How to Make Olive Oil Like the Ancient Egyptians

Press your olives following archaeological clues provided on wall paintings and reliefs.

This story was originally published on The Conversation and appears here under a Creative Commons license.

Olive oil was one of the major commodities in the ancient Mediterranean. Alongside wine, grain and perhaps also cheese in some regions, it enveloped and permeated Canaanite, Phoenician, Greek, and Roman cultures, and was present in Egypt long before.

According to the Roman writer Pliny the Elder (1st century CE):

there are two liquids that are especially agreeable to the human body, wine inside and oil outside […] [the latter] being an absolute necessity.

Olive oil was used for a broad variety of purposes in antiquity: fuel for cooking, lighting and heating; personal hygiene; craft; and within the daily diet.

Large proportions of Greek, Roman, and presumably Phoenician agricultural texts are devoted to the production of oil.

Authors like Columella, Palladius, Pliny and Cato the Elder, and the now-lost treatise of Mago the Carthaginian—the father of agriculture—debate what tools and equipment are needed, how and where to grow olive trees, what workers are required, and the array of olives and oils.

The detail within these texts is staggering. It extends to precise instructions for creating olive oil as well recipes for various types. Combined with surviving iconography and art that depicts these processes, as well as the archaeological remains of oileries and olive groves, we can attempt to reconstruct these ancient commodities.

This process is termed experimental archaeology. Experimental archaeology is often used to fill gaps in our knowledge and help us understand the practicalities of these production techniques—particularly for objects and processes that are rarely preserved.

This is particularly true for some types of oil presses, which were made almost entirely of organic materials and survive only in exceptional circumstances.

Recreating ancient Egyptian olive oil

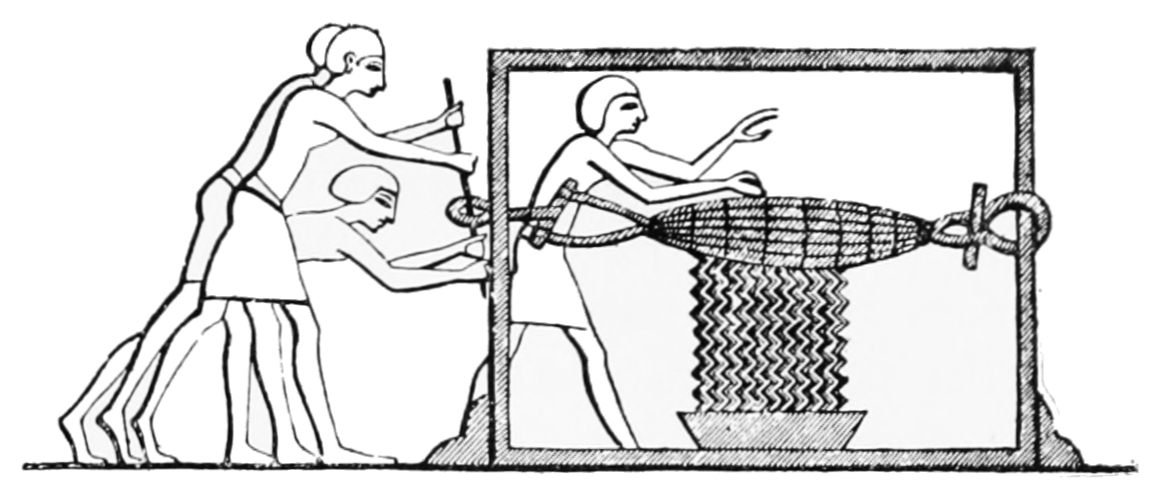

One of the earliest, if not the first, methods of pressing substances to produce a liquid such as wine or oil was by torsion.

This method involves filling a permeable bag with the crushed fruit, inserting sticks at either end of the bag before twisting them in opposite directions. This compresses the bag, and liquid filters out.

The torsion method is depicted on various Egyptian wall paintings, from the Old, Middle, and New Kingdoms. The earliest known example is in the tomb of Nebemakhet from around 2600–2500 BCE.

This method lasted millennia. There is evidence for the use of the torsion bag method from pre-industrial Venice, Spain, and Corsica, and it is illustrated in early 20th-century Italy.

Egyptian depictions of the torsion press have often been assumed to be related to wine production, but we wanted to know: Could it also be effectively used to make olive oil?

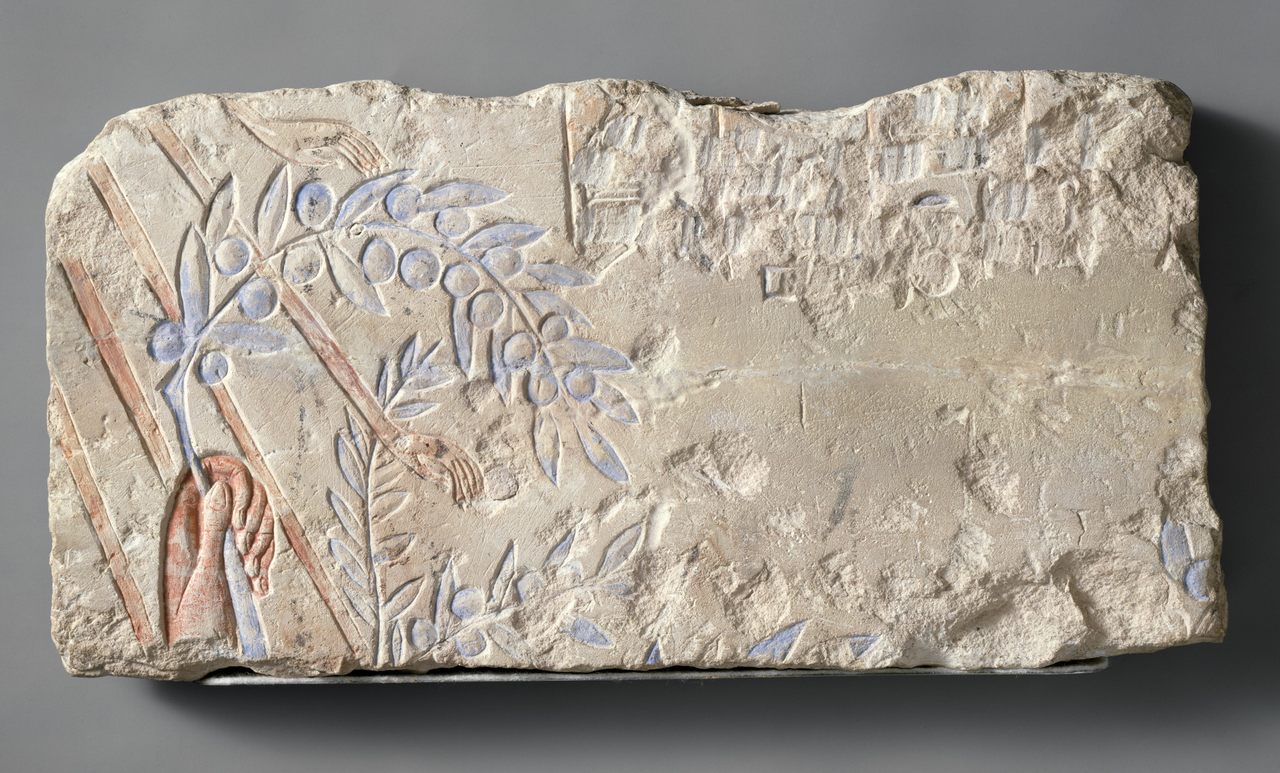

With a lack of written and structural archaeological evidence—unlike the later Greco-Roman eras—depictions on wall paintings and in relief are some of our only clues in Egypt.

Accompanied by basic olive crushing methods, known since the Neolithic era and still used until recently, we aimed to use these processes to test how effective they were and what quality of oil was achievable.

It is difficult to determine exactly what cloth was used in antiquity for the bag, so we decided to use a simple cheesecloth.

Made olive oil using a variety of #ancient methods - which worked best?! 🫒

— Dr Emlyn Dodd (@emlynkd) May 25, 2021

Experimental #archaeology gone wild! pic.twitter.com/ffP5y10nYw

A mix of green and black olives, still used by traditional Italian producers today to create high quality extra-virgin oil, were harvested in the late Australian autumn season of mid-May.

Following ancient recommendations, they were washed before processing.

Before the torsion occurs, crushing is necessary to tear the flesh of the olive. This allows for the release of oils under pressure. We used a basic mortar and pestle—a technique documented archaeologically since around 5000 BCE.

This was hard work, particularly on the less ripe green olives.

It is not surprising that advances through the Classical and Hellenistic Greek eras were made, including larger rotary mortars, called trapeta (or later, the slightly different mola olearia), allowing greater quantities to be processed with ease.

After crushing, the pulp was placed in a cheesecloth sack and a variety of torsion methods were tested: twisting on both ends; anchoring one end and twisting the other; and first soaking the fruit in hot water to release oils before twisting.

It was immediately noticeable that gentle pressure worked well, providing a slow but steady drip of liquid and minimizing any solid materials being forced through the cloth. Multiple layers of cloth were required to prevent ripping, but this also made the filtration process slower and less permeable.

A slow and gentle pressing

A compromise in the middle created the best results: a gentle, slow pressing, anchoring one end and twisting the other.

Some pressing methods separated the oil far quicker, with a fine yellow layer floating on the surface of the vegetable water in just minutes. Other methods did not separate even when left overnight and we were left with a thick brown mixture of vegetable water (the Roman amurca) and oils. Even Pliny noted “the very same olives can frequently give quite different results.”

The successful jars produced a delicious olive oil. Sharp, bitey, and with hints of pepper—just like a nice fresh-pressed extra virgin oil.

Despite the fact that almost no archaeological evidence is known of actual olive oil facilities in Pharaonic Egypt, with iconography providing the only real clues, this experiment clearly showed it is possible to press olives and produce oil using this frequently depicted method.

It is also an excellent (and relatively easy) method of making your own olive oil at home!

Emlyn Dodd is the assistant director of archaeology at the British School at Rome, an honorary postdoctoral fellow at Macquarie University, and a research affiliate at the Australian Archaeological Institute at Athens.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook