Inside a Decades-Long Quest to Measure Love

The journey of the “Love Tester,” from serious-seeming science to the penny-arcade amusements.

In the fall of 1937, Ed Keefer was a senior in the school of engineering at the University of Toledo in Ohio. Tall, slender, and bespectacled, Keefer was the president of the calculus club, the vice-president of the engineering club, and a member of the school’s exclusive all-male honor society. He also invented the Cupidoscope.

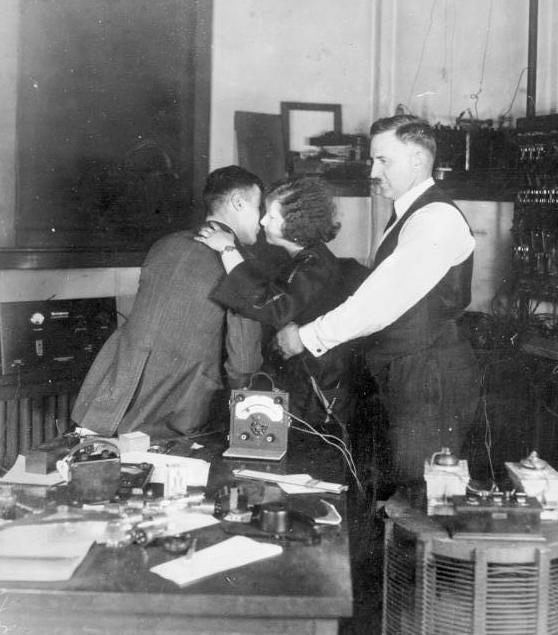

The electrical device could not have been more perfectly designed to bring campus-wide fame to its creators, Keefer and his less sociable classmate John Hawley. It promised to reveal, with scientific precision, if a couple was truly in love. As the inventors explained to a United Press reporter as news of their innovation spread, the Cupidoscope delivered on its promise “in terms called ‘amorcycles,’ the affection that the college girl has for her boyfriend.”

Built in the school’s physics laboratory, the Cupidoscope was fashioned from an old radio cabinet, a motor spark coil, and an electrical resistor. To test their bond, a man and a woman would grip electrodes on either side of the Cupidoscope and move them toward one another until the woman felt a spark—not of attraction, but of electricity. The higher her tolerance for this mild current, the more of a love signal the meter registered. A needle decorated with hearts purported to show her devotion on a scale that ranged from “No hope” to “See preacher!”

It all sounds like a slightly painful party game—but the Cupidoscope was one experiment in a serious, decades-long quest to quantify love, from the bond between two people to one’s personal appeal to possible partners. This undertaking garnered the attention of leading scientists across the United States and in Europe in the early years of the 20th century, and though some of the science behind it might still have a place in the study of emotion, it is memorialized most prominently in the penny arcade mainstay known as the Love Tester.

Folklore is filled with rituals designed to take the guesswork out of romance. The full moon, fire, the annual harvest—all have been used, and in some cases still are used, to predict the path of true love, so it follows that technological innovation would lead to new strategies for divination. In the United States and Western Europe in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the professionalization of medicine and widespread adoption of electricity held the promise of new insights into the metaphorical heart and that elusive romantic energy, to say nothing of the very real understanding of the heart’s actual electrical signals.

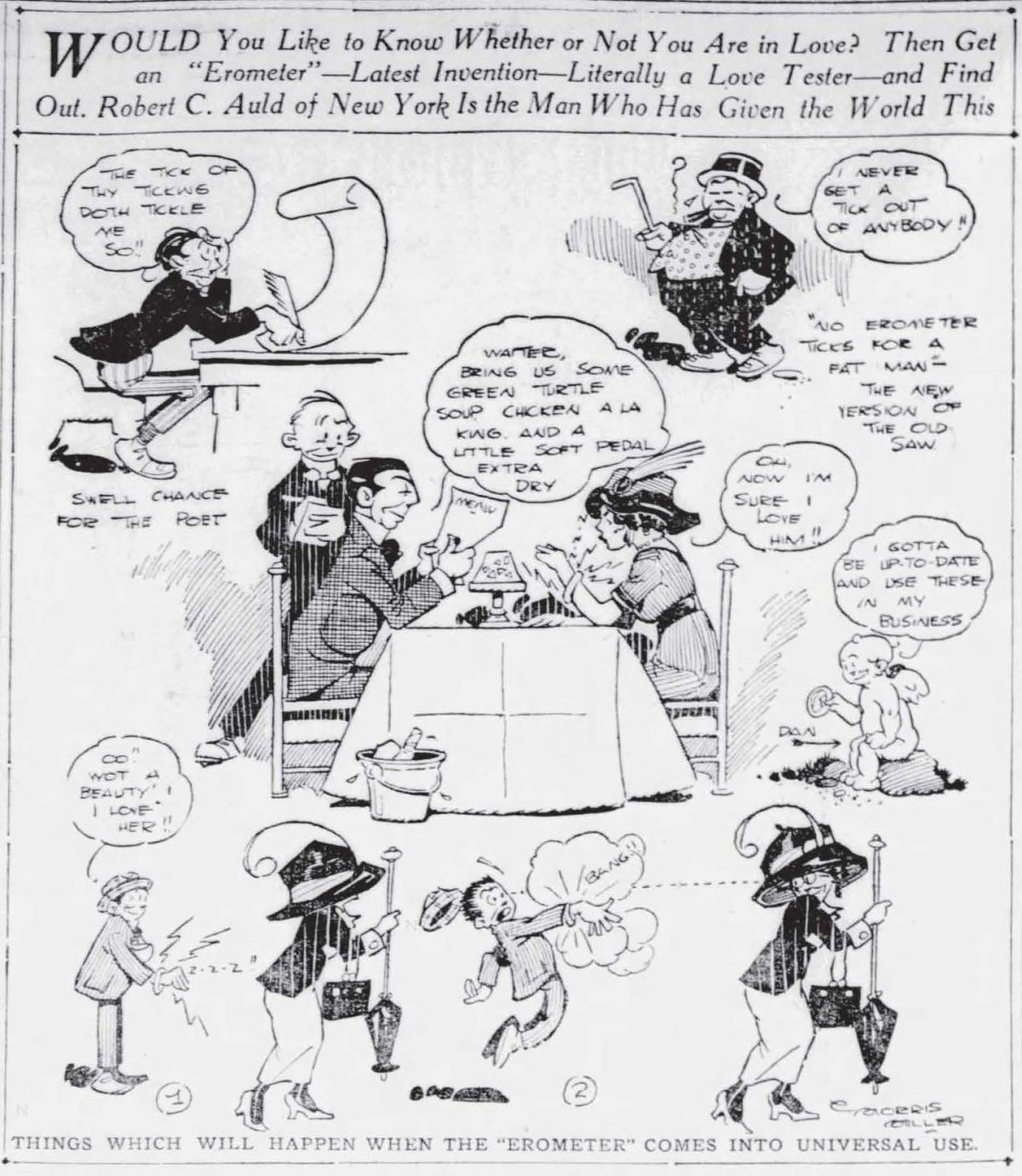

As early as 1901, a Philadelphia attorney was advocating for taking such inventions seriously: “Love-meters are in demand by every young man and woman and should be patented.” By 1910 newspapers were bemoaning that “science is slowly killing romance.” Early innovations included the plethysmograph, a doctor’s instrument still used today for measuring changes in volume in the body. In the University of Pennsylvania laboratory of esteemed psychologist Lightner Witmer, the New York World reported. the device was employed to see if the name of a certain young man or woman stirred the blood enough to register a signal.

Detecting love, ardor, or appeal was a relatively light-hearted experiment that grew out of a darker scientific pursuit of the early 20th century: detecting lies. Many of the same hypotheses that drove the development of the polygraph—that truth or deceit can (kind of) be read in the variations of one’s respiration, blood pressure, and heart rate—drove attempts to create a love meter, but the latter research was far more fun. Columbia University professor William Marston proved this when, in 1928, he hooked his version of this contraption up to a group of actresses in a Manhattan theater. He showed them love scenes starring Greta Garbo and John Gilbert, and claimed he could determine each woman’s emotional reaction. The media ate up the exhibition, and Marston’s far-less-than-scientific findings: that brunettes are more loving and passionate than blondes.

Would-be love doctors popped up everywhere. Scientists at a hospital in London claimed to have developed a “psychogalvanic” instrument that could detect affection in the electrical conductance of the skin, as did C.A. Rucknick, a University of Iowa professor whose “emotion meter” used sweat as a sign of romance. His method, which involved attaching electrodes to the palm of the hand, was superior to earlier ones that tracked respiration because “the activity of the sweat glands is absolutely involuntary,” he told the Associated Press. “Persons are learning to control their breathing.” (Skin conductance, like respiration and heart rate, remain measures used to assess emotional response today—if not love, exactly.)

The Society for Electrical Development, a group established to lobby on behalf of the electricity industry, advocated for discovering the truth of the metaphorical heart by monitoring the physical one with the “telegraphone,” a device worn on the chest to detect flutters in the presence of a lover. The same idea, newspapers from Connecticut to California reported, was endorsed by French cardiologist Rene Lutembacher, who was better known for his studies of abnormalities of the actual cardiac muscle. And at Westinghouse Electric Co., a research engineer proposed that love was a form of radiation, According to the Associated Press, he promised that “in the near future we may be able to capture and interpret these personality and thoughts through electrical impulses.”

Into this fray stepped J. Frank Meyer. He was not a scientist, but an entrepreneur who had made his name first as a printer, producing the (sometimes risqué) novelty cards in demand at the penny arcades that were newly popular in the 1910s. By 1920, Meyer had established the Exhibit Supply Company in Chicago to build the machines that sold the cards for a penny a piece, and then, when the arcades began to lose their audience to movie theaters, Meyer got more inventive, dreaming up a host of new “amusement machines” that combined modern mechanical and electrical know-how with eternal human insecurities: Are you strong enough? Are you fast enough? Could anyone love you?

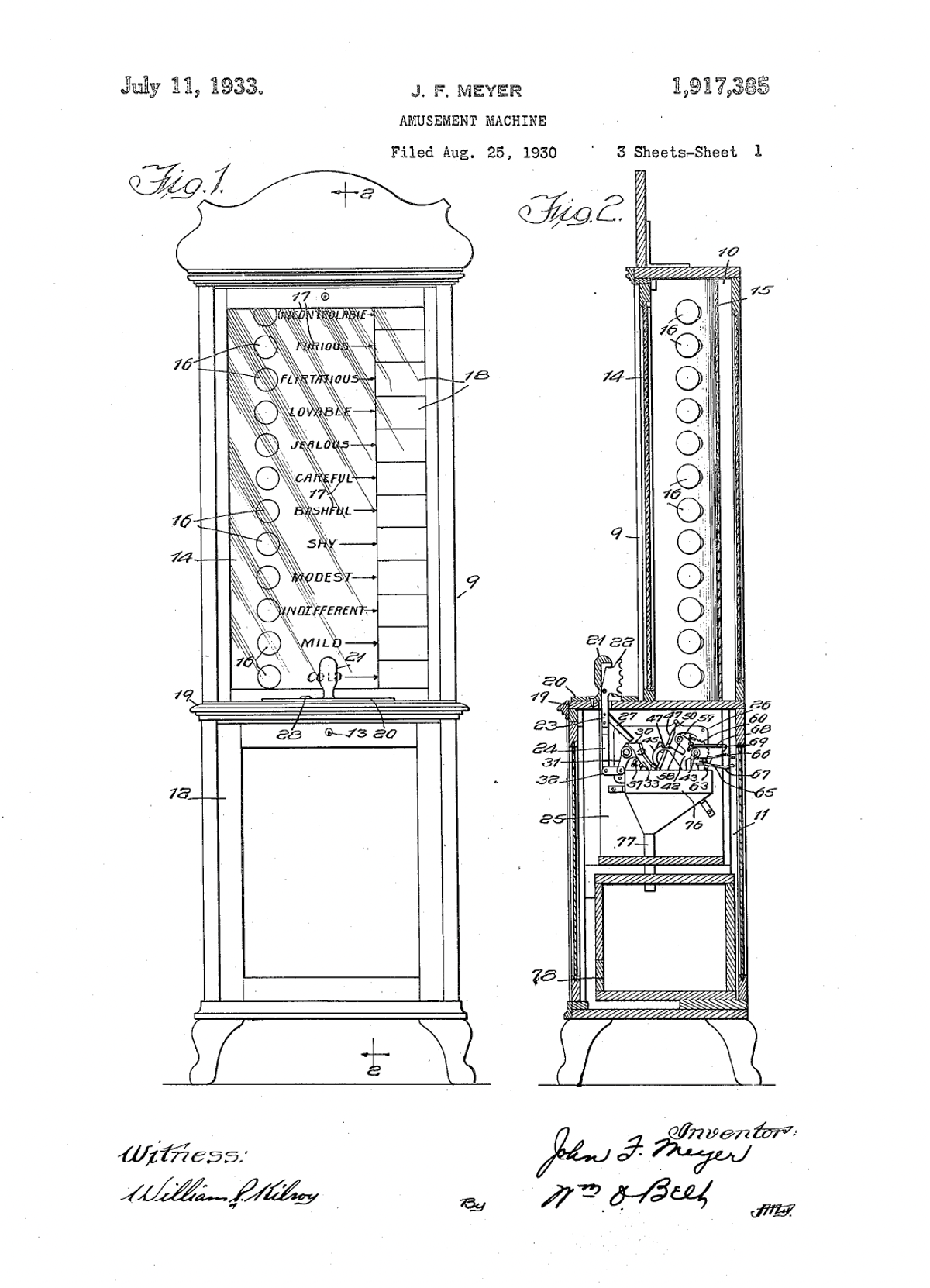

In a patent application submitted in August 1930, Meyer sketched the first penny arcade love meter—less a measure of attraction between two people than a single person’s appeal. It was a tall, narrow wooden cabinet with elegant Queen Anne feet that made it look like a hutch in a formal dining room. Users would insert a penny and then grip a gleaming metal handle molded to the shape of the fingers. The machine would then measure the user’s level of passion, from “cold” to “uncontrollable.” Several months later Meyer would name it the “Love Tester,” and submit a design patent application for a metal panel that read “Measure your sex appeal on this love meter.”

Versions of the Love Tester appeared to have been manufactured even before the patent was granted in 1933, but into the late 1930s, the appearance of the love meter at a local arcade was still enough of a novelty to warrant a newspaper mention. As scientists continued to pursue the ultimate proof of love in the laboratory, anyone with a penny could experiment at the arcade. The science underlying Meyer’s creation was as substantial as that of any of the love meters that had come before it—which is to say, there was none. When the user gripped the handle of the Love Tester, it did not detect the pulse or measure the conductance. The action set a wheel spinning inside the machine. When friction slowed it to a stop, the completed electrical circuit would light up a bulb on the meter at random. Love, it was saying, was just roulette.

It’s impossible to know if Ed Keefer and John Hawley had originally intended their love meter, the Cupidoscope, to earn them professional fame or simply invitations to the semester’s sorority bashes. (The invitations were forthcoming.) But after University of Toledo psychologist W.E. McClure dismissed the invention as, in the words of the Associated Press, “too crude” to register evidence of love, Keefer was determined to show the Cupidoscope was fit for more than a penny arcade. McClure went on to say that the device might “pave the way for scientific research to test the resistance of the individual to electrical shock under emotional strain or it may be improved to measure the determination of a subject to make a good impression before a group,” but that does not seem to have lessened the blow of the criticism.

In the first days of 1938, Keefer was presented with a national platform to prove the value of his invention when he was invited to introduce the Cupidoscope to the country on the popular CBS radio show We the People. The machine was to be tested live from Radio City by a newly married couple. But the producers already knew the outcome. They had no more need for scientific accuracy than arcade goers who pumped tens of thousands of pennies into the Love Tester, so they handed Keefer a script and didn’t bother to plug in the Cupidometer.

The Cupidometer—like all efforts before and all those after—was destined to be nothing more than a gimmick, a niche the Love Meter had proved could be quite lucrative. After his trip to New York, the University of Toledo student newspaper reported, Keefer discarded the failed science experiment, but it was soon resurrected by two enterprising sophomores who cared less about how much a woman loved her man than how much she might come to love a brand, say, a particular type of sliced bread. They tried to sell the Cupidometer as a marketing tool: Before trying the sponsor’s product, a couple’s love was lackluster, afterward, the Cupidometer registered bliss.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook