In Mammoth Lakes, Bears, Tourists, and Locals Learn to Coexist

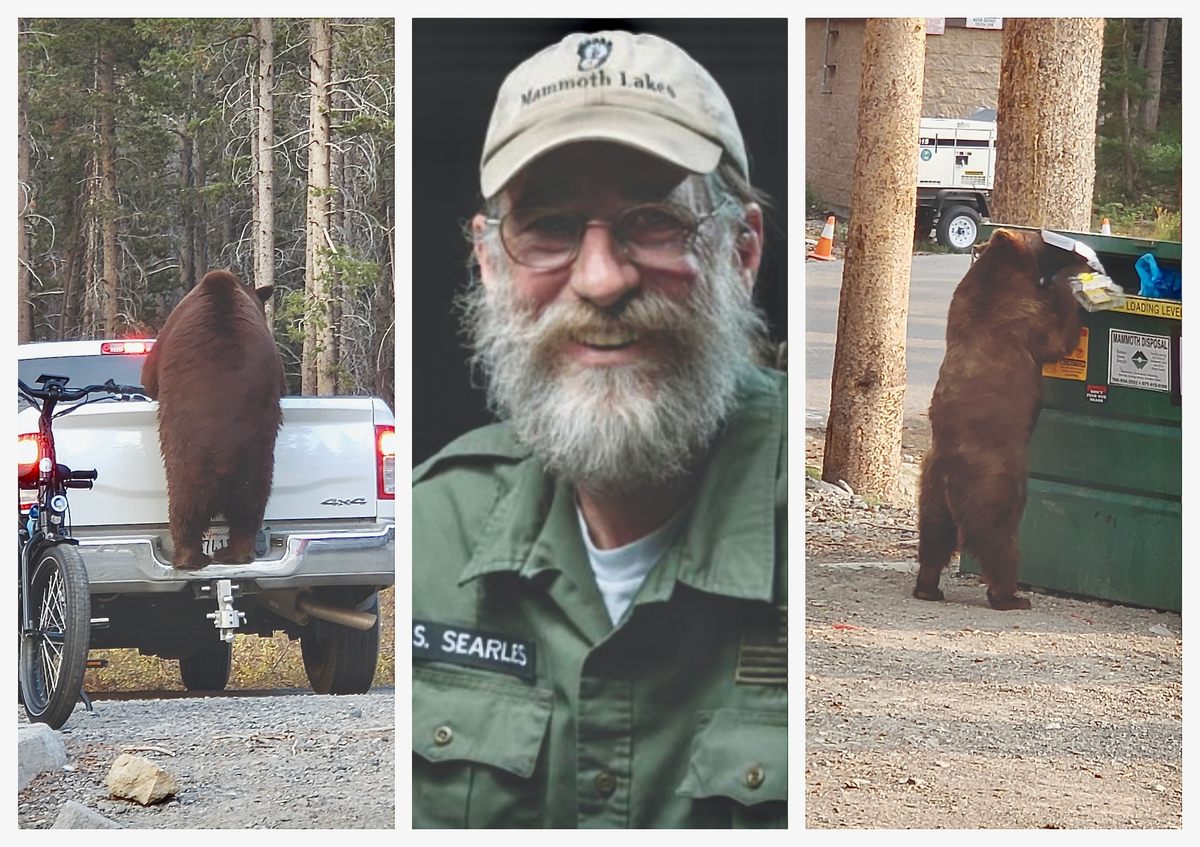

Animal Planet’s ‘Bear Whisperer’ shares how the California town copes with both dumpster-diving bears and human party animals.

Excerpted and adapted with permission from What the Bears Know: How I Found Truth and Magic in America’s Most Misunderstood Creatures, A Memoir by Animal Planet’s “The Bear Whisperer,” by Steve Searles and Chris Erskine, published October 2023 by Pegasus Books. All rights reserved.

In the late 1990s, the snow-globe village of Mammoth Lakes, California, hired hunter Steve Searles to shoot and kill 16 troublesome bears. In the course of his preparations, the bears won Steve over, and he soon developed nonlethal tactics to keep them out of harm’s way.

In time, he became a local folk hero, a reality TV star, and a nationally recognized expert in the humane treatment of animals. Don’t tell Steve that. The gruff outdoorsman will quickly remind you the bears are the only heroes in this mountain hamlet five hours north of Los Angeles. The most important life lessons come from them.

The more I learn about the bears, the more I learn about human nature and this quirky mountain retreat. We’re not a wholesome, Little League town. The snow is dry and glistens like sequins. But that doesn’t translate into anything pure.

You come to these silver hills to get your party on, to get laid, to get your rage, and to get out. Visitors come for fun, then they return to Brentwood or Newport Beach, after blowing off steam, and blowing off the outstanding warrants. Out of sight, out of mind.

“Come for vacation, leave on probation,” a local saying goes.

At the police headquarters, I once saw someone call up all the outstanding warrants; there were 6,000, an astounding number for a four-square-mile town with 7,000 official residents, though I’ve always suspected that 4,000 is probably a more accurate number, if you’re counting permanent residents.

Many of the locals work for the government—local, county, state, and federal; others work at the hospital, at the ski mountain, or in local businesses. Cooks, servers, lift operators, ski teachers make up a significant chunk of the population. Mix in the well-off folks who drop in for a weekend here and there, and you get a diverse and dynamic populace.

Every little town has a dark side, mountain towns maybe more than most. All told, this is a marvelous place to make a life. For all its quirks, Mammoth Lakes is a life-changing paradise for a guy like me, who feels privileged and proud to have a role in daily life here.

Working with the bears in a public position changes my stature, for the good and for the bad. Going in, I know all the officials, the residents, the cops. And, it comes as no surprise that, in the early years of working with the bears, residents stand out on their porches and mock me.

“Bad bear! Bad bear!” they echo, as I scold a bear and her cubs down a street. That is my mantra, my one hit song: “Bad bear! Bad bear!”

Think of the vocabulary of a good dog: “Get in the car.” “Off the couch!” It’s got to be 40 words. Bears’ instincts and capabilities are higher than your dog. No surprise to me that the bears could pick up on the words I used. Hand signals are a big part of my arsenal, too. As with pets, a voice command accompanied by a gesture is far more effective than a voice command alone.

One bear I work with, Rasta, has gone completely deaf. She’s an odd-looking bear, as big around as she is tall, with an abundance of guard hairs, the thistle-like protective hairs. We call her Rasta, because when she turns to show her profile, these wild hairs show up, hanging down her sides, making her look she has Jamaican dreadlocks.

She’s a good bear, a bear everybody likes. Tourists can’t rattle her, no matter how silly their behavior. A patient and slow-moving bear, Rasta has a routine like clockwork. Grew up here, knows her way around. Rasta doesn’t care much for exercise, kind of a slug, actually. Her favorite food court is the shorelines of our lakes, where anglers leave stringers of fish at the water’s edge. She enjoys countless meals that way, for not much effort. No one complains. The stocked lakes feature beautiful fish, but the trout are farm raised, fed on cat kibble, hardly the most organic diet. Sure, Rasta baby, have yourself a few cat-kibble trout. Chef’s kiss.

Well, in the six or seven years she’s around, we realize that we are having to raise our voices to Rasta, as you do with Grandma and Grandpa as they age, find their good ear, repeat yourself, almost yell to be heard. It’s very rare for bears to lose their senses like that, the way we do. For bears, there is very little physical decline—nature won’t tolerate it. Once an aging bear can’t fend for herself, off she goes into the forest to die or be killed. Older bears just wander off and don’t come back.

Not only is it unusual to come across a deaf bear, but Rasta’s hearing loss is incremental; takes us a while to realize she responds only to hand signals, not voice commands. I learn to point this way and that, to guide her away from trouble. If I see her heading to a camp or a group of fishermen, I traffic cop her around.

One day when I’m not around, Officer Doug Hornbeck finds Rasta locked in a staircase at an apartment complex and uses the same hand signals he’d picked up from me to guide the bear to freedom.

“Hey, Steve, you won’t believe what just happened…” Hornbeck says the next time he sees me.

Like watching your kid grow, in the moment we don’t always appreciate all this wildlife work. But when you look back at the magic little moments and the milestones, with the clarity that time can offer, you think: Wow, that actually happened? In this case, we actually learned to communicate with a deaf wild animal.

So, early on, the obvious revelation: Why wouldn’t we use language to coexist with the bears, one of the smartest animals in the world? Instead, we take the low road that we often do when faced with new situations we don’t understand: We panic, we throw stones, we yell, we call 9-1-1.

All the years, I worked with bears, when I’d say “Good boy, good boy,” people would laugh and wonder why I would do that; they’d think I was a fluffy weirdo—like those folks who pet whales. You’re with a bear for 20 years, you learn to communicate…the good, the bad.

When I roll through a neighborhood in my truck, making my rounds, they spot me and yell “Bad bear!” like some sort of battle cry. Over time, “Bad bear!” goes from derisive to an affectionate appreciation of my work. They are aware and grateful for the progress we’d made together so quickly. Their love and fascination with bears wins out. They buy in, even if their normal default emotions are ridicule and a general distrust of authority figures of any kind (you have to kind of admire that). This love and fascination doesn’t just apply to bears; it starts to apply to other wild animals. It even streams down to the chipmunks, porcupines, all the creatures we took for granted. They call me the Bear Whisperer? We all are bear whisperers. Earlier in human history, humans knew the right ways to deal with wild animals. Your great-grandparents likely knew not to pet a buffalo or hand-feed bears or leave food lying around for the raccoons. They were better with animals. They lived among them in rural areas. That’s what we’re after here.

The whole paradigm change happens in a short period. It is a chapter out of a storybook.

Doesn’t hurt that I am so much like the residents here—a wiseguy with a bit of an attitude, always quick with a flip remark. My stewardship of these bears amuses them. To their minds, I am like a pied piper of an odd and hairy cult.

“Bad bear!” they’d shout, then point directly toward me. I’d smile.

Tricky audience, for sure—a crusty, hardworking demographic with a gift for a snide remark. At first glance, Mammoth Lakes looks like an overly gentrified Swiss village, a slick snow globe. In truth, it’s a little more like the morose and secretive town in that eccentric TV show Twin Peaks.

In 2011, a popular daycare provider is sentenced to sixty years in prison after pleading guilty to four counts of child molestation.

My point is that you think you can escape to the mountains and leave creepy human behavior 300 miles away. You can’t. Where there are humans, there will be creepy human behavior.

The town consists of two major groups, the locals and the tourists. They’re codependent and mostly tolerant of the other side. It’s a class clash. Also, a values clash. Also, I think each side envies the other a little bit: The tourists envy the townies’ outdoorsy lifestyle; the locals envy the tourists’ heaping gobs of vacation cash. To be fair, many of our visitors are just as hardworking as I am, or more so. They’ve brought the family up and are trying to stretch a buck, just as I would. As the saying goes, skiing is like standing in a cold shower and tearing up $100 bills. I am grateful for their presence. Folks like that built this place.

The party boys are another story. I don’t have too much in common with the ones who drink too much tequila and suddenly decide to jump naked (and steaming) from the Jacuzzi into a nearby pile of snow, amid the cackles of their pals and sweethearts. You see stuff like that all the time up here—this Jacuzzi-to-the-snow stunt. Hey, what do I care? If it restarts the guy’s engine, fine.

It’s certainly better than some of the things they could be doing. There are plenty of drugs up here, as there are in any raging party town.

The locals? A little crabby, truth be told. It’s a hard life. Forty miles south, in Bishop, the elevation is low enough that the big snows don’t pound them. By comparison, we’re the North Pole.

In a typical year, there is so much snow that you have to shovel your roof to keep the rafters and trusses from collapsing. You open a door after a big blizzard to find the doorway filled with a wall of snow, a flat and perfect rectangle except for the hole the doorknob left. You’re literally snowed in, yet the dog needs out and the kids have to get to school. Start digging, Mom and Dad. Oh wait, the shovel’s outside on the porch? Of course, the shovel is outside. Who brings a shovel inside a cabin? Well, in Mammoth the veterans do. So you’re ready to dig yourself out of the next blizzard.

As noted, we even wax our shovels, as you would a surfboard, warming the metal blade over the stove and rubbing the butt end of a candle across it. With the wax, the snow slides right off, making the grueling task a bit easier, as we move tons of the stuff by hand each year.

I once shoveled off my home’s steep sheet metal roof, walked along the ridge line clearing a row at the very top. As I learned in my snow removal days, once you clip that very top row of snow, gravity carries both sheets of snow gliding to the ground. So I’m walking like a duck with both of my size 15 boots through the three feet of rooftop snow. Along the ridge line, I’m shoveling a line all the way down the ridge when a sheet of the snow begins to go, carrying me with it. Rather than fight it, I sit with my feet facing down, as you do if you go overboard while white-water rafting, and let go of the shovel. The mini-avalanche sweeps me past a protruding vent pipe I can’t see, which fillets my hand open like a fish. Meanwhile, the shovel lands blade first in the drift at the side of the house, so that when I fall on it seconds later, the handle whams me in the ribs, like a bad pole vault. Dazed and bleeding, I stumble a few steps, then fall eight feet from the drift to the pavement.

Oooooof. “Debs! Help!” A bad day, to be sure, including two hours in the emergency room getting stitched. Almost a cartoon moment, this sequence of lousy luck. Still, typical of the types of mountain hardships we constantly face.

Car doors freeze shut, and once inside, the engine won’t crank. Twenty-five-foot plow piles block drivers’ vision at intersections. Most years, it snows so much crews have to load it into trucks and dump it on the outskirts of town, because there’s nowhere else in the village for the big plows to push it out of the way.

Each weekend, armies of L.A. people descend, filling the restaurants, emptying store shelves, and turning the town’s only supermarket into a version of Mardi Gras. Hooray, that’s why we’re here. Their bread is our butter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook