Before Jell-O, Colorful Gelatin Desserts Were Haute Cuisine

Celebrity chefs served molded jelly dishes to monarchs and royalty.

Marie-Antoine Carême made his name cooking for some of the greatest figures in France at the dawn of the 19th century, including Napoleon Bonaparte. He was arguably the world’s first celebrity chef, and later served Czar Alexander of Russia and King George IV of England, evangelizing the elaborate and expensive haute cuisine he’d helped pioneer. He even invented some of France’s best-known desserts, such as croquembouche and mille-feuille.

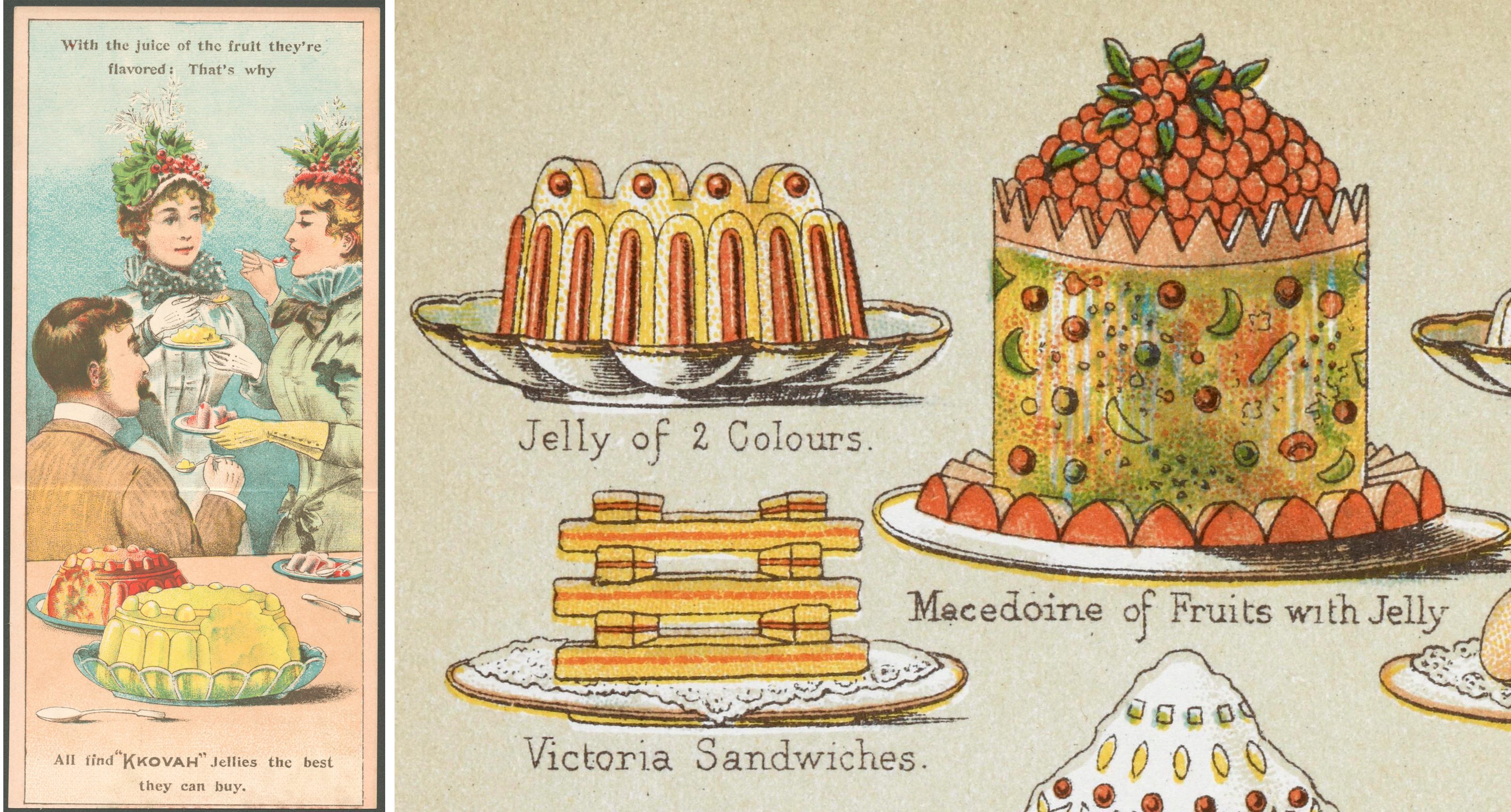

He was also a fan of gelatin. As food historian Christina Ward has noted, he was especially renowned for the massive, architecturally inspired molded gelatin dishes that often served as showstopper edible centerpieces for his feasts. In modern terms, this would be like a master chef placing towering Jell-O concoctions at a royal wedding or the French Laundry.

That may surprise American readers, since their gelatin desserts are now decidedly lowbrow. Gelatin is the cheap, boring convenience food Baby Boomers stuffed down their kids’ maws and dieters turned to in the ‘80s and ‘90s. Mid-20th century dishes such as avocado and grapefruit encased in lime Jell-O and topped with mayo are widely viewed as the nadir of American cooking—symbols of the era when everything got the gelatin treatment and the borders between salad and dessert courses blurred. Gelatin is, to many today, so childish or distasteful that a slew of articles reported, several years ago, on a free fall of sales of Jell-O and similar brands.

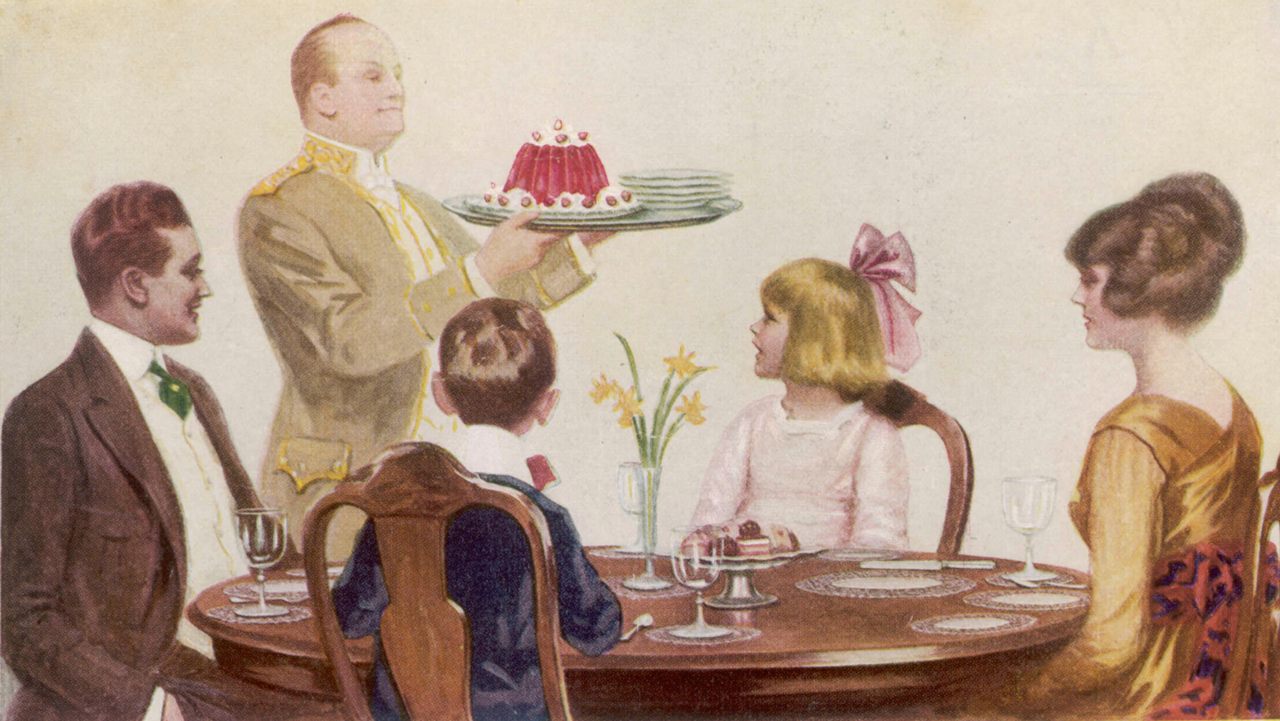

But Carême’s love for gelatin and use of it in high-end cuisine was hardly a culinary aberration. From the early Renaissance through the early-20th century, gelatin “salads” and desserts were prestigious dishes and the provenance of master chefs. “Today, people who want to parade their wealth buy a Porsche,” argues Carolyn Wyman, author of Jell-O: A Biography. “In pre-industrial days, they would instead serve their guests fancy molded ice cream or gelatin desserts.”

The contrast between modern American and historic views of gelatin is striking. So why exactly was it such a valued food for so long? And how did it fall from grace?

Gelatin proper, as opposed to starch-based “gelatin,” is basically meat or fish jelly, produced by heating and breaking down the collagen proteins found in animal tissue and bones—especially joints. This thick, cloudy jelly is quite effective at blocking air or bacteria. So as long as humans have been cooking meat and fish, we’ve likely been using gelatin to preserve it. These simple gelatins-as-preservative were seemingly, for most of history, common utility foods, and this is still the case. As Ward points out, the headcheese found in supermarket deli cases “are off bits suspended in pork jelly.”

But by the early-14th century, recipes cropped up in elite literature for increasingly complex gelatin-based dishes, such as Milanese physician Maino de Maineri’s concoction of fish boiled in wine, thickened with roasted bread soaked in vinegar and cut with cinnamon, cloves, and galingale. Ward argues that these elaborate takes on an older staple flowed naturally from the growth of wealth and international trade and travel in Europe. The urge to build a reputation as a chef or wealthy family resulted in increasingly complex and pricey dishes.

Over the coming decades, chefs seemingly realized that they could make entirely clear gelatins. This allowed them to showcase intricately layered ingredients—such as expensive fruits and spices—or color the base for vibrant edible decor. Food historian Barbara Santich once referred to medieval gelatin specialties as “the glamor dish offered at the end of a banquet, bejeweled with sparkling crimson pomegranate seeds or golden spices.”

Gelatin primarily rose to become a status symbol, though, because of the wealth implied by the time and effort required to make it regularly. Rounds of boiling and straining out impurities took more than a day to complete. The 14th-century French chef Guillaume Tirel, a.k.a. Taillevent, explained in his Le Viandier that, “He who would make a gelatin is not allowed to sleep.” Gelatin wasn’t expensive or hard to make on its own, argues medieval food historian Ken Albala. Russian families of all classes, for example, have long prepared kholodets, savory meat cuts suspended in gelatin, as a winter holiday treat. But serving gelatins, especially elaborate ones, often, rather than as a special holiday dish, was a clear sign of wealth. It showed you could hire a dedicated cooking staff to go through the arduous and (frankly) stinky process of making it.

According to historian Laura Shapiro, Americans in the mid-to-late-19th century were enamored with visually stunning foods and motivated by class aspirations. So many homemakers were eager (or socially pressured) to explore gelatin desserts, and to find easier ways to make them.

Industrialists seemingly recognized this demand. Dried and powdered gelatin cropped up in the 1840s, developed by tanners and glue makers with literal tons of animal byproduct to monetize. But tastemakers off the era seemingly took a dim view of their quality, and their inventors didn’t do much to promote them. Then, in 1890, Charles and Rose Knox of Johnstown, New York, set up the Knox Company to sell granulated “gelatine,” which cooks finally found palatable and convenient. (Their unflavored gelatin is still available today.) And in 1897, a cough syrup maker from near Rochester, New York, patented Jell-O, another granulated easy-use gelatin mix. (That brand has changed ownership several times.)

The public didn’t take to these new products right away, explains Wyman, because they were some of America’s first “convenience products” and “women didn’t understand a food that didn’t require recipes.” So both companies advertised the hell out of easy gelatin in the early 1900s.

Early Jell-O advertising campaigns leaned into the idea that the product allowed any family to easily attain what once belonged primarily to elites. Shapiro has one such ad from the 1920s hanging in her house. Its text enthuses, in part: “Land of romance. Proud and haughty Dons. Brave matadors. Lovely señoritas. The gaiety of lurid color everywhere. Spain. How the old grandees, the epicures of good food, would have enjoyed Jell-O.”

But Jell-O didn’t just zero in on this class aspiration advertising angle, explains Shapiro. At the same time, the company released ads stressing this industrialized form of gelatin was so easy to make that even a child could prepare it. Yet more ads focused on how it could be used economically as a means of food preservation. And Jell-O’s makers targeted every possible demographic, even distributing free Jell-O molds to immigrants at Ellis Island.

Gradually, the image of gelatin as cheap and easy eroded its rarified status. The Great Depression may have sped up this shift as recipe books and ads leaned into the depiction of Jell-O as an affordable way to preserve and stretch food. During World War II, too, recipes touted Jell-O as a tool for jerry rigging wartime rations into presentable meals. In the ‘50s, this association stuck as convenience food titans used it as a vehicle to showcase ration-like products. That is how we got some of our most notorious gelatin dishes. “There was a time when General Foods owned the Jell-O, Hellmann’s Mayonnaise, and Libby Canned Fruit brands,” explains Ward. The recipes they promoted to advertise their products used ingredients from each of those brands.

Gelatin dishes just got too cheap, practical, and common to be haute—at one point, a third of the average American recipe book was devoted to gelatin. (Granted, some recipes used gelatin less as a central ingredient and more as an inconspicuous thickening or volumizing agent—a use that persists today even in high-end desserts and edible decorations.) By the 1950s, Shapiro says, they no longer appeared at fancy dinner parties as a centerpiece dessert. Gelatin’s association shifted to leftovers and kids’ palates. “The innovation of the 1990s pre-packaged, ready-to-eat Jell-O cups was the final blow to gelatin’s place in culinary history,” says Ward, since the move positioned it entirely as convenient children’s food.

That doesn’t mean the prestige of gelatin vanished entirely. Elaborate gelatin salads remain popular in certain corners of America: Mormon areas in the Southwest are known jokingly as the Jell-O Belt, and cloudy tomato aspics are beloved in parts of the South. For some, they remain show-stopping visual presentations and proof of culinary prowess. As Shapiro points out, it really does take a degree of skill to perfectly layer and then unmold a towering gelatin creation. And outside the United States, gelatin dishes did not go through the same process of cultural degradation. In Mexico, for example, gelatin desserts are still widely loved, and serve as canvasses for admired edible artistry.

Gelatin could rise up the social ladder in America again. Chefs have started to experiment with unflavored gelatin as a tool in molecular gastronomy, notes Ward. And some suspect the social media era’s focus on presentation could revive interest in the visual potential of Carême-style gelatin desserts. Albala speculates that homemade gelatin could have a hipster-ish appeal, riding the pre-industrial prestige of making something laborious and elaborate. Because in the end, he argues, intricate gelatin dishes are still “pretty cool” and “stunningly beautiful.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook