The Farming Colony That Grew Under the Midnight Sun

How the New Deal seeded giant vegetables in Alaska.

Each year, both locals and tourists from around the world crowd into the farm exhibit building at the Alaska State Fair in Palmer to get a look at cabbages the size of huskies, carrots so big they seem otherworldly, and pumpkins that must be lifted by a small crane.

With its fertile soil and summer days boasting close to 20 hours of sun, this region of Alaska, including Palmer’s Matanuska Valley, has garnered a reputation for producing huge, record-setting vegetables: a 138-pound cabbage, a 2,051-pound pumpkin, a 64-pound carrot.

Encircled by snow-capped peaks and criss-crossed by bears and moose, the valley is a study in the improbable becoming probable. Thousand-pound pumpkins are more curiosity than crop, and many of the largest vegetables are donated to the Alaska Wildlife Conservation Center in Girdwood as food for bears, bison, and caribou after the fair is over. Whether for food or competition, however, farmers here harvest remarkable yields of fruit and vegetables, and they have been ever since the administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt organized an experimental farm colony in the valley during the Great Depression.

In the 1930s, farmers across the United States struggled to survive in the midst of drought and financial devastation. With the New Deal’s rural rehabilitation program, Roosevelt’s administration tried anything it could to help, including resettlement projects like the Matanuska Colony.

But unlike other resettlement projects, which were typically situated near needy communities with existing infrastructure, the Matanuska Colony, off the road system and more than a thousand miles north of Seattle, might as well have been located on another planet. Creating the Colony was perhaps more a strategic decision than a practical one: It would help farmers start a new life, but also allow the United States to expand its presence in the remote, sparsely populated territory.

The Resettlement Administration chose farmers from Michigan, Minnesota, and Wisconsin—the climate in those states was most similar to Alaska’s, and intensive logging practices had depleted their soil. Arthur and Mabel Hack, for instance, had, like many others, been barely getting by in Ogilvie, Minnesota, with their three children when they got word of the new Alaskan Colony. They, along with more than 200 other families, applied, drawn by the promise of a new start in the Far North.

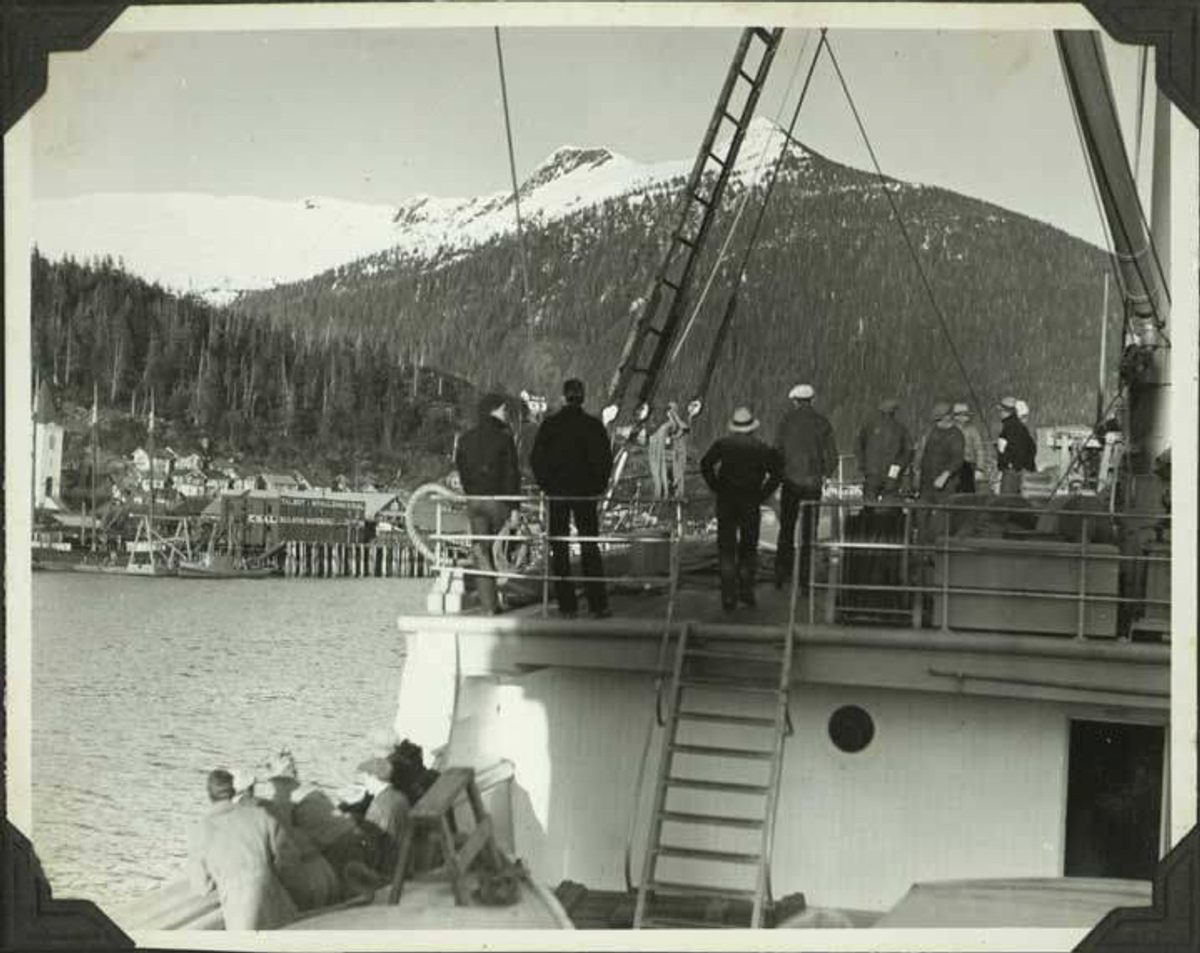

In May 1935, the chosen families traveled by train and ship to the territory. Each received a 40-acre tract of land, farm equipment, and a house—built by transient workers hired for the project with the help of the farmers themselves—all courtesy of loans from the federal government.

For centuries, the Matanuska Valley had been hunting and fishing land for the native Dena’ina and Ahtna Athabaskan peoples. But over time, non-native homesteaders, farmers, and miners, who had come and gone through the years since Alaska became a U.S. territory in 1867, forced them off their land. The Matanuska Colony, however, was the first large-scale effort to create a farming community in the valley.

Once they arrived, the families moved into hastily erected tents in Palmer. While they waited for supplies, they drew their tracts of land. Arthur Hack drew the first tract, and it took some time and trading between colonists before all of the land was spoken for.

Farming in Alaska, however, proved difficult. The farmers needed to clear their land, plow the rocky soil, and adapt to an unfamiliar, harsh climate. They struggled with the extremely short growing season, illness, and short supplies.

Still, there were signs of hope. The Colony saw the birth of its first baby in July, 1935, to Howard and Bernice Van Wormer, who were originally from South Boardman, Michigan. By the next summer, the farmers were harvesting potatoes, cauliflower, cabbage, radishes, spinach, and other cool-weather crops that they found thrived in the valley.

Given the difficulties they faced, many of the original colonists left within several years. By 1965, only 20 of the original families remained. Yet the Matanuska Valley Colony succeeded in establishing the community of Palmer and a tradition of experimenting with far northern farming techniques that continues to this day.

“The colony transformed the area,” says Sam Dinges, executive director of the Palmer Museum of History and Art. “Palmer was an agricultural colony, and there’s really not another story like that in Alaska.”

The Matanuska Colony farmers found that though the region’s winters were cold and harsh, its long summer days and mineral-rich, glacial soil helped them to grow large cabbages, pumpkins, beets, and spinach quickly—sometimes seemingly overnight.

“When people started growing large vegetables here, they found that the good soil and long daylight hours helped them to succeed,” says Dinges. “It’s a point of pride for the area to have the right geographic and geological conditions that allow for that.”

Ellen Vande Visse, owner of the Good Earth Garden School and an original Colony house, who tills land farmed by colonists like the Hacks, concurs that growing food in the valley is a unique and rewarding experience.

“The long days make up for a lot of the short season and cool soils,” says Vande Visse. “It’s short, but what a burst that long daylight is.”

Living on Colony land is a constant reminder of those who came before, and Vande Visse sees evidence of that history all around her.

“They had one summer to clear land, build their house, and get enough wood for winter,” she says. “A lot of things formed in Palmer were built on cooperation. There was a need for a library, so people came together to make that happen. The Matanuska Electric Association was built as a cooperative. There’s a sense of groundedness, of people helping each other out.”

Farmers who have succeeded in the valley have done so by adapting to the realities of the far northern climate. Some have developed new varieties of vegetables and fruits, such as local farmer Bruce Bush’s peanut potato, which is still a popular item at Bushes Bunches Produce Stand in Palmer. Farmers here have also learned to make the most of the short growing season by using an extensive network of greenhouses, hoop houses, high tunnels, and other inventive strategies. Productive farming in the region is a constant work-in-progress, but for those willing to take on its challenges, the valley still has much to offer.

“The growth patterns here are extraordinary,” says Zoe Fuller, owner of Singing Nettle Farm in Palmer and part of a generation of younger farmers in the Matanuska Valley. “I went to a friend’s wedding for two days. It rained, and there was beautiful sunshine for 20 hours a day, and I came back and the vegetables were noticeably larger. It’s remarkable how quickly it happens.”

As the climate changes, farming in Alaska could well change—with seasons potentially shifting and new pests arriving. Land and water are both at a premium in the valley, as the population increases and farmland is threatened by encroaching subdivisions. Still, agriculture is flourishing in the valley, which has given rise to a number of small-scale, intensive, and innovative farms.

“A lot of our farms are hand-worked or modestly machine-worked, so there’s a lot of human input and intensive farming, with specialty crops on small pieces of land,” says Jodie Anderson, who manages the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Matanuska Experiment Farm and Extension Center in Palmer. “That’s unique to the success of Alaska farms.”

While not everyone in the area aims to grow monster vegetables, those who do will continue to find a rapt audience for their cabbages, pumpkins, leeks, and carrots at the Alaska State Fair. These farmers work hard to grow their huge vegetables, using seeds specially bred for the purpose and carefully nurturing the produce from start to finish.

“Those giants are not a fluke,” says Kathy Liska, crop superintendent and horticulture manager for the fair. “It takes time and dedication to grow a vegetable like that, particularly with cabbages and pumpkins. They become part of the family.”

The vegetables, in turn, draw crowds of people curious about what can and does grow in this remote northern environment.

“We get visitors from all over the world,” says Liska. “I start getting calls in the early summer, and a lot of these are farmers from the Midwest and other places. To come to Alaska and see giant veggies is on their bucket list. They’ve heard about it, and they need to see it.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook