Found: A 50-Year-Old Scientific Message, Stuffed in a Bottle

Thousands were cast into the waves in the 1960s, and one turned up in Texas decades later.

Candy Duke and her husband, Jim, spend their weekends combing for treasure. They bring a lunch and make a day of it at the Padre Island National Seashore in Texas, keeping their eyes peeled for shells, sea glass, and bottles—some green, some brown, some barnacled, some clear and wave-beaten. Candy estimates that they’ve stumbled across at least 100 little glass vessels, plus hydraulic jacks, trash cans, and “I can’t tell you how many nets that have come off of who knows what.” Some of the haul goes straight into the trash—just to get it up off the sand—but they salvage their favorites and arrange them across their yard in Corpus Christi.

One recent Saturday, Jim came across a bottle with something to say.

Through the scuffed glass, they could make out a yellowing piece of paper—almost the color of the sand. It was wound into a tight scroll, and it bore an instruction scribbled in big, capital letters: “BREAK BOTTLE.”

But, Candy says, the couple had no plans to do that. They figured, they collect bottles—they don’t bust them. So she and Jim set out to free the thing inside without destroying the rest of it.

The couple took the bottle home and got to work, broadcasting their efforts on Facebook Live. Jim went at it with a standard wine bottle opener, while Candy’s brood of birds—several dozen parakeets, lovebirds, cockatiels, finches, and canaries that she raises for a local pet store—chirped loudly in the background, and their deaf rescue cat, Handsome, preened, disinterestedly, on a chair. “It’s a real hard rubber cork,” Jim said, as Candy filmed. He needed to put more muscle into it, and stood up to get more leverage. “By George, it may be coming,” he said, cranking his wrist. He grunted a bit. The thing didn’t budge. “Come on, baby,” Jim muttered to the cork, scrunching up his face as he tried to wriggle it free. “Thank goodness there’s no wine in there,” Candy said. “We’d all be crying at this point.”

They finally speared it with an ice pick. With a little shimmy, the stopper came loose. Since the paper had been shoved all the way down to the bottom, they needed to use tweezers to fish it out. As they reached for it, Candy and Jim wondered if they’d won something—a cruise, maybe, or free tacos?

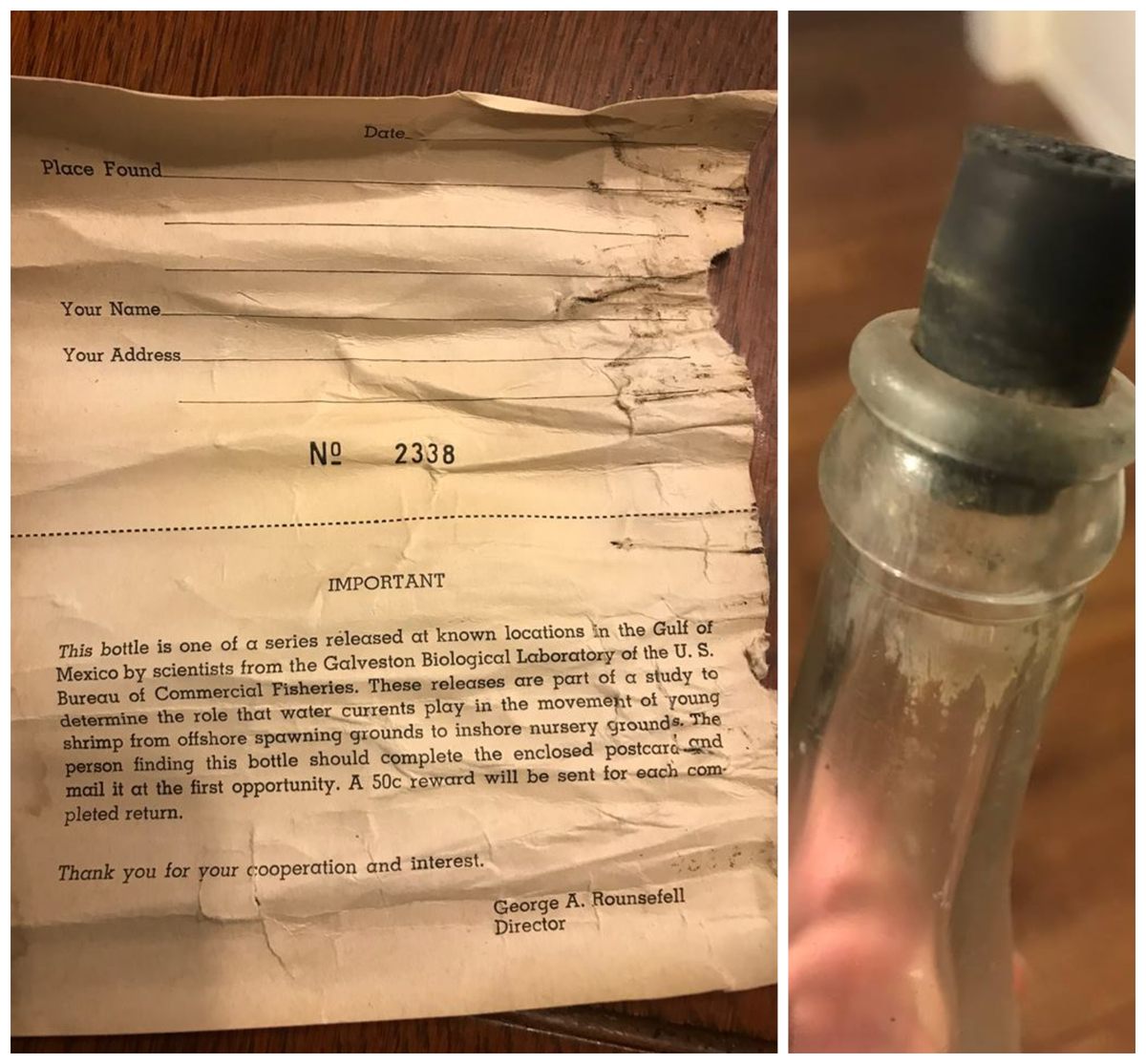

Not quite. When they liberated the paper and unrolled it, they discovered that it was a postcard—still nice and dry—to be filled it out and mailed back to the U. S. Bureau of Commercial Fisheries. Whoever found the bottle was supposed to jot down the date and place they’d encountered it, because the office was trying to track the effect of surface currents on young shrimp moving from “offshore spawning grounds to inshore nursery grounds.” Anyone who returned the postcard would receive 50 cents for their trouble.

On the Facebook video, Candy seemed a little let down. The couple signed off quickly, and maybe a little sheepishly. It was no cruise, or even a plate of tacos. “It was kind of like we had built up all this drama, and it was just this thing—50 cents,” Candy says now. But, off camera, she filled the postcard out anyway, made a keepsake photocopy, and sent the original on its way to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), which inherited many of the duties of the old bureau.

She soon heard from Matthew Johnson, the acting lab director at NOAA’s Galveston Laboratory Southeast Fisheries Science Center, who shed more light on what she’d found. This little bottle had taken a long swim. It been in the water since 1962 or 1963, one of 7,863 that had been released in clusters across the Northwestern Gulf of Mexico. Of these, 12 percent were recovered within 30 days of being set adrift, according to a 1979 NOAA report. “A lot of that stuff disappears into the abyss,” Johnson says.

It turned out that Candy and Jim had happened upon the legacy of a citizen science project that wrapped up decades ago. At the time, unleashing a school of bottles and asking people to report their sighting “was a cutting-edge way to figure out what’s going on and relate back ocean currents to animal abundance,” Johnson says. It was a way of retracing the buoyant journey from point A to point B. Johnson has worked at NOAA for four years, and his wife has been there for 20, and this find was definitely out of the ordinary. “We have not seen one of these recovered at all in a long time,” Johnson says.

This new data wasn’t useful, really, so many decades after the project was over—but a deal was a deal, and Johnson offered Candy the 50 cents anyway. (She declined.) The bottle is still a treasure, though, and she plans to store it in a shadowbox, safely away from the waves.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook