A Rare Recipe From a Talented Chef Enslaved by a Founding Father

Despite James Hemings’s leading role in Jefferson’s kitchen, he’s credited with only a handful of recipes.

To believe the legends, Thomas Jefferson was as much a chef as a statesman, the architect of the modern American diet and the person behind such modern European-American classics as vanilla ice cream, steak and fries, and mac and cheese.

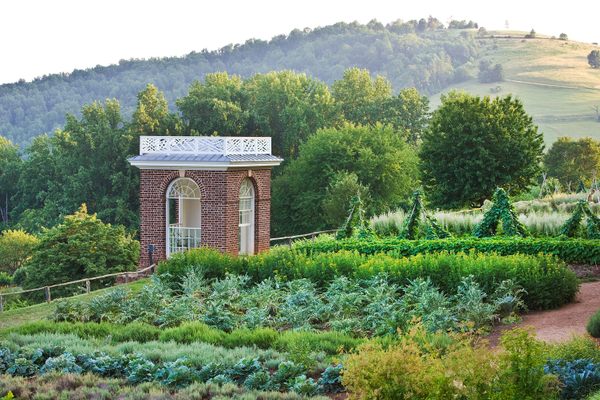

The truth is that Jefferson’s connection to the kitchen was decidedly hands-off. At Monticello, his vast Virginia plantation, the third president entered the room only to fix the clock. And while Jefferson did take an active interest in culinary matters, including importing vanilla with the specific intention of using it in ice cream, there’s little evidence that he was the first person to bring any of these recipes to the United States. Jefferson is certainly responsible for copious writings on food and cooking, including about 10 recipes that exist in his own handwriting, but it’s extremely unlikely that any of these were developed or even cooked by the man himself.

Instead, Jefferson’s famously wonderful dinners were the work of legions of talented enslaved chefs and kitchen hands. Among them was James Hemings, his enslaved chef de cuisine and the brother of Sally Hemings, who was also enslaved by Jefferson and is believed to have borne him multiple children.

Born into slavery in 1765, Hemings became Jefferson’s property at the age of nine. The two were actually related by marriage: Hemings was the son of Jefferson’s father-in-law. (Though Jefferson surely knew as much, this does not ever seem to have been acknowledged.) Early on, his many talents and lighter skin seem to have created more options for him than for the average enslaved person at Monticello, leading him to rise up through the ranks. After becoming Jefferson’s messenger and coach driver at 14, he received a life-changing opportunity at the age of 19: to accompany the statesman to Paris, where he would be trained as a chef, at Jefferson’s “great expense,” and learn to speak French.

It’s hard to overstate how unusual Hemings was, in terms of both his gifts and his influence, says Michael Twitty, a food historian and the author of The Cooking Gene: A Journey Through African American Culinary History in the Old South. Even Hemings’s literacy made him an anomaly. “Here’s the bottom line: If you are an enslaved person living at that time, knowing what state you’re in, what county you’re in, what the nearest river is, where the nearest town is, what your name is, what your name looks like written on paper or printed, how to spell the word N-E-G-R-O-E-S or S-L-A-V-E, or what time it is—that’s extraordinary.”

Hemings could do all these things, and more. He was a fastidious note-taker, with a strong sense of what Twitty describes as “proprietary knowledge” over his own recipes. Even in France, he distinguished himself with his knowledge of French cuisine, helping Jefferson develop a local reputation as a good host who “lives well and keeps a good Table and excellent wines,” as one guest put it.

By the time he was 21, Hemings was running the kitchen at the Hôtel de Langeac, Jefferson’s official residence on the Champs-Élysées. His menus suggest confidence and imagination, running the gamut from capon stuffed with Virginia ham and chestnut purée that was served with calvados sauce to boeuf à la mode.

Hemings and Jefferson spent five years in France, during which Hemings hired a tutor, was paid wages, and took on many of the ways of life previously forbidden to him as an enslaved person in the United States. It’s not clear why he did not seize the opportunity for his freedom through the French courts, following in the footsteps of many enslaved people from French colonies who sought emancipation.

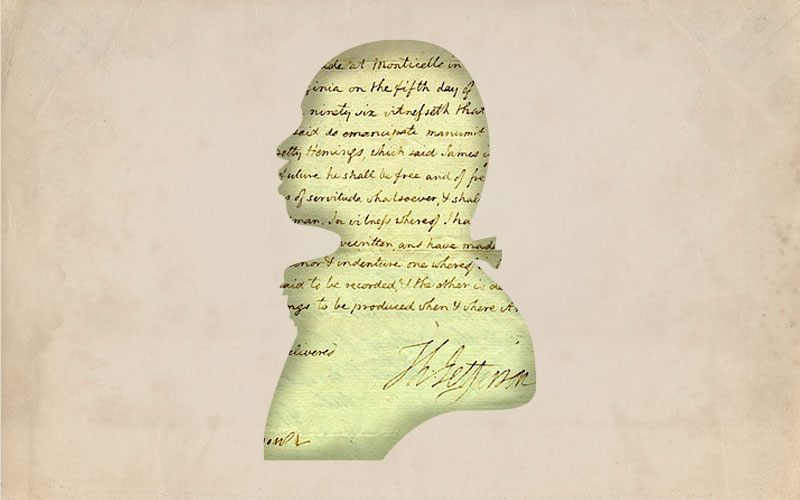

Instead, when the two returned to America, Hemings continued to work for Jefferson in abolitionist Philadelphia, where, once again, he could become a free man. Though he didn’t act on it then, in 1793, he managed to negotiate his escape: He would return to Monticello for a time, if he were promised his freedom. Jefferson agreed, committing begrudgingly to release Hemings on the condition that he train his successor, his brother Peter: “This previous condition being performed, he shall be thereupon made free.”

Despite Hemings’s considerable influence and skills, it’s difficult to pinpoint exactly which recipes were his own and which he may have helped to develop. A macaroni and cheese recipe is one likely candidate, as are a selection of different “dessert creams.” Jefferson’s granddaughter, Virginia Jefferson Randolph Trist, helped to collect and collate some 300 recipes served at Monticello, many of which tell the story of its enslaved cooks, including a recipe for gumbo.

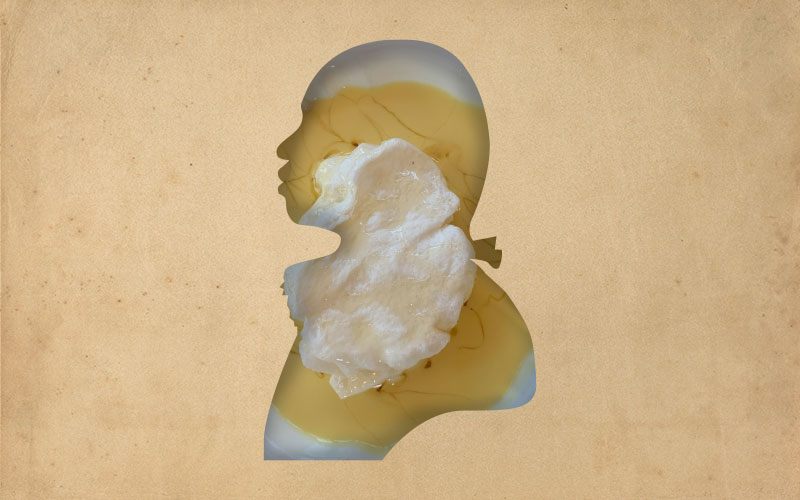

But there is one recipe that we know more or less for sure came from Hemings. Also recorded by Trist, and attributed to “James, cook at Monticello,” “snow eggs” are clouds of soft, poached meringue, set in a sea of crème anglaise. (In French, the same dish is known as oeufs à la neige, or îles flottantes, meaning “floating islands.”)

Others recipes have somewhat murkier origins. Jefferson’s famous handwritten recipe for vanilla ice cream, for instance, is often attributed to Adrien Petit, his French butler. While Petit wasn’t as connected to the kitchen as Hemings, Jefferson expected his butler to be familiar with all things culinary, and Petit would have been expected to oversee both what was purchased at the market, and the dessert course. (Jefferson’s granddaughter also recorded a virtually identical ice-cream recipe, which she attributed to “Petit.”)

When it comes to the ice-cream recipe, there’s complicating evidence that points to Hemings. The pieces of the puzzle are all there—the experience in French kitchens; the fact that it works perfectly (and is delicious, if a little rich); even Jefferson’s decision to write it down. Twitty believes Hemings may have dictated it to Jefferson on his departure for safekeeping. This in itself was atypical: “Most enslavers did not have to say, ‘‘You know what, I need to get a recipe from you,’” says Twitty, “because they already knew that person was there for life.”

The custard used in the ice-cream recipe also bears a resemblance to the crème anglaise used for Hemings’s snow eggs, though the two are not identical. That said, there’s a limit to how much room for variety there can be in a simple egg custard.

After Hemings’s manumission, in 1796, he jumped from job to job, competing unsuccessfully with less able white peers, usually with far less training. Letters from Jefferson seem to suggest that Hemings was struggling: In a 1797 letter to his daughter, Mary, he writes, a little anxiously, “James is returned to this place, and is not given up to drink as I had before been informed. He tells me his next trip will be to Spain. I am afraid his journeys will end in the moon.” Hemings does not seem to have made it to Spain—especially as Monticello and the family he had left behind kept calling him back, often for stints of paid work. “He came back, and left, and came back, and left, and came back—and then didn’t come back,” says Twitty.

Though we know the basic shape of Hemings’s life, and particularly his life with Jefferson, there’s far more we don’t know. He never married nor had children; there’s some suggestion he may have had a somewhat fluid sexuality, says Twitty. A year before Hemings’s death, as he drifted from position to position, Jefferson was elected president and sought out Hemings to run his White House kitchen. The two seem to have sparred over the position: Hemings wanted a formal offer befitting his training; Jefferson did not feel compelled to make it. The role eventually went to someone else. In 1801, aged 36, Hemings died by suicide.

Despite a sad and untimely end to Hemings’s own life, his talents, experience, and training continue to resonate. He played an essential role in popularizing French cuisine in the United States, and directly inspired generations of Monticello chefs, who benefited from his expertise and recipes. “The chefs at Monticello spread that knowledge around,” says Twitty. “Wherever the liberated or soon-to-be-liberated people from Monticello went, they became caterers of renown.”

To remember and celebrate this unsung culinary genius, try his recipe for “snow eggs.”

James Hemings’s Snow Eggs

Adapted from the Papers of Trist and Burke Family Members

Serves four

5 eggs

6 ounces sugar

1 tablespoon powdered sugar

2 cups whole milk

½ teaspoon rose water or orange blossom water

Small pinch of salt

Honey to serve

1. Make the crème anglaise

Separate your eggs into two containers and put the egg whites aside. Over a medium heat, heat the milk, sugar, and about ¼ teaspoon of either rose water or orange blossom water in a small saucepan, stirring occasionally. When the milk is simmering but not boiling, add the egg yolks, whisking continuously. Continue whisking over a medium heat until the mixture has begun to thicken and coats the back of a wooden spoon.

Place a mixing bowl full of ice in the sink; place a smaller bowl inside it to chill. Once the mixture has thickened—but while it is still runny enough to pour—run through a fine mesh sieve into the smaller bowl and leave to chill, stirring occasionally. Place in the fridge to chill further.

2. Make the meringue

Beat the egg whites, powdered sugar, a small pinch of salt, and another ¼ teaspoon of rose water or orange blossom water until the whites are stiff and shiny, or “until you can turn the vessel bottom upward without their leaving it,” in Hemings’s words.

3. Poach the meringue

Place a wide, shallow pan of water on a medium-high heat. As it comes to a simmer, line a large plate or baking tray with paper towels. Using a large tablespoon, scoop a generous dollop of the egg white mixture into the simmering pan of water, where it will float. You should be able to fit two or three in there, depending on the size of your pan. After two minutes of poaching, very carefully flip over the meringues, poach for another two minutes, then lift out and drain on the paper towels.

Serve each person two or three meringues along with a generous serving of the cold crème anglaise. Drizzle with honey to taste (the dessert is already very sweet).

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook