An 1888 Road Trip Sparked Germany’s Romance With Cars

But now diesel models, at least, could be banned in city centers.

Stuttgart, Germany, is a car town. The car company Daimler, which owns Mercedez-Benz, has its headquarters here. The first practical car—which debuted at the World’s Fair in 1889, almost two decades before the Model T went into production—was invented less than a two hour’s drive from here.

It’s also one of the most polluted cities in Germany, which is why an environmental rights group, Deutsche Umwelthilfe, took legal action to force Stuttgart and other cities to meet European Union air quality standards. In some cases, the group argued, the only way to meet those standards would be to ban diesel vehicles from city centers altogether.

While governments fought back, this week a German court found that the proposed bans on diesel cars were legal. Soon the streets of one of the auto industry’s most important cities could be relatively free of cars.

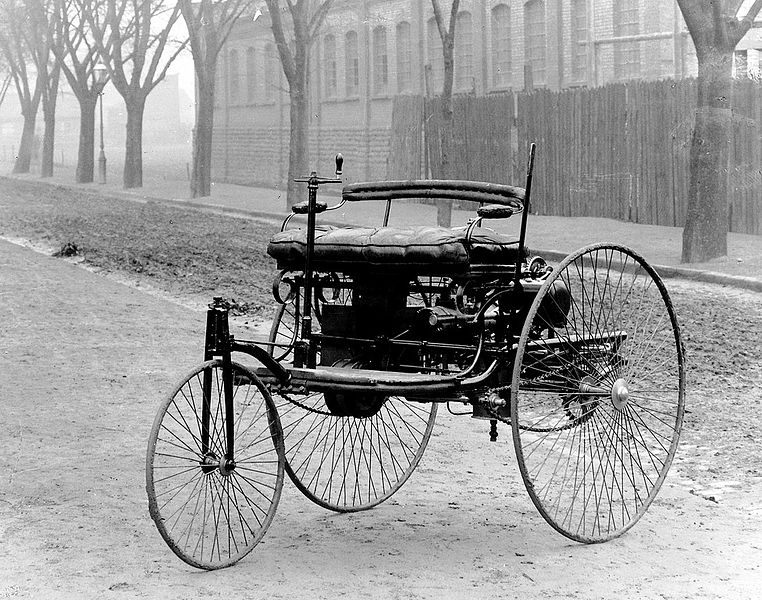

Germany’s love for the automobile began with a road trip from nearby Mannheim to the town of Pforzheim, less than 30 miles from Stuttgart. In 1885, Karl Benz had invented his first Motorwagen, a three-wheeled vehicle with a gas-powered engine of his own design. One of the first times he managed to get it started, he drove it straight into his laboratory wall.

By 1888, he had a working prototype, which had successfully driven down a road. The now-patented Motorwagen had no gears and could not go up hills, but it worked. One morning, Benz’s wife Bertha decided to take the car on its first extended road trip. With her two sons, she pushed the car out of the garage, until it was far enough from the house that they could get it started without waking her husband.

Bertha Benz had a destination in mind—her parents’ house in Pforzheim, about 65 miles from her home. Following roads meant for wagons, she and her sons started the drive—the first recorded road trip in a car.

There were challenges. A pipe clogged; Benz cleaned it with her hat pin. A wire shorted; she insulated it with her garter. They needed more fuel; she convinced a pharmacist to sell her an unusually large amount of the gas the car used. When the brakes started wearing out, she had them shod with leather at a cobbler. When she reached a hill, she had the boys push (along with local help).

By the end of the day, the Benzes had reached Pforzheim, where Bertha telegraphed her husband that they were safe. After a few days’ visit, they drove back home to Mannheim.

Ten years ago, Germany created an official Bertha Benz Memorial Route, marking her historic road trip. Part of Bertha Benz’s motivation was to sell potential customers on the advantage of automobiles; although it took another decade or so, people eventually bought into this transportation revolution.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook