White Rice Is Bland? These Japanese Researchers Beg to Differ

Japan’s food world is eagerly awaiting an upcoming “flavor dictionary.”

If you ever find yourself in Japan, try this little experiment. Ask a local to explain the special appeal of takitate gohan—freshly cooked white rice. Not about how filling it is, or its versatility as a complement to savory or sour dishes. Ask about the taste, the texture, and the aroma.

There’s a lot that you can say in Japanese about rice: how the grain looks, smells, and tastes, and how it physically feels from first bite to final gulp. You’ll hear words like plump (fukkura), faintly sweet (amai), piping-hot (hoka-hoka) kernels with a shiny (tsuyayaka) paleness (shiroi); individual grains (tsubukan) with a springiness (nebari); the steam filling the room with the scent of home. By the end, you’ll grasp a basic truth about plain rice in Japan: It’s never bland.

But how many descriptors for white rice exist there, actually? One person has counted how many expressions there are. “Around 7,000,” said Fumiyo Hayakawa, a senior researcher at NARO, Japan’s National Agriculture and Food Research Organization. But is the flavor really that complex and varied? It depends on what rice means to you, Hayakawa said. “Rice isn’t just any starch for me. It’s the foundation of our culinary culture. It’s our shushoku, the staple food of Japan.”

For the past three years, Hayakawa and her colleagues Takayuki Umemoto and Yuko Nakano have worked with Itochu Food Sales and Marketing Co. to track down Japanese words and phrases describing the taste, texture, aroma, and appearance of rice. They surveyed sensory analysts, combed through food articles and research journals, and even read rice cooker catalogs. But they’re not done yet.

Hayakawa and Itochu are now whittling down their list. When they finish sometime between now and March 2025, they will have accomplished a first: a comprehensive Japanese-language rice lexicon. Think of it as a flavor dictionary for Japan’s ¥5 trillion ($33 billion) rice market. It will feature more than 100 essential terms for the features of rice, each clearly defined, with synonyms, antonyms, and supplemental notes. It will also include words describing cooled rice and ready-to-eat precooked rice. Hayakawa declined to share her current list. But she notes that “the lexicon will be freely available for anyone to use.”

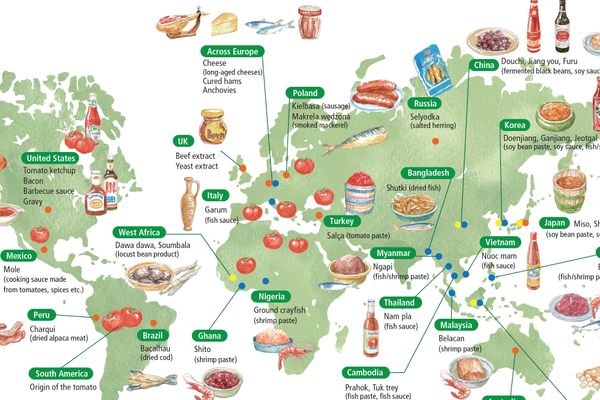

Lexicons standardize the jargon for a particular food or drink. In Japanese, there are lexicons for sake, miso, cheese, coffee, whisky and soy sauce. They’re mainly used for tastings by sensory analysts and trained panelists, whose assessments help R&D labs, product developers, and marketers tweak formulas and target specific audiences. But when lexicons find their way into tasting notes, flavor maps and training courses, they can influence the way an entire industry speaks. Itochu Food Sales and Marketing is a major supplier of rice for restaurants and convenience store bento box meals, sushi, and rice balls, with annual sales of nearly ¥200 billion ($1.3 billion). The importance of rice to Itochu is why company officials asked Hayakawa to take on this project in 2021.

For years, Itochu has struggled with vague rice terminology. When trying to match customers with specific rice varietals, Mikiko Ando, who works at the company in rice quality control, regularly hosts tastings. “It takes a long time,” she said. “Even when we are using the same words, we could be talking about different things because many of the words haven’t been strictly defined. And because of that we might not be giving them exactly the rice they’re asking for.”

Ando’s colleague, Koji Yoshizawa, once fielded a complaint years ago from a sushi chef, who said that Itochu’s rice wasn’t going down smoothly (nodogoshi ga warui). Yoshizawa didn’t understand. Was the chef referring to a gritty feeling in the throat from the kernels? When pressed for details, the chef only repeated his complaint. “We had no way of clearing it up,” said Yoshizawa, a manager on the corporate planning division’s rice quality management team.

The confusion over lingo is not limited to Itochu. “Consumers think rice that’s juicy (mizumizushii) is delicious, but to a farmer that’s a complaint that he didn’t properly dry the kernels after harvesting,” said Shinichi Katayama, fifth-generation owner of Sumidaya Shoten, a neighborhood rice shop in Tokyo.

The problems are compounded by another facet of Japan’s rice market: There are far too many options. Hundreds of rice varietals exist, with brand names like Koshihikari, Tsuyahime (Shiny Princess) and Hitomebore (Love at First Sight). Each one has been bred for specific traits: extra sweetness or large kernels or a firm texture that’s best with curry or in a gyu-don beef bowl. The idea that these small differences matter—like single-origin coffees or grape varietals in wines—have been popularized in mainstream magazines and on TV shows by “rice meisters” and “rice sommeliers” who use flavor maps to offer recommendations. It’s all a bit much for most consumers, and even some chefs.

There’s a lot of excitement in the Japanese food world about the upcoming lexicon, mostly because of Hayakawa’s involvement. Among sensory-science wordsmiths in Japan, she is a standout. Over the last three decades, Hayakawa has created Japanese-language lexicons for coffee, tomatoes, jam, baguettes and pasta. She has made TV appearances and has written a weekly column for a national daily newspaper.

However, Hayakawa is best known for her work on a Japanese food texture lexicon. In a 2012 paper in The Journal of Texture Studies, she listed 445 Japanese words describing how food feels in the mouth, and most were onomatopoeia. (By comparison, English has just over 130 food-texture words, while French has around 220 and Chinese 140.) Japanese has around 2,000 onomatopoeia. They’re so much a part of talking about food in Japan that you can use some of them as search terms on recipe websites.

But there’s much more buzz over Hayakawa’s recent work about rice. Japanese newspapers, magazines and TV broadcasters have been eager for updates about the lexicon. Rarely has Hayakawa faced so many media requests. Probably because it’s about the country’s most important staple food. Plus rice is in the news because consumption of the grain in Japan has fallen to its lowest levels since the 1960s.

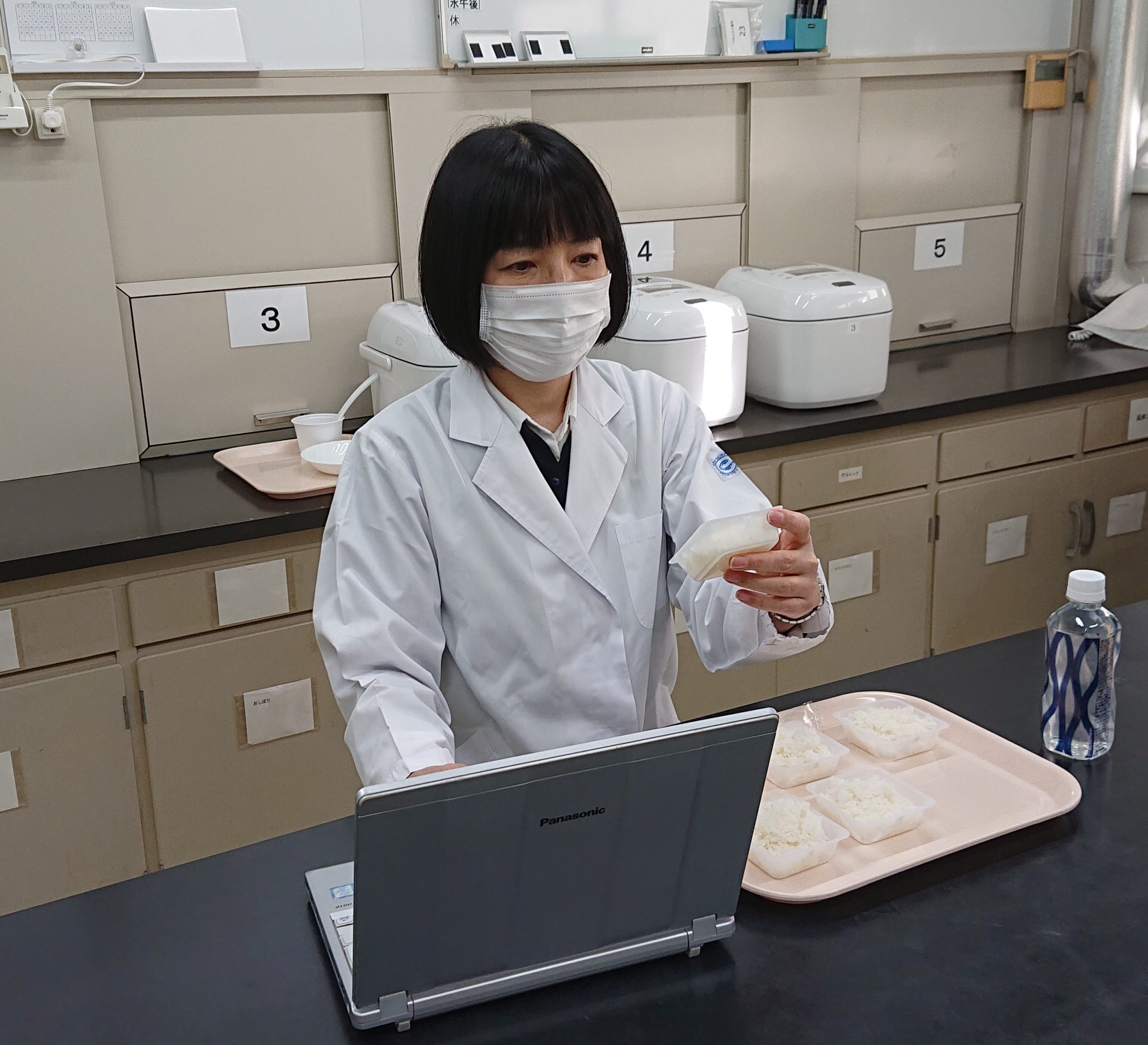

On a recent afternoon, Hayakawa presided over a meeting at NARO, which is located in Tsukuba, two hours northeast of Tokyo. She and five others—two from her laboratory, plus Itochu’s Ando and Yoshizawa and one other colleague—were seated around a conference table. They debated how to distinguish the idea of fresh (sawayaka) from floral (hana no yo na) and raw (nama). They connected the word roasted (baisen) to almonds and toasted soybean flour.

When Hayakawa asked what everyone thought of the word moist (shittori), someone compared it to Japan’s egg-based castella cake. Another person thought it sounded less unpleasant than becha-becha, which is a wet-sticky-viscous texture from cooking with too much water. Someone else asked: Is it the opposite of pasa-pasa (dried out and stale)?

“When we talk about juicy (mizumizushii), it’s supple and firm,” said Hayakawa, who sat at her laptop editing a spreadsheet. “Moist isn’t like that. It’s more appropriate for cooked rice that has been left out for an hour.” This continued for a while before she finally changed the subject. Two hours later, when the meeting ended, Hayakawa exhaled loudly. “I didn’t think that would be so hard,” she said.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook