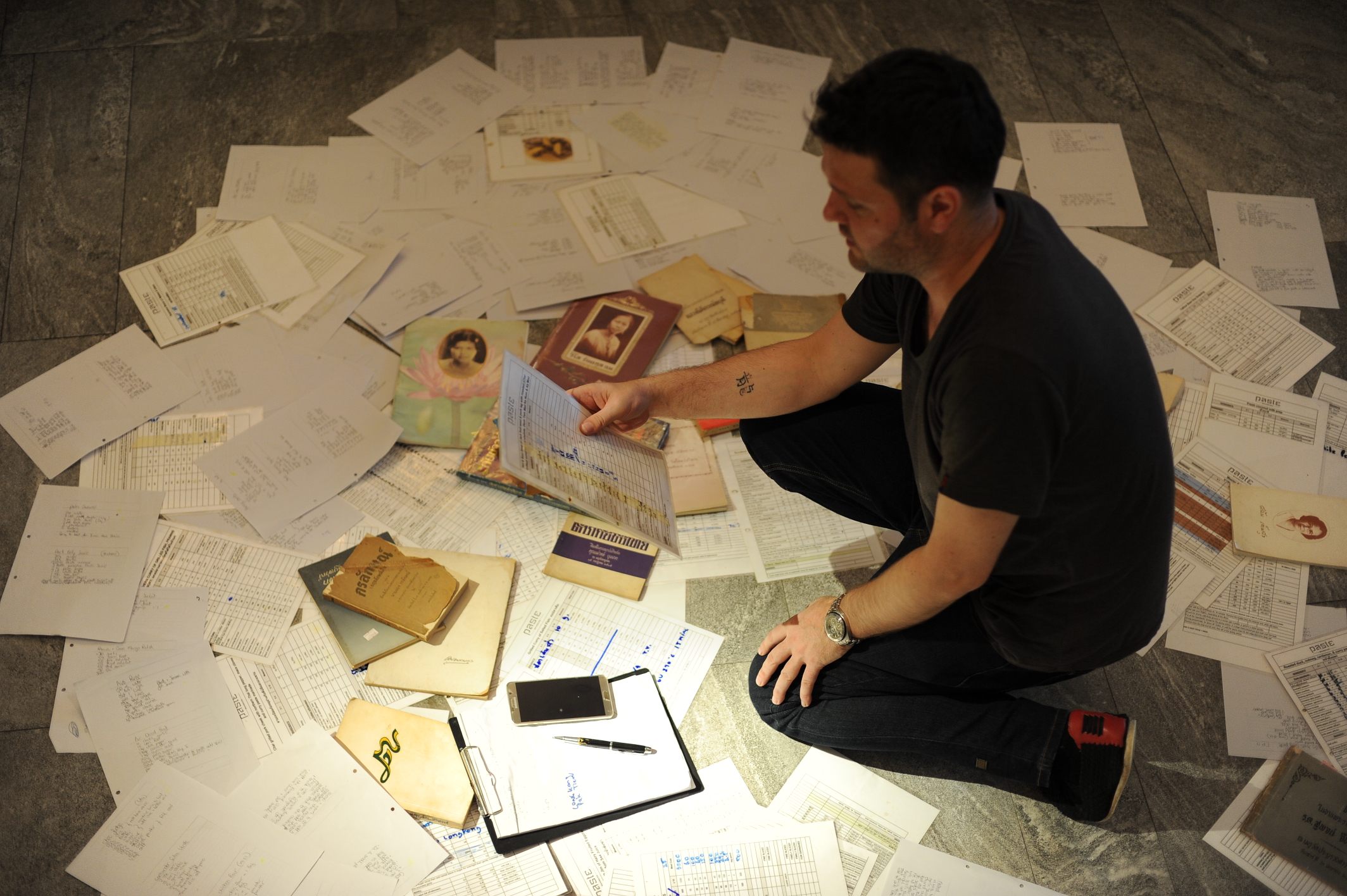

Scholars such as Thai food chef David Thompson—the proud collector of at least 600 funeral cookbooks—credit the Bunnag family for bringing gang massaman (loosely translated to “Muslim curry”) to Thailand. Although hailed today as one of the most popular Thai dishes in the world, massaman curry is still classified by some Thais as “foreign” since it incorporates a mix of dried spices, while traditional Thai curries are based on fresh herbs.

Today, the family recipe for massaman curry lives on in Bunnag funeral cookbooks, and includes raisins, small potatoes, nutmeg, cumin, star anise, cardamom, mace, and the decidedly un-Thai flourish of bay leaves. In the funeral cookbook of Sheikh Ahmad’s descendent Longlaliew Bunnag, one can find Persian-inspired gems such as the aforementioned massaman, khao buree (translated loosely as “smoked rice,” the family’s own take on chicken biryani) and sai gai, a saffron-scented, syrup-soaked dessert known as jalebi in Indian cuisine.

A wealthy family into the 20th century, the Bunnag family recipes also mirror the many foreign influences that shaped the Thai upper classes. One recipe calls simply for Chinese-style egg noodles mixed with olive oil and sprinkled with “the grated cheese of your choice,” a fusion that probably would have horrified Lady Plian.

In an essay on Thailand’s culinary identity, journalist Panu Wongcha-um argues that funeral cookbooks are still shaping Thai culinary discourse. This can be amply illustrated by the menus of Michelin-starred Thai restaurants such as Nahm, Paste, and Bo.lan, whose menus are rooted in the funeral cookbooks of noble families and whose chefs are celebrities in their own right.

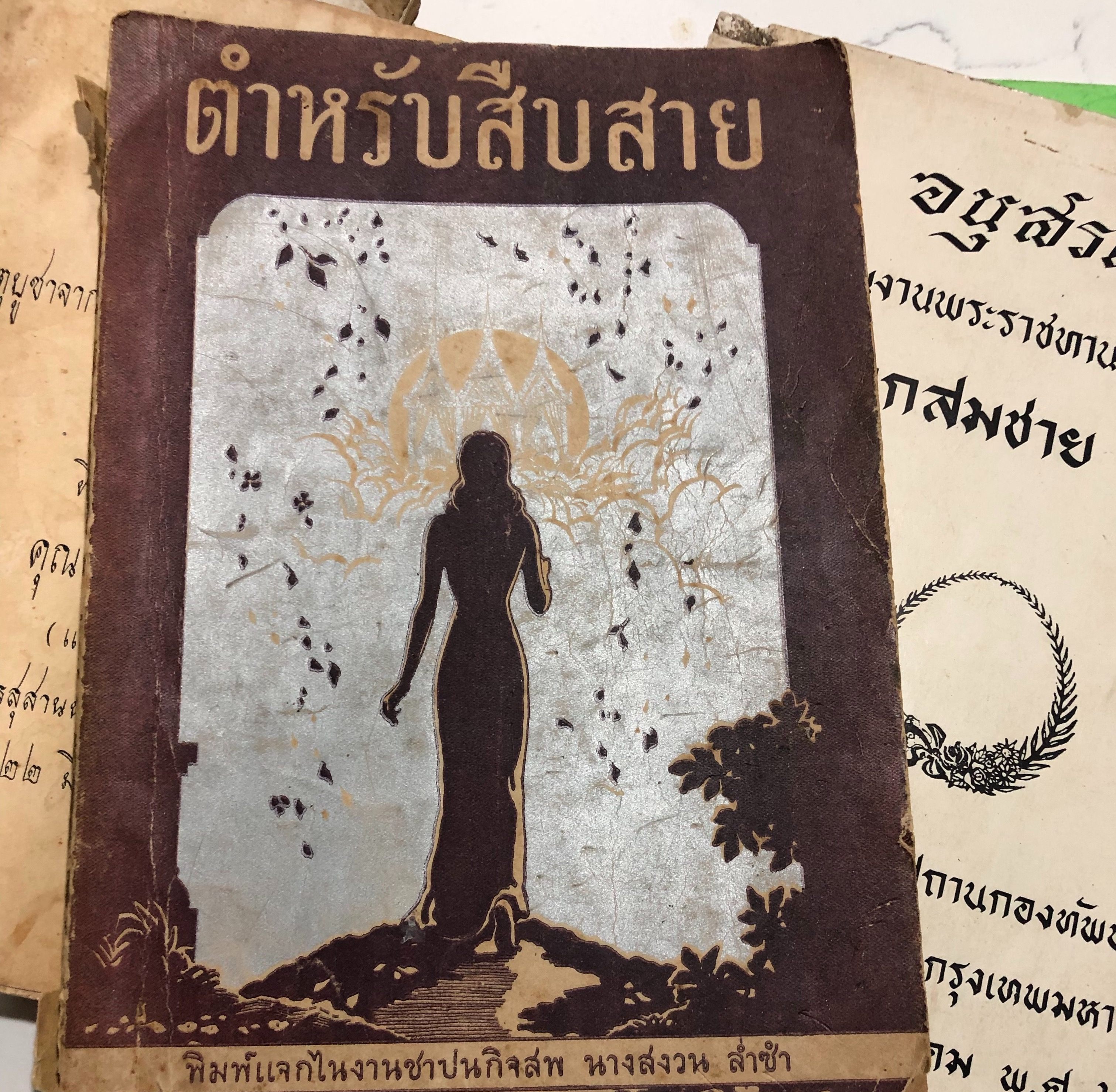

Chef Bo Songvisava, like her former boss David Thompson, has a sizable funeral cookbook collection of her own. Besides inspiring her cooking, the funeral cookbooks in Songvisava’s collection represent the achievements of Thai women in the only sphere once permitted to them: the home.

“Funeral books with recipes in them in the early years mostly belonged to ladies from noble families,” says Songvisava, who is in the midst of writing her own cookbook. “Printing merely a cookbook must have seemed ridiculous back then, so they used funerals as an occasion to respect the deceased and pass on her skills, knowledge, and legacy.”

Chef Jason Bailey of Paste estimates that he and his wife, fellow chef Bee Satongun, have collected several hundred funeral cookbooks. The books, while providing a snapshot of a certain time, were also helpful in showing how Thai cuisine has evolved. “We were interested in seeing how they riffed and adapted Thai recipes,” he says of past cooks.

Ultimately, the Thai funeral cookbook was born in a hothouse environment of its own, fed by royal encouragement, the threat of colonization, a dearth of spaces for female expression, and the gradual literacy of the masses. However, unlike many conventions of the past, the funeral cookbook thrives today, even popping up abroad. British food writer Alan Davidson was so charmed by the idea that he compiled a 47-page booklet of his own, to be distributed at his 2003 service. The volume included recipes for personal favorites, such as meatloaf and toad-in-the-hole.

Songvisava thinks her funeral cookbook would highlight her work at her restaurant. “The recipes that I will include in my funeral book will be the ones that are served in Bo.lan and Bo.lan only,” she says, singling out green curry with local green figs, a salad of fresh northern Thai greens adorned with grilled fish, and household essentials such as Sriracha sauce.

Her husband, co-chef Dylan Jones, says he would present a mix of Thai influences and his Australian heritage in his funeral cookbook. For him, that means two particular recipes: one for nam prik prik Thai oorn, or black pepper chili relish, and another for Vegemite on toast.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook