Happy 48th Anniversary, Here’s A Microscope!

How tradition, jewel lobbies, and fed-up librarians joined forces to tell us what to buy our spouses.

Or you could always get your wife a dead chicken. (Image: Gabriël Metsu/Public Domain)

This past December, Ellen Degeneres asked comedian Andy Samberg how he and his wife, harpist Joanna Newsom, celebrate their wedding anniversaries. “We do the thing, with the gifts, where there’s the thing it has to be made of for the year,” Samberg told Degeneres. “First year was paper, second year was cotton. Cotton, I got her a Grandma Got Run Over By A Reindeer Sweatshirt, and paper, I wrote on a piece of paper, ‘We can buy that table you wanted.’”

Most people know of of the general anniversary gift tradition (the crowd went wild at Samberg’s joke) but fewer are aware that there are a number of lists, each with their own variations, peculiarities, and deep cuts, and shaped equally by tradition, commercialism, and the wiles of public librarians. Where did they all come from? Which are real, and which are made up? And, most importantly, do any couples actually use them?

“There are only eight ‘true’ traditional anniversary gifts,” stressed the Chicago Public Library Information Desk in an email. These eight make a certain amount of hierarchical sense—paper comes in the first year, followed by wood in the fifth and tin in the tenth. After this, you level up quickly through crystal (15), china (20), and silver (25), before taking a long break and building toward gold (50). Diamond nabs the top spot at 60 years. After that, presumably, you’d be worrying about other things.

Queen Victoria, decked out for her Diamond Jubilee in 1897. (Image: W&D. Downey/Public Domain)

All of these materials have some grounding in (relative) historical precedent—under German tradition, for example, brides were given silver and gold myrtle wreaths when they reached milestone anniversaries, and Queen Victoria invented the Diamond Jubilee in 1897, to mark sixty years on the throne. In 1922, Emily Post gathered these traditions up in her Blue Book of Social Usage, calling them “eight anniversaries known to all,” though even she specified that “the paper, wooden and tin wedding presents are seldom anything but jokes.”

Fifteen years later, seeing an opportunity, the American National Retail Jewelers Association, a trade organization for jewelers, watchmakers, and salespeople, began working on a more comprehensive list of suggested anniversary gifts. This group was fresh off a recent triumph: In 1912, they had revamped the traditional birthstone list, filling it with slightly more expensive suggestions—pearls instead of cat’s eyes, sapphires over lapis lazuli. It worked like a charm. The years following saw similar PR coups, including a successful campaign to convince women that it was embarrassing to wear “winter gems” in summer.

According to news clippings from that time, other industries fought hard to get on the new Jewelers Association list. Appliance manufacturers tried to unseat “wood” at year five, but were stymied by the furniture industry and ended up at number eight. But the real winner was once again the jewelers themselves, who stacked the list with leather, silk, and other materials they were well-suited to provide.

Mrs. Rogers celebrates her golden wedding anniversary in a Gobowen Orthopedic Hospital in Wales, in 1954 (Mr. Rogers is out of frame). (Photo: Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru/CC0)

The next semi-official list—the one now excerpted on Wikipedia, Hallmark.com, and other sources—didn’t show up until the 1990s. According to the Chicago Public Library, this one was made by and for librarians, who, as the Wikipedia equivalents of the time, found themselves fielding a number of phone calls from distressed husbands and wives. Eventually, the librarians got together, pored over some etiquette guides and encyclopedias, thought about their own lives, and put together two different lists: “Traditional” and “Modern.”

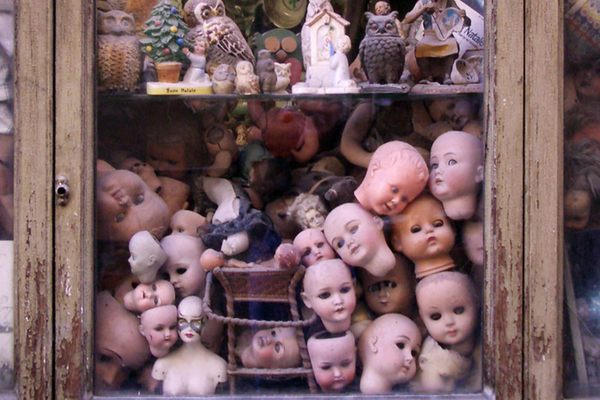

Reading the Chicago Public Library’s “Modern” list, you get the sense of just how desperate people were. The librarians took it upon themselves to fill in a full half century of potential presents, and things quickly start to get a little strange. The stretch beyond the Silver anniversary holds “Sculpture,” “Orchids,” and “New Furniture.” “Land,” at year 41, is immediately superceded in year 42 by “Improved Real Estate.” As we edge closer to 50, the librarians seem fairly impatient, falling back on bad gifts (“Groceries”) and on the tools of their own trade (“Books,” “Optical Goods—binoculars, microscopes,” “Original Poetry Tribute”). Like so many future-oriented documents, it reads less like a description of anyone’s real life and more like an impossible ideal, stuck between timeliness and timelessness and settling on “Luxuries, any kind” (year 49).

If only they had some Optical Goods. (Photo: Barn Images/Public Domain)

Accordingly, nobody really uses it.”I don’t really understand the modern list, to be honest,” says Dana Holmes, the editor in chief of Gifts.com. “Some of it could be useful to some people, but who really needs silver hollowware? It’s a very specific kind of couple who needs that, and chances are that they’re inheriting some.”

The traditional list, though, still holds some sway. “There are a handful of traditionalists and sentimental couples out there who like the ceremony and tradition of it,” says Holmes. Like the Samberg-Newsom family, younger couples tend to riff off of the theme in a way that fits their lives—a camping trip for the “wood” anniversary; “Iron Chef” cooking classes for iron. For their second, cotton anniversary, Holmes and her husband considered a cotton candy machine, but went with a hammock. “In a hammock,” she says, “you can chill out together and relax.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook