Half a Billion Years Ago, These ‘Terror Beasts’ Ruled the Seas

Spoiler alert: They’re giant worms.

Take a ride on the way, way, way back machine to about 520 million years ago. The Cambrian Explosion—Earth’s biggest bang of biodiversity, when the variety of living things increased exponentially—was just wrapping up. Terrestrial plants and animals had not yet evolved so the land was still barren, but oceans teemed with life. Early arthropods, invertebrates with tough exoskeletons, were becoming fierce predators.

Now meet the terror beasts who ate arthropods for breakfast (and lunch and dinner).

Paleontologists working in Peary Land, the northernmost edge of Greenland, have found fossils of an extraordinary animal previously unknown to science: a giant predatory worm, equipped with large jaws, that they named Timorebestia, or “terror beast.” One of the 13 specimens found at the site had a small arthropod still in its maw; several other specimens had arthropods in their digestive systems, suggesting Timorebestia was one of the world’s earliest (and best-equipped) predators.

As for its giant size, well, everything’s relative. The largest specimen was nearly a foot long, which may not sound impressive until you consider that most animals during this period were well under an inch.

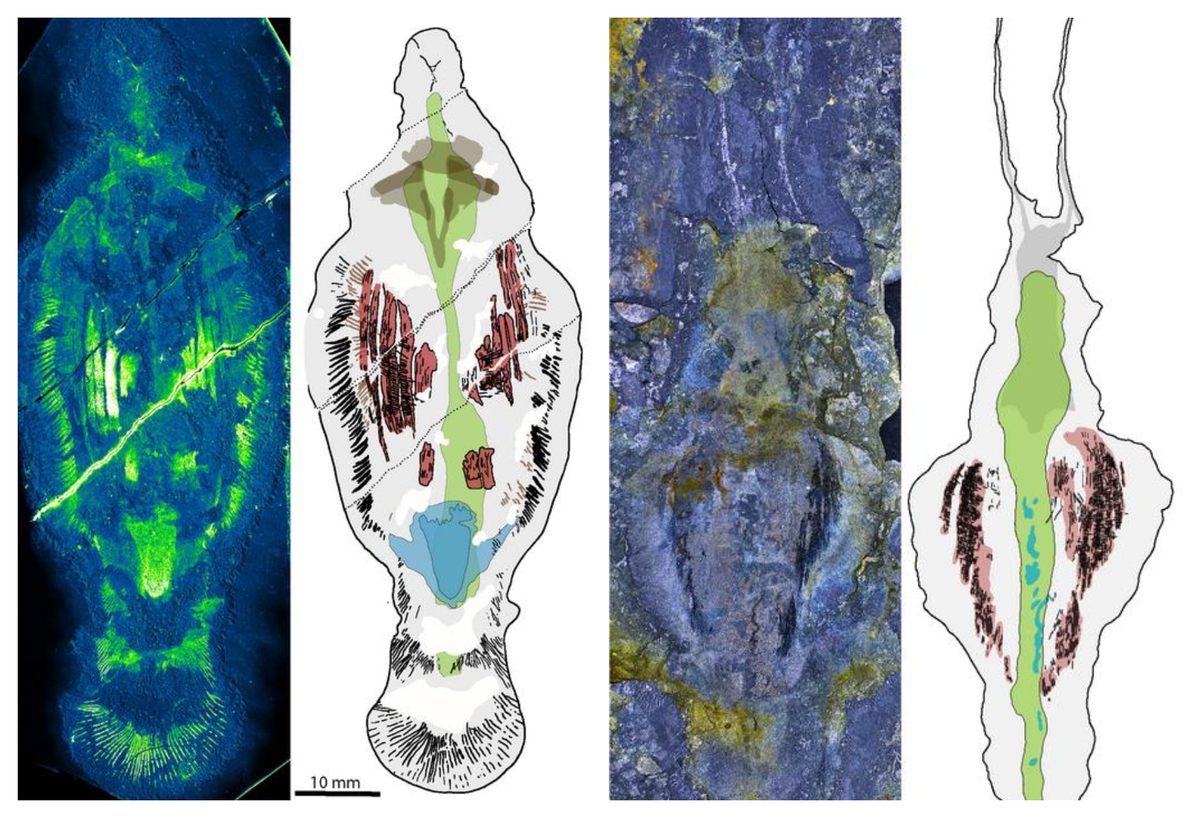

While fossilization typically preserves bones and very occasionally skin, the team was able to tease out additional details about the species by using an electron probe microanalyzer (EPMA) to essentially map carbon signatures preserved in the specimens. The EPMA revealed fins running down most of the length of the body, long antennae, and even some of the musculature and nervous system.

Timorebestia is related to today’s arrow worms, a group of marine animals known to be “strongly carnivorous.” Modern arrow worms are considerably smaller than the Cambrian beast, however, and have evolved external, spiky bristles to catch prey instead of the formidable jaws of their ancient relative, making them somewhat less impressive.

Paleontologists were able to determine Timorebestia was related to today’s arrow worms, also known as chaetognaths, in part because the ancient animal has an anatomical feature unique to this phylum. All chaetognaths have a distinct structure in their midsection that’s part of their nervous system. This so-called ventral ganglion plays a role in the animals’ sense of touch, and in how they move through the water. Timorebestia’s ventral ganglion is particularly large relative to its body size; together with its well-developed fins, it suggests the ancient predator may have been a particularly efficient swimmer and successful predator, the Jaws of its Cambrian day.

The terror beast’s reign did not last, however. In the wake of the Cambrian Explosion, arthropods in particular continued to diversify and get bigger. By about 515 million years ago, they included the shrimp-like predator Anomalocaris, which may have reached lengths of three feet or more. According to a study published in 2023, Anomalocaris preferred soft prey, just like Timorebestia—perhaps one reason the terror beast vanished from the fossil record.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook