How One Wyoming Mule Deer Won Friends and Influenced Science

Jo the deer offered researchers a look into migrations and how long it takes deer to visit a forest after a fire.

This piece was originally published in High Country News and appears here as part of our Climate Desk collaboration.

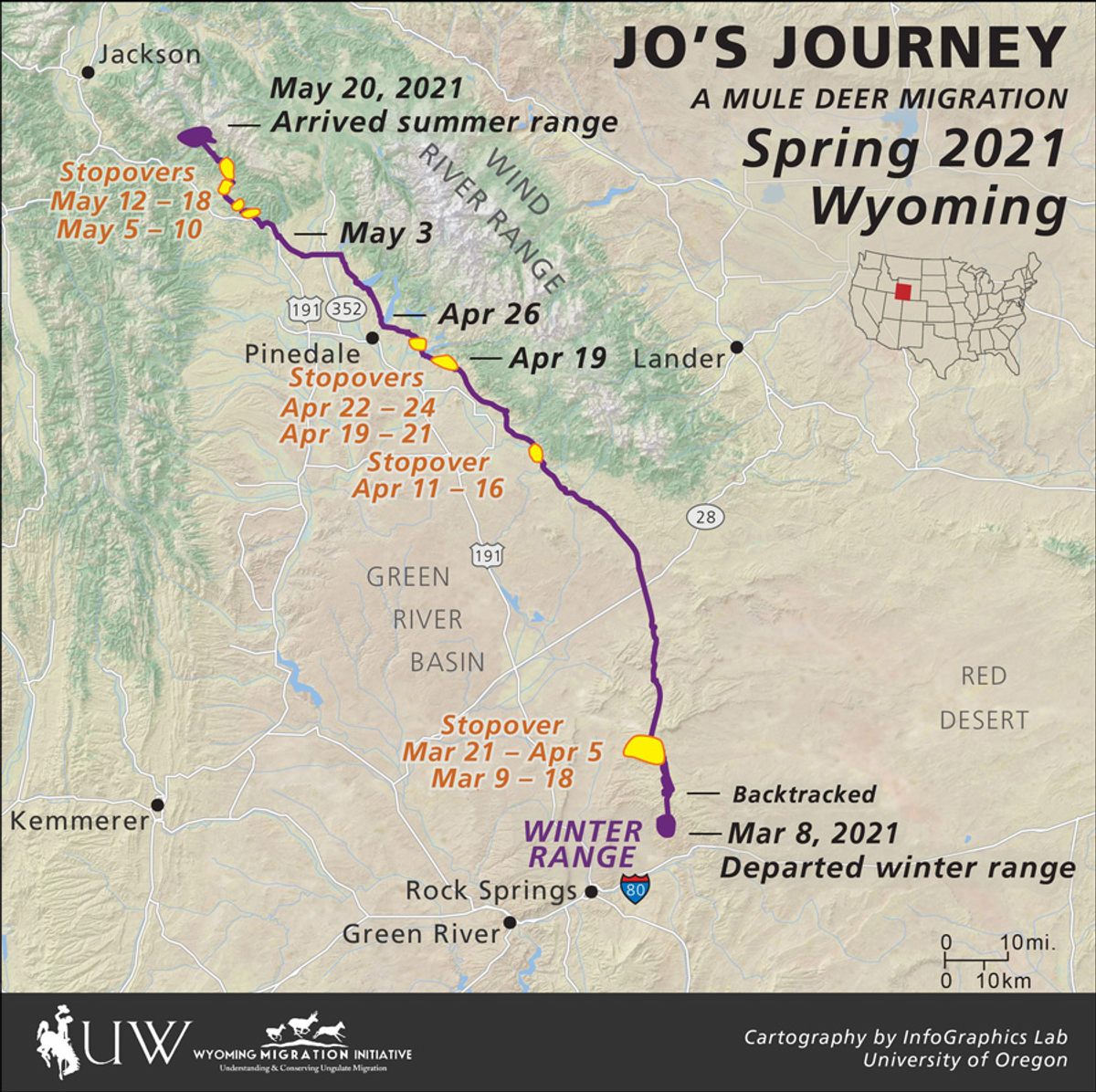

Every spring, a herd of more than 1,000 mule deer leaves its winter range in Wyoming’s Red Desert in search of bountiful grasses and forbs. Some of the animals travel far, heading north up to 155 miles to the mountain slopes of the Hoback Basin, while others stay closer to home. They reconvene in the fall to ride out the winter in the Red Desert.

But one deer—Jo, short for Journey—never made it back to the Red Desert this winter. Researchers announced her death in mid-March after her fans kept asking, “Where’s Jo?” Although it’s hard to pinpoint a cause of death without a biologist immediately at the scene, her collar stopped moving last July. When scientists located it, they also found evidence of bear scavenging. Now they’re looking back on her life and discussing just what made this deer so special: how she offered a window into how, and why, her herd fans out across the Wyoming landscape.

Researchers collared Jo in 2018 and, in the spring of 2020, introduced her to followers of the Wyoming Migration Initiative, a University of Wyoming-based collaborative of biologists, photographers, mapmakers and writers studying ungulate migrations. Research monitoring deer in the Hoback Basin started almost a decade earlier, yielding the data necessary to designate a 160-mile, 830,000-acre migratory corridor there. Mule deer populations throughout the state have been declining since the ’90s, and researchers are hoping to learn how to better protect and conserve their populations. In 2020, wildlife agency officials estimated that there were 330,700 mule deer in Wyoming — 31% below the target of 476,600 deer.

Other humans followed along as, for years, Jo moved between the Red Desert and the wildflower-dotted slopes of the Gros Ventre Range. Jo’s journey from basin to high country took about four months and entailed crossing rivers, bounding through sagebrush, raising fawns, and avoiding highways, energy development and fences. YouTube videos and social media posts chronicled her travels, and followers often left comments, writing, “Thanks for making it possible for us to travel along with Jo!” and “Safe travels!”

Reactions to Jo’s death ranged from disappointment (“Bummer. She provided great intel and was fun to follow”) to emotional (“Rest in peace sweet girl. May your offspring flourish in this place we all love”) and matter-of-fact (“And so nature goes.”)

“Her story is done, but her legacy will continue and so will the research,” said Anna Ortega, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Wyoming. Jo—an excellent representative of the herd’s long-distance migrants—gave Ortega and her colleagues a unique opportunity to study ungulate movement post-wildfire. Celebrity animals, like Jo, are also a powerful way to pique interest in migrations. “It’s more likely that someone will be invested in, say, Jo the deer, than several thousand animals moving,” said Kristin Barker, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of California, Berkeley who studies elk in Wyoming. “It helps people connect more personally to something that would otherwise be abstract.” Barker herself was not involved in the Red Desert mule deer research.

A few months after Jo was born, lightning ignited the Cliff Creek Fire, which burned over 20,000 acres. Ortega found that the deer in Jo’s herd avoided the dense conifer forest before the fire, perhaps because a lack of sunlight meant fewer plants to eat. But afterward, Jo and others swept into the area, drawn by the lush new plant growth. “That suggests that wildfire does open up habitat that was once unfavored by mule deer or elk,” Ortega said. Jo raised several fawns on the vegetation that sprang up post-fire.

Ortega is learning that where, and how rapidly, ungulates return to a burn scar is determined in part by burn severity. The animals tend to avoid extremely scorched areas at first, preferring places that experienced less intense fire activity, since they have the forage deer need. But after a year or two, once plants start to regrow in badly burned areas, ungulates flock to them again.

Jo’s own journeys added context to the movements of the greater herd. “When you look more closely at the individual level … you get a more nuanced understanding of how animals actively perceive and respond to their environment,” Barker said. Jo’s herd showed researchers that migration is key to survival, even when the distance traveled varies. “The thought is that migration diversity exists because there are some trade-offs in survival and reproduction,” Ortega said. “It’s similar to not putting all your eggs in one basket.” For example, deer that travel longer distances gain more fat over the growing season, but deer that migrate medium and shorter distances are more likely to see their fawns survive to fall.

One animal, known as Deer 255, wowed researchers with her record-setting migration — 242 miles one way, the longest documented land migration in the Lower 48. She helped set the upper bounds of the herd’s migration, but did not serve as the best proxy for understanding the majority. Most deer travel far, but not that far. “We haven’t captured anybody like her,” Ortega said. “She’s an anomaly and an outlier. But when we look at Jo, she’s representative of all the long-distance migrants.”

Although Jo’s journey ended last summer, others will soon begin. Spring is coming, snow is melting, plants are emerging, and within the next month or two, researchers will be watching to see where the next generation of mule deer go.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook