Meet Rufus Harley, the First Jazz Bagpiper

Jazz met the Highlands when Harley met the bagpipes.

Like most Americans alive at the time, Rufus Harley was transfixed by the November 25, 1963 reporting from John F. Kennedy’s funeral. America had lost its leader, and with ears pressed to radios or eyes turned to television screens, each person witnessed the end of a tragic turn of events. In the background, Harley heard a low sound. A deep droning echoing over the sadness. Harley, a Philadelphia jazz musician who at that point had been playing the flute and saxophone, felt something stir in him. It wasn’t just the sadness of the day, it was that sound.

Those low moaning notes falling over the procession were the exact sounds he had been trying to capture in his music. “When I heard and saw the Black Watch Bagpipe Band marching across the funeral grounds,” Harley said in a 1982 interview, “I was very impressed with the sound of the instrument. I could understand it.”

Understand it? Sure. Reproduce it? Well. He tried to make his horn produce that sound. Tried and failed. There’s nothing like the real thing, and so that winter, Harley bought a set of bagpipes for $120 from a pawn shop, making him the first jazz musician to make the Great Highland bagpipes his primary instrument.

“The pawnbroker thought I was crazy,” Harley recalled in that same interview. “In fact, every musician in Philadelphia thought I was crazy.” It didn’t matter, though. Harley was determined. He researched the bagpipes, finding out that, despite being most widely known as a Scottish instrument, the bagpipes have a worldwide reach. The first written evidence of the bagpipes showed up in first-century Greece. Over the centuries, versions appeared in Spain, Greece, North Africa, and the Middle East. History and relative oddity aside, the big question for Harley wasn’t why play the bagpipes, it was how. The answer was simple: practice. Harley enlisted the help of Dennis Sandole, a musician and music teacher who had been working with him for 20 years.

Adapting the bagpipes for jazz meant that Harley would have to approach the instrument unconventionally. As author Daniel Goldmark explained in his essay “Slightly Left of Center,” Harley tuned his drones—the pipes that produce harmonizing notes—to F and B-flat, a switch from the instrument’s more common tuning, so that he’d be able to play with other jazz musicians. The bagpipes’ chanter also presented a problem. This pipe, played with two hands, provides the melody but it only plays nine notes. Probably not the ideal set-up if you’re trying to get on stage with someone like John Coltrane, considering Coltrane wielding a tenor sax could play over 30 notes. Add a trumpet player to the mix, and that player gets over 40 notes of his own to play around with. Those nine notes need to do a lot of work.

If all of this sounds hard, well, it wasn’t, at least not for Harley. He was able to adapt his playing in about six months. He had done it. He was a jazz bagpiper.

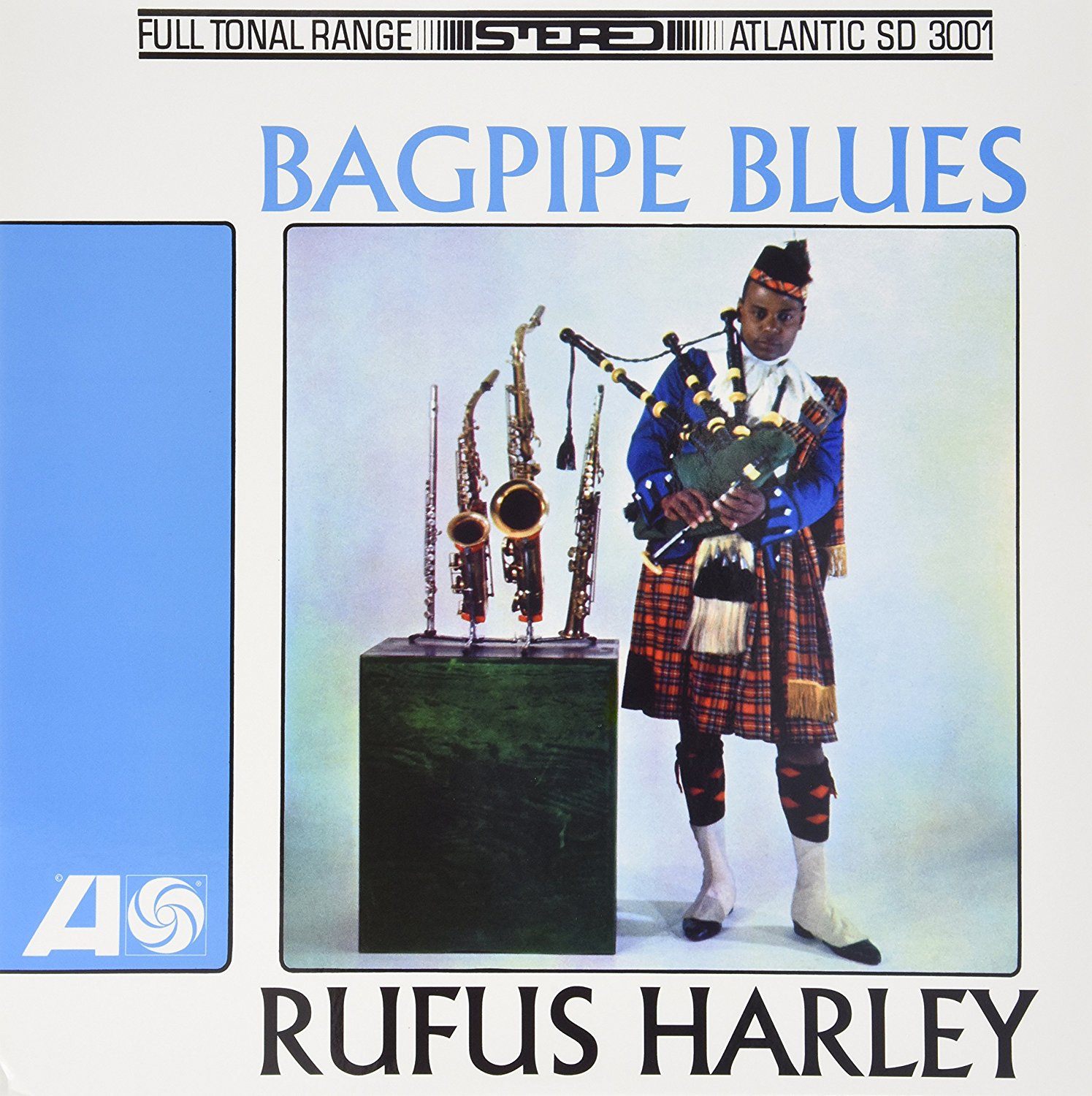

Oddly enough, however, the bagpipes weren’t an easy sell. Harley was finding it tough to get into the jazz clubs to play. Club bookers and owners thought the whole thing was a gimmick. He wasn’t really going to play jazz, was he? On that? Who did this guy think he was anyway? At the point of his bagpipe awakening, Harley was only 27 and had never released an album, so convincing club owners that he was serious was even more difficult. But he kept at it, and by 1965 he’d caught the attention of Joel Dorn, a young Atlantic Records A&R assistant. A year earlier, the label had tasked Dorn with finding a new talent, someone who’d never lead a band before. He brought them Hubert Laws, a jazz flautist. Dorn was nothing if not unconventional, so for him Harley was a natural next step. In 1965, Haley released his first album, Bagpipe Blues, and it was a hit—for a bagpipe jazz record. Dorn recalled in an interview that appeared in the liner notes of a 2008 Atlantic Records jazz compilation: “[T]he bagpipe record took off! Now when I say it took off, it sold five, six, thousand copies. But for a jazz album by an unknown artist, and one who played the bagpipes? That was a big deal.”

The album featured seven tracks, a mix of traditional Scottish songs, spirituals, show tunes, and originals, with Harley on bagpipes for just three of them. But they’d done it. Harley and Atlantic records had released an album that would forever require people to say bagpipes and jazz in the same sentence. This excitement was probably tempered by the reviews. “No doubt it makes a good gimmick by the decade’s standards,” said the Saturday Review. “Not the greatest jazz you ever heard, but unmistakably jazz,” said Melody Maker. And most troubling, “screeching and barbarous,” said Newsweek.

As unconventional as the instrument may have seemed to reviewers, it’s not like experimentation in jazz was new, especially not at this time. World music was intertwining with the genre in exciting and innovative ways, and instruments most would overlook in the jazz world were making an impact. Saxophonist Yusef Lateef was playing with Chinese and Middle Eastern sounds, and harpist Dorothy Ashby was bringing the orchestra to the jazz club. “Harley was in the right place at the right time,” says jazz radio program director Matt Fleeger. “Living in Philadelphia, he was exposed to a lot of jazz music and jazz luminaries at a time when jazz was really important to the community. It was time of a lot of experimentation, and instead of reaching for African or Asian influences, Harley went European.” The bagpipes were a means for him to play with sounds, genres, and harmonies.

Harley hated being considered a gimmick. As he told Ebony magazine in 1969, the bagpipes were anything but; they helped him “discover my identity.” Taking up the instrument marked huge changes for Harley. He became a vegetarian once he started playing, noting that his diet made it easier for him to blow into the bagpipes: “[I] had to make a choice between the meat and the bagpipes. I, of course, chose the bagpipes.” He also began using the instrument as a teaching tool, considering it another part of his larger philosophy of empowerment and cultural awareness.

Harley followed up Bagpipe Blues with 1966’s Scotch and Soul. Although none of his albums were burning up the jazz charts, his 1967 album A Tribute to Courage did manage to find its way onto the R&B charts. He started making appearances on talk shows and variety shows (most were of the “Guess what this guy does for a living?” type). He started touring, hitting the jazz festival circuit worldwide, including a performance at the Newport Jazz Festival in Rhode Island.

Harley continued playing the bagpipes, recording and playing live, up until his death in 2006 and even added another notable entry on his resume along the way—midwife. He helped deliver all nine of his children at home. Harley’s jazz career wasn’t the normal path, but what’s normal, anyway? He pushed the boundaries of jazz like few others, but what’s jazz, anyway?

“When people hear Harley for the first time, the reaction most people have is, ‘Is that a bagpipe I’m hearing?’ Fleeger says. “He played it so differently. Like a spiritual jazz thing. Laid against traditional jazz, it really surprised listeners. He took something [unusual] and assimilated it into the program. If you can do that with bagpipes, you can do it with anything.”

Despite the initial shock of seeing Harley with the bagpipes, his place in music history has been solidly confirmed with guest spots on recordings by experimental singer Laurie Anderson and hip-hop band The Roots. His genre/continent/expectation crossing music was a surprise to everyone—except Harley, that is. “There’s only one thing going on,” he told Ebony magazine. “And all you’ve got to do is dig it.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook