The Mischievous ‘Ghost Hoaxers’ of 19th-Century Australia

To stave off boredom, some people donned sheets and menaced the public.

In 1882, in the southeast Australian state of Victoria, repeated attacks on the general public were carried out by a figure known only as the “Wizard Bombardier.”

This individual was known for wearing an ostentatious outfit of white robes and a sugarloaf hat. The Wizard’s strategy involved disorienting people with loud screams before hurling stones and other sorts of missiles at them. Then the ghoulish individual made a quick dash and was gone.

Attacks like these, in which pranksters disguised as ghosts would wreak havoc, came to be known as “ghost hoaxing.” There were many cases and perpetrators in Australia from the late 19th century to the First World War—to the point that rewards were offered for the apprehension of ghost hoaxers.

In this era, Australia was the perfect location for villains and rogues who wished to imitate apparitions for their own ends. David Waldron, author of the article “Playing the Ghost: Ghost Hoaxing and Supernaturalism in Late Nineteenth-Century Victoria,” says that the lack of professionalized police meant that Australia had a particular “lawlessness.” That, along with an abundance of leisure time and a lack of affordable entertainment options, created an environment ideal for ghost hoaxers, who often used their own theatrics to entertain themselves.

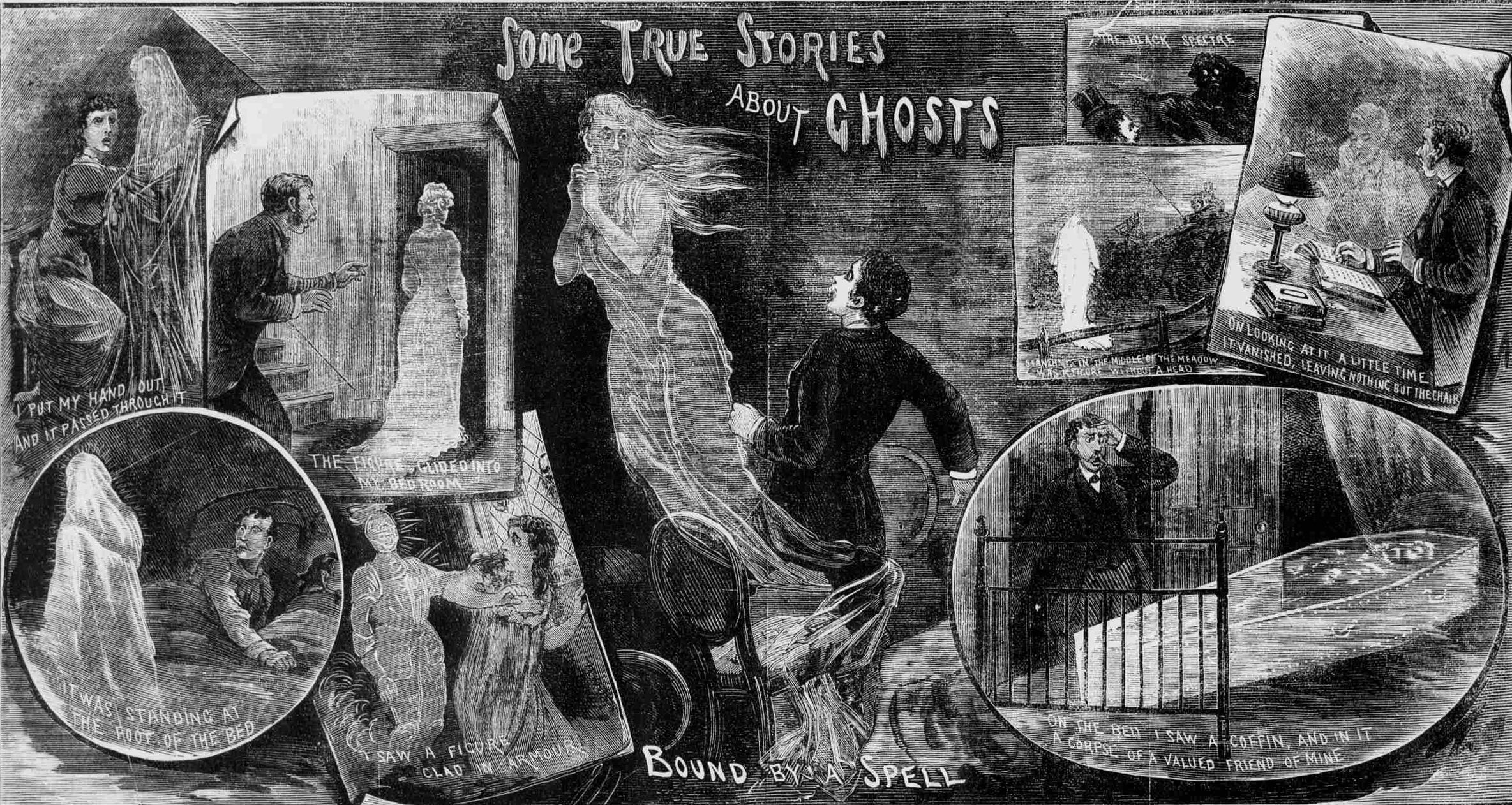

Technology helped make the ghost pranksters look spooky. As Waldron writes, the recent invention of phosphorescent paint meant that individuals could glow in the dark as they menaced others, which made their outfits all the more believable and gave them an otherworldly appearance. Ghost hoaxers sometimes fashioned elaborate disguises: In 1895, for instance, one prankster created a costume to resemble a knight and emblazoned the phrase “prepare to meet thy doom” on his armor. To ratchet up the threat factor, this “knight” also threatened people with decapitation.

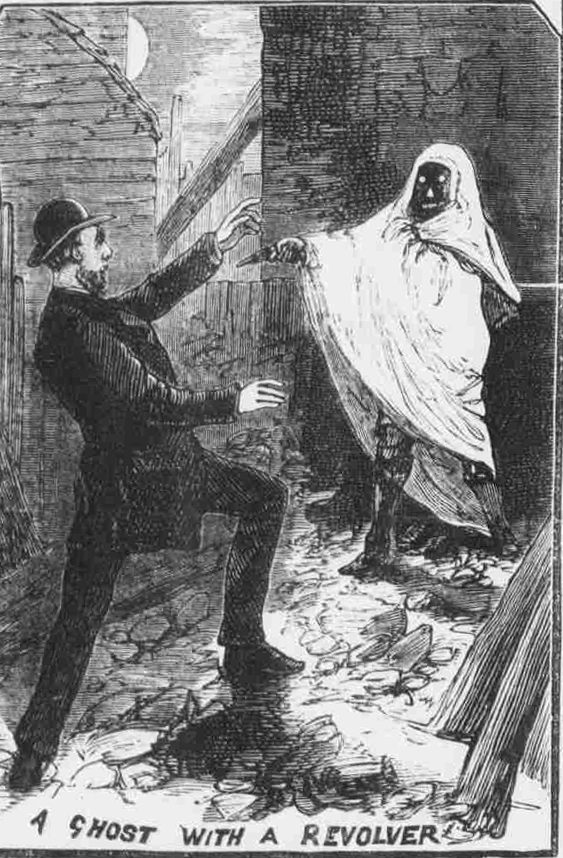

Australia during this period was very concerned about the threat of “larrikins”—rowdy youths out to cause mischief. Some of these larrikins regarded ghost costumes as suitable devices with which to commit crimes and violence. A sort of urban warfare was fought, with ghost hoaxers on one side and, on the other, vigilantes and armed guards determined to shoot the pranksters with buckshot, as a way to end their mischief.

Waldron writes that despite the ghost pranks being associated with the working class, once the ghosts were apprehended, “many if not most of those arrested” were in fact “school teachers and clerks and the like and a small number of middle-class women.”

One unexpected ghost hoaxer was Herbert Patrick McLennan, who in 1904 equipped himself with a glowing outfit that included a top hat, frock coat, and boots. Most menacingly, McLennan carried a cat o’nine tails whip and used it to assault women he encountered. When a bounty of £5 was placed on McLennan, he proceeded to declare war on the authorities, threatening to shoot anyone who came after him in a letter addressed to local leaders, in which he referred to himself as “the ghost.” When McLennan was arrested, however, he turned out to be a powerful, influential clerk and public speaker. McLennan was sent to jail, but he was soon back out again.

Some ghost hoaxers made their own custom disguises—such as wearing a coffin strapped to their backs, so as to give the appearance of having risen from the dead, as in one case in 1895. A female ghost hoaxer even incorporated music by playing a guitar while she skulked around near a hotel, according to reports in 1880 and 1889.

One theme common to ghost hoaxers was the use of pre-existing superstitions and locations that were regarded as haunted or associated with death, such as cemeteries, in order to double down on fear. Some hoaxers even painted a skull and crossbones in a particular location, to create a sense of fear before they arrived to wreak havoc.

To the wider community, ghost hoaxers presented a threat not just through fear but also via crime and violence, such as indecent exposure, sexual assault, or even just egg theft. Not all citizens were prepared to stay helpless in the face of this threat. In 1896, an ex-soldier named Charles Horman seemed to be a one-man army against the spectral impersonators. He opened fire with a shotgun on one youth who was pretending to be a ghost, while using a cane to attack another hoaxer who was assaulting a woman.

Parents whose children had been physically attacked by ghost hoaxers also took the law into their own hands. One woman unleashed her pit bull on a hoaxer who had assaulted her daughter. In 1913 a mob of vigilantes chased and beat a man wearing a glowing ghost outfit who had terrified an old man.

Eventually, the phenomenon of ghost hoaxers ended, hastened by the arrival of World War I, which took the lives of over 60,000 Australian soldiers. As Waldron says, the war showed that there were “far bigger issues at stake, and the symbolism of death [became] less amusing.” With human mortality no longer a premise for pranks, ghost hoaxers lost their spirit for good.

This story originally appeared on August 2, 2017.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook