The Unsung Women of the Betty Crocker Test Kitchens

For many Crockettes, the job was glamorous, fulfilling, and “almost subversive.”

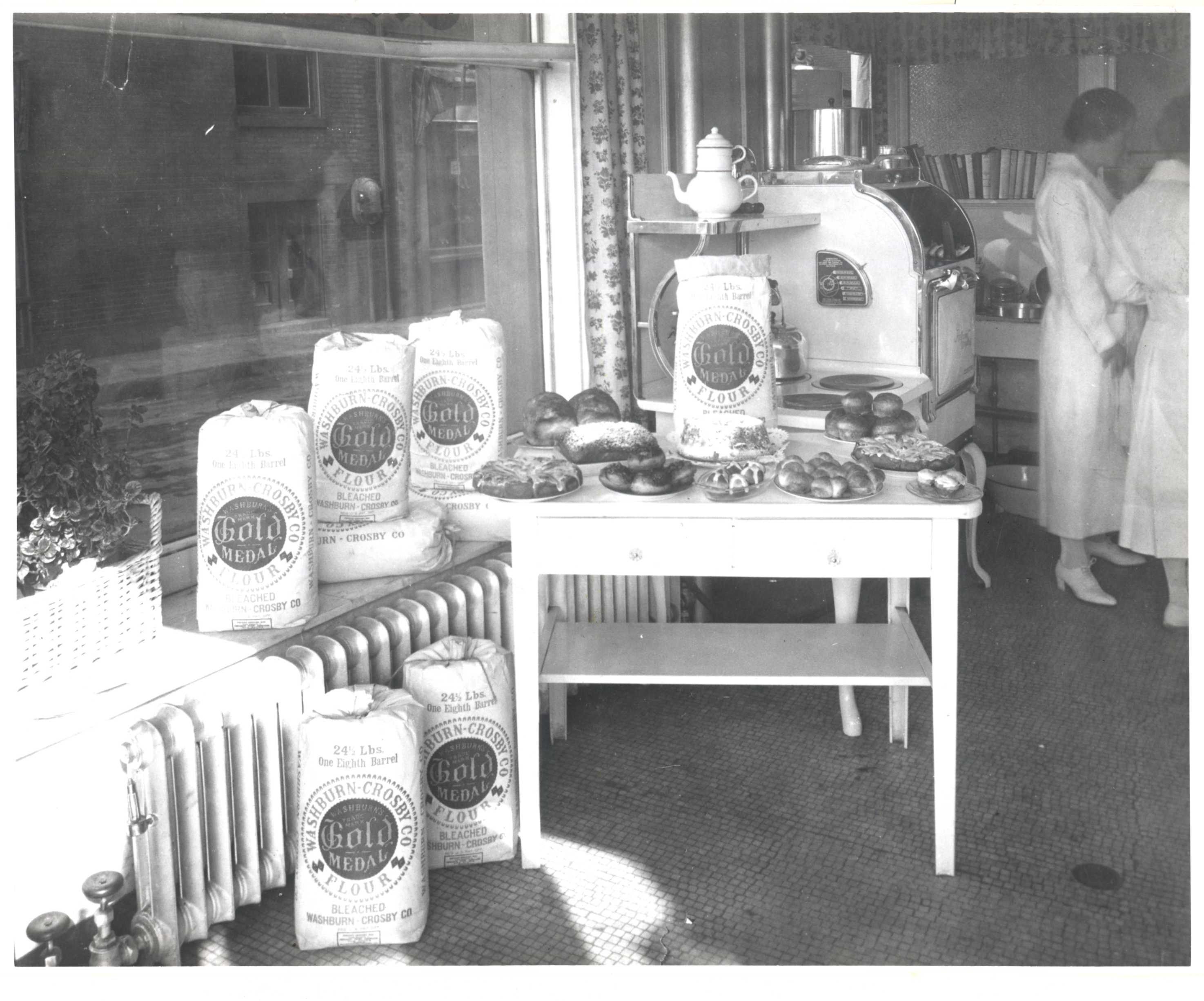

It started with a pincushion and a puzzle. In 1921, Washburn Crosby, the makers of Gold Medal flour, held a national contest. If customers completed a jigsaw puzzle and sent it in, they would be mailed a prize: a pincushion shaped like a flour sack.

The Minnesota-based company was soon deluged in completed puzzles, along with something they didn’t expect: hundreds of letters from home cooks, asking for kitchen advice. The company took on the challenge gamely, responding to all the inquiries. According to Susan Marks, the author of Finding Betty Crocker: The Secret Life of America’s First Lady of Food, “The company felt like they should have a name attached when someone would respond back to them. And they didn’t think it should be a man. They thought that it should be a woman.”

So they invented a person. For her first name, Betty. “It was really nice and sweet, and everybody knew a Betty,” says Marks. Crocker was the last name of a well-liked company executive. The advertising department sought out female employees to respond to the letters, and eventually staffed an entire department with women who knew their way around a kitchen. “It all grew rather quickly from there,” Marks says.

Ever since, the image of a brunette white woman has stared out of advertisements, food packaging, and the pages of cookbooks. She was fictional, a marketing tool used to sell Gold Medal Flour, Bisquick, and other American staples. But at a time when women were discouraged from working outside the home, the real women behind the dozens of cookbooks, hundreds of advertisements, and thousands of letters emblazoned with the name “Betty Crocker” turned an illustration and a name into a corporate powerhouse. Despite prevalent gender discrimination, many remembered their time as “Crockettes” with immense fondness.

In 2002, Barbara Jo Davis sat down with Linda Cameron, an interviewer for the Minnesota Historical Society. Davis is an accomplished businesswoman, the president and owner of a barbecue sauce company and the first president of the Coalition for Black Development in Home Economics.

As a child, though, Davis didn’t want to grow up to be a businesswoman. “Actually, when I was about 12, I decided I wanted to be Betty Crocker,” Davis told Cameron. By the time Davis first heard of Betty Crocker, the brand had decades of experience in advertising their near-scientific but homey approach to food.

In the early 1920s, Washburn Crosby sent women to teach community cooking classes. This was their way of piggybacking off the home-economics movement. Since the 1800s, the field of “domestic science” aimed to standardize and apply scientific principles to how people worked in the home, especially cooking. In the first half of the 1900s, many women studied home economics at universities, which often required credits in chemistry, biology, dietetics, and mathematics, opening up new fields to female workers.

To capitalize on this interest in modern cooking, Washburn Crosby bought a failing radio station in 1924. The Betty Crocker Cooking School of the Air brought the dulcet tones of actresses playing Betty Crocker to millions of Americans. By the time Washburn Crosby merged with other flour companies to become General Mills, she was a bona-fide phenomenon, receiving more mail than a Hollywood starlet every week. The Betty Crocker formula—genuinely helpful kitchen advice, a familiar but slightly mysterious hostess, and lots of product placement—proved to be a powerful combination.

The secret to the success of Betty Crocker, says Marks, was the talent in the kitchen. And while hundreds of women worked under the Betty Crocker name, one in particular shaped the character for decades. Marjorie Child Husted, hired at Washburn Crosby in 1924, became head of the Home Service Department in 1927. She often scripted the Betty Crocker radio show herself, and showed a keen understanding of what her listeners wanted: fellowship with both the voice on the air and with other listeners. The early 1900s were a tumultuous time, with technology developing at a rapid place and millions of people living far away from their families. Having a calm, authoritative voice direct you on how to cook a roast or pinch a pie crust must have been a relief, even if that voice also constantly encouraged you to buy Gold Medal Flour.

Radio shows and responses to personal letters weren’t enough Betty for the public. General Mills began releasing recipe pamphlets under her name. There was 1933’s Betty Crocker’s $25,000 Recipe Set Featuring Recipes From World Famous Chefs For Foods That Enchant Men and Betty Crocker’s 101 Delicious Bisquick Creations As Made And Served by Well-Known Gracious Hostesses; Famous Chefs, Distinguished Epicures and Smart Luminaries of Movieland. These booklets often featured fast dinners, innovative treats for shock and awe at the church potluck, and culinary knowledge, with most, if not all recipes containing at least one General Mills product for homemakers to buy.

To sell the maximum amount of flour, General Mills needed recipes, and lots of them. In Husted’s opinion, such recipes had to be nearly perfect in order to maintain Betty Crocker’s aura of omniscient culinary prowess. So, Marks says, “they developed what they call triple-testing, which sounds like three tests, but it’s three series of tests.” First, staff thought up a recipe, adjusting measurements and baking times over and over. Then, the recipes were sent to hired home cooks in the Minneapolis area, who tried the recipe and took copious notes. Those notes went back to company headquarters, where kitchen staff under Husted incorporated the suggestions into the final product. If a recipe successfully made it through this testing gauntlet, then it was good to go. If not, it was filed away into a massive library, perhaps to be unearthed as inspiration someday.

Working at the Home Services Department, soon to be called the Betty Crocker Kitchens, was prestigious. “You needed a degree in home economics,” says Marks. Only the best could work out of the test kitchens at the downtown headquarters. Advertisements even featured headshots of the employees, along with their degrees and accomplishments.

“These women that I interviewed, and they’ve all passed away now because it was so long ago, they said working for the Betty Crocker Kitchens was the most glamorous job you could get if you were in home economics,” says Marks.

Intrigued by the professional air that General Mills encouraged, visitors to Minneapolis often wanted to see the Crockettes at work. It was reminiscent of how visitors to Silicon Valley today haunt the outskirts of the Facebook and Apple campuses. But unlike secretive tech companies, General Mills threw open their doors and even provided a phone number for tour requests. Over the decades, foreign royalty and American presidents came to pay their respects. Awed fans came in asking if Betty was at work that day. Often, wrote Marks in her book, receptionists kept tissues on hand for the inevitable tears when visitors were told that she didn’t actually exist.

In a way, though, she did exist. Husted ushered Betty Crocker through the stock market crash of 1929, the Great Depression, and World War II. Despite the enormous dip in American incomes in the 1930s and the rationing of the 1940s, Betty Crocker helped keep General Mills flourishing. Husted approached her work with pride and upheld Betty Crocker as a resource and a friend to women working hard for their families with little support or recognition. “Women needed a champion,” she told a magazine in 1948. “They needed someone to remind them that they had value.”

For the women working in the Betty Crocker Kitchens, the role provided not only a salary but glamor and a creative work life. The number of curious visitors to the kitchens kept growing, and when General Mills moved its headquarters to the suburbs in 1958, they took special care to turn the Betty Crocker Kitchens into a destination, a fantasy of themed cooking spaces. Over the years, there was the Arizona Desert Kitchen, the Cape Cod Kitchen, the Chinatown Kitchen, and the Hawaiian Kitchen. To be fair, these were generally just for show. Some of the kitchens, though, were the sites of real, grueling work.

Ralcie Ceass, also interviewed by Cameron in 2002, started out her career as a Kitchens tour guide in 1966. Ceass, though, had a home-economics degree, and soon rose to the role of supervisor, overseeing the Kamera Kitchen. There, products and recipes were photographed and filmed for Betty Crocker cookbooks and commercials. For a single commercial, she told Cameron, her team would bake seven to eight cases of cake mix: 84 to 96 mixes, total.

“They were required to do so much,” says Marks. “So it wasn’t just cooking and baking and recipe testing and outreach with women that would come into the kitchens. They were also part of the marketing and part of the advertising.”

But despite the role Husted and other women played in building Betty Crocker into a major brand, they were often overlooked and under-appreciated by the mostly male executives.

“They had such an important role, and they were really running the show,” Marks says. “[Still] in many ways, it was considered women’s work and not all that important to the company.”

Davis certainly thought that was the case. She started at Betty Crocker in 1968 as one of the home economists, then within a few years became a supervisor, then a manager. “We were expected to, you know, make birthday cakes for the management and all of that kind of thing,” she recalled. “We were just thought of as the girls in the kitchens and no one respected us as professionals who had degrees and who knew what we were doing.”

She particularly recalled one incident. According to her, General Mills executives wanted to piggyback off the successful 1970’s partnership between Bundt and Pillsbury, and pushed through the Ring Cake Supreme mix without the usual careful testing. If you followed the directions to the letter, the cake came out perfect, “but the majority of consumers out there could not duplicate it. People were mailing us their cakes; they were that bad,” Davis said, calling the product release “a disaster.”

It was something of a comeuppance for those who didn’t trust Crockette input, Davis believed. “It had the R&D people scrambling. We, in the kitchens, said, ‘This cake should not be on the market,’ but, you know, we were just ‘the girls in the kitchen.’”

Nevertheless, Davis excelled in the Betty Crocker Kitchens. One of her achievements was helping to develop Hamburger Helper, the one-pot stovetop casserole introduced to the Betty Crocker line-up in 1971. After working there for decades, she considered herself a historian and mentor to younger staff. “I think what I loved most about that part of the job as a supervisor and, then, as a manager was the personnel development side, watching these young home economists develop and learning their jobs,” she said.

By the 1980s, the star of the Betty Crocker Kitchens and Betty Crocker herself had faded somewhat. Most women no longer yearned to be homemakers (if they ever truly did) and more opportunities than ever were available outside the home. The Kitchens closed to public tours in 1985, leaving a wave of sadness in its wake. “Reports from the few people I know who visited the seven kitchens leave me yearning,” says a regretful cook in Marks’s book. “They speak of the Hawaiian room, the Southwestern room, of multiple microwave ovens and of clever magnetic strips for holding recipes at eye level. They recall glamorous women measuring everything with precision, cooking colorful, imaginative meals from scratch.”

Marks takes a more equivocal stance towards the Betty Crocker mystique. “The women who worked there were almost subversive in the way that they elevated this character and with it, this idea of ‘You can do it, and Betty can help you,’” she says, quoting the slogan used by Betty Crocker for decades. “You can argue, too, that it kept women down, because it was in such a stereotypical role. There’s merit to that.”

Yet home economist Ruby Peterson, who worked at the Kitchens in the 1950s, and who Marks remembers with fondness, would likely disagree. “She said that every person you talk to will say the same thing, that the best experience in the world was working at Betty Crocker Kitchens,” Marks recalls.

“Although, did they get paid enough?” Marks adds with a laugh. “Probably not.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook