New York’s Insatiable Appetite for Truly Enormous Oysters

A massive mollusk recently found in the Hudson River is the latest example of two centuries of appreciating behemoth bivalves.

The year 1903 was a bad one for oysters—or, rather, it was an unsavory time for the New York gourmands who craved heaping piles of goodly mollusks. In February of that year, from his float at the base of Gansevoort Street, which runs straight to the Hudson River, one anonymous exporter lamented that the oysters were so spotty and small that “it is scarcely worth bringing them to market.” Succulent large ones, or even acceptably average contenders? Those, he said, “are as scarce as grapes in Greenland.”

And the little ones were not going to get much play in the city’s seafood bars. “New York does not like the small oyster,” the exporter continued. Restaurants and hotels demanded mollusks with a theatrical streak, “that would make a show in a fry, or panned, or stewed.”

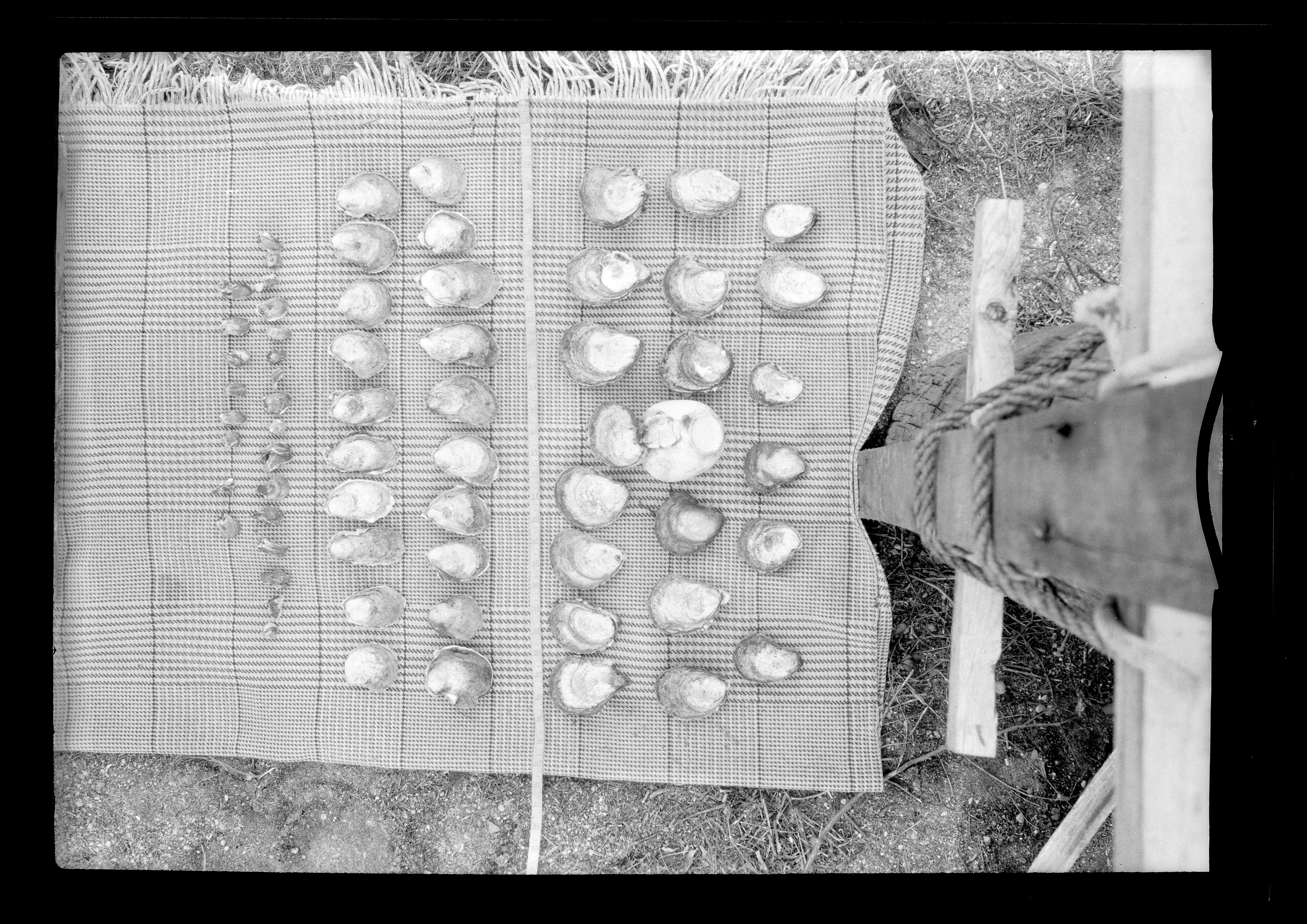

As the 19th century rolled into the 20th, New York newspapers were full of dispatches about oysters—enormous ones in particular. One described bivalves that washed ashore in Australia, measuring more than a foot across the shell. Another reported that one had turned up on the banks of Christchurch, on England’s southern coast, weighing in at 3.5 pounds.

For a time in the 1800s, the city drooled over Saddle Rock oysters—a splendid, sizable variety that carried with it a whiff of myth. (They were said to be named for their home, an equestrian-shaped rock in in the East River, where a bed was revealed during low tide one day in 1827.) Though this crop was exhausted soon after, the name lived on, and was attached to many large varieties. Just how big New York’s biggest oysters usually were, though, remains as murky as a sediment-swirled river. “New York oysters, like so much in New York, were not really bigger, just better marketed,” wrote Mark Kurlansky, author of The Big Oyster: History on the Half Shell, in the New York Times. Meanwhile, the Bluepoint oyster—the mild-mannered species Kurlansky has described as the state’s most famous—isn’t all that big.

Two centuries ago, oysters were so wildly abundant that they weren’t treated as luxury foodstuffs. But soon the city’s bottomless appetite for them—combined with pollution and dredging—resulted in the near-extinction of oysters in the city’s waterways. In recent years, however, the mollusks have started to return. For the most part, they’ve been coaxed along as part of environmental remediation projects—the filter-feeders can help form the foundation of a healthy habitat.

Last week, a construction crew working on a set of pilings on Pier 40, in Manhattan, happened across a truly massive specimen. They brought the 8.6-inch-long oyster to the River Project, a research and education group focused on the Hudson River. “It was the biggest oyster I’d ever seen,” says Toland Kister, an educator at the River Project. It visibly dwarfed any oyster you might see in a restaurant, and it maxed out the group’s triple-beam scales, which go up to 610 grams (roughly 1.3 pounds).

Also, it was still alive.

At first, Kister says, the team was worried about it—a large, old creature wrenched from the place where it was settled. But it spent the weekend in one of their flow-through tanks, which hold river water. Then, on Monday, it was returned to the water—this time, suspended in a cage.

There’s a lot left to learn about the find. Like trees, oysters carry growth rings that enumerate the chapters of their lives, but these are somewhat unreliable narrators. Since they’re affected by food scarcity and stress, the exact age of the found is unknown. A conservative estimate puts it somewhere around seven or eight years old, Kister says, and some people suspect it’s closer to 15. That would make it positively ancient among local mollusks.

Was the oyster all alone on its piling? “We don’t know the exact situation down there yet,” Kister says. “This one could be incredibly unique—it could be the only one like it, or it could be part of a group.” The only way to know for sure will be to go inside the construction zone, and Kister is working to learn about what the crew is seeing.

As far as anyone can tell, no one is planning to attempt to swallow this briny beast—but its presence in the local waterways is promising for the future of these urban estuaries, if not exactly a harbinger of a return to New York’s rapacious past.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook