The Great Oxford Poop Prank

Don’t you guano know what happened?

Every day leading up to April 1, we’re telling the story of one ridiculous historic prank. Find more here.

William Buckland always loved poop. Over the course of his long and accomplished life, the 19th-century polymath discovered that so-called “bezoars,” coveted by natural historians for their beautiful shapes, were actually fossilized feces. Once, he visited a European cathedral famous for the puddle of “martyr’s blood” that continually gathered on its floor. He kneeled down, licked the liquid, and confidently deemed it to be bat excrement. Plus, he did his darndest to eat every type of animal under the sun, which likely made his own lavatory experiences fascinating.

Now that you know this, it should make sense that Buckland was an early adopter of guano as fertilizer, and that he immediately used it to pull off a devilish prank.

Guano–aka seabird poop—is full of nitrogen, phosphate, and potassium, three chemicals that help plants grow. Although South Americans had already been using guano to amp up their soil for centuries, word of this miraculous material didn’t reach Britain until about 1804, when the Prussian geographer Alexander Von Humboldt spread the word about it after his travels to Peru.

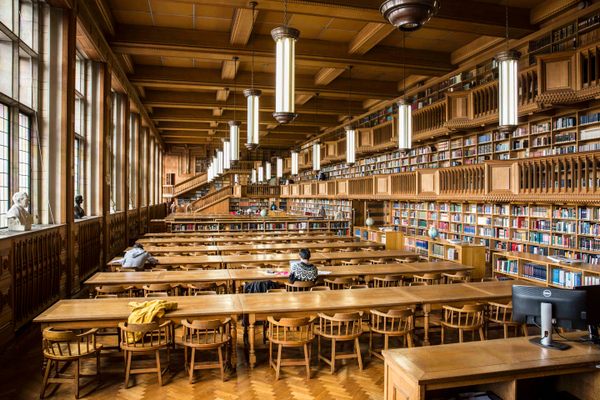

Although no one knows the exact year, it must have been around that time that Buckland, then a student at Oxford, managed to get his hands on some guano. He became so curious about its properties that he decided to test it out on the grass on Tom Quad, the massive lawn that spreads out in front of the main entrance of Christ Church, one of the colleges at Oxford.

Sure, he could have put a discrete pile in one corner of the grass to see what happened, but then no one else would be privy to the experiment. So instead, he decided to use the guano to send a message. It’s easy to imagine him in the dead of night, carefully spelling out five large letters.

It worked like a charm. “In due course the brilliant green grass of the letters amply testified to [guano’s] efficacy as a dressing,” reports Buckland’s biographer. In other words, it’s possible that the authorities quickly cleaned up the poop itself. But come springtime, when students, faculty, and clergy walked the path across the quad toward the stately reaches of Tom Tower, they were greeted by a big green message: GUANO.

Fast forward a couple of decades, and guano was all the rage across Europe. Buckland had racked up several titles, from Fellow of the Royal Society to Dean of Westminster Abbey—and a new, more uniform carpet of grass had doubtlessly come up on Tom Quad. But I’m willing to bet that verdant GUANO was engraved forever in the minds of all who saw it.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook