It was a two-man job. Bill Blair Sr., in a ‘39 Ford loaded with white liquor, hung back, while his friend Elmer sped down winding North Carolina roads as though he was riding the devil’s horse. “Agents would get after Elmer and chase him,” says Bill Blair, who inherited Blair Sr.’s name and love for racing. “My daddy would come down the road with nothing to bother him.”

The agents were from what’s now known as ATF: the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives. But on this occasion, Elmer hesitated at a fork. Instead of picking left or right, he slid into a maple tree. According to Blair, Elmer shimmied out the window and hid. The agents, who assumed he’d run for the tree line, started shooting. “Daddy rolled up and he saw all that and slowed,” says Blair. “Elmer came out of that tree like a squirrel, opened the door, hopped in, and said ‘Let’s get out of here!’”

They had 40 miles to go and were weighed down by 120 gallons of white liquor. The ATF caught up to Blair Sr., inching next to them on the backroads. So the haulers tapped the government vehicle off the road and kept driving until they came to a row of cabins along the Dan River. The hideouts, Blair says, were big enough to drive inside, then put the doors down behind you.

This is one of many stories Blair grew up hearing from his father about his moonshining days. While the story, like many family legends, is difficult to verify, it fits with many other accounts. The almost-friendly rivalry between cops and bootleggers was such that the Atlanta police were quoted as calling moonshiner Roy Hall a “genius at the wheel” because of his ability to outrun the law.

Blair’s father started hauling moonshine in 1932, trying to liven up his dairy farm life in High Point, North Carolina. According to his father, he was “born to be hung.” Blair Sr. was a gearhead, a moonshiner, and a pool shark, and like so many trippers who raced illegal liquor from the swamps and forests of North Carolina to cities and mill towns, he was getting all the education he needed to become a stockcar driver.

The stakes of these races against the law were high, but many early NASCAR drivers got their start tripping whiskey down dirt roads in the South. While NASCAR downplayed it for generations, these are the sport’s roots. Names like Junior Johnson or Lloyd Seay are almost as synonymous with NASCAR as they are with white lightning and bootlegging.

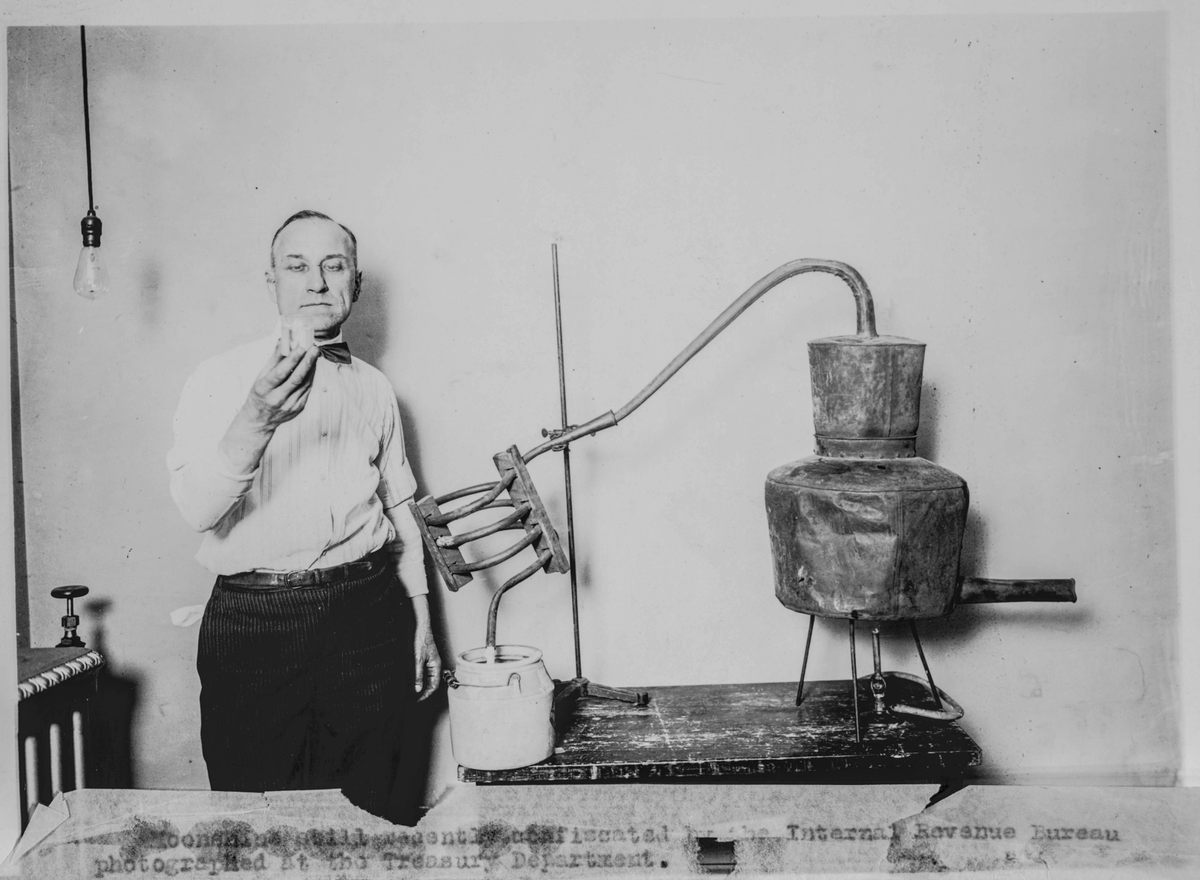

Most people associate moonshine with Prohibition, but Americans have been making booze in the backwoods since there was a tax man come to collect on it. The United States wasn’t even a decade out of the Revolutionary War before Alexander Hamilton proposed a tax on domestic spirits—in other words, whiskey. Many farmers living near the Appalachian Mountains converted extra grain into spirits, and they hated the tax so much that they tarred and feathered collectors. President Washington had to send 13,000 troops to quell the rebellion.

Officially, the rebellion collapsed. But people continued making moonshine in the Appalachians. As more and more states prohibited alcohol in the 1900s—a prelude to national Prohibition in 1920—it was old hat for families who had been selling boozy wares tax-free for generations. “Most people in rural areas didn’t see [making moonshine] as illegal,” says Daniel S. Pierce, author of Real NASCAR, a book about the origins of the sport. “It was a violation of federal law, but that didn’t count.”

In the early days, moonshine was sold locally, to friends and family; Pierce says it’s unlikely that people moved moonshine more than 20 or 30 miles by wagon. It might have remained a small, lawless enterprise if Prohibition hadn’t coincided with the advent of mass-produced automobiles. Bootleggers replaced 40 gallon stills with stills that could hold up to 1,000 gallons and hid them in Appalachia’s mountains, swamps, and thick forests. The local geography lent itself to secrecy and speed. No matter how swampy the terrain, there was usually a road nearby which led to customers. By 1934, Neal Thompson writes in Driving with the Devil, as many as 35 million gallons of moonshine were produced nationwide.

Blair Sr. was just one of many young men whose love of cars and thrills got illicit booze into customers’ hands. While he and Elmer partnered to draw the ATF away from the real cargo, others turned off their lights and drove in the dark along lonely and jagged side roads. Moonshiner Smokey Purser used disguises from wearing a priest’s collar to writing “fresh Florida fish” on the side of his vehicle and throwing in some dead fish for good measure, Daniel S. Pierce writes in Real NASCAR. Trippers drove Ford V-8s, often modified with additional springs to keep contraband-loaded cars from sinking so low they tipped off authorities, and learned maneuvers like the “bootleg turn,” a high-speed dance of breaks and gears that turned the car 180 degrees.

“Moonshiners put more time, energy, thought, and love into their cars than any racers ever will,” moonshiner and NASCAR driver Junior Johnson once said. “Lose on the track and you go home. Lose with a load of whiskey and you go to jail.”

Auto racing was then dominated by AAA, which controlled the largest race, the Indy 500. “A Kentucky Derby-like air of of aristocracy hung over most races,” Thompson writes. “Fans were typically men, wearing suits and bowlers and smoking pipes.” Southern stockcar racing, with its desperado drivers and cars modified for whiskey tripping, was distinct. At first, races were informal affairs among drivers, but they quickly attracted spectators.

Early stockcar races were messy affairs with scrappy drivers and scrapped cars. Country drivers didn’t have automobiles crafted for racing; they were stock, no different from a family car, other than perhaps some modifications under the hood. Blair Sr., like many drivers of his day, purchased his car from a local junkyard dealer.

“The do-gooders didn’t go to stockcar racing,” Blair says. “You’d need to take a bath because it changes your shirt from white to red.”

On race day, you could see the dust cloud a mile away. Mud caked onto windshields and drivers put screens in front of radiators to protect them from dust. There were so many rocks on the track that racers scoured junkyards for new windshields. Drivers didn’t have jumpsuits, but wore primitive helmets and tied handkerchiefs around their faces like bank robbers. Lacking seat belts, they sometimes tied themselves in place with rope. “My daddy would spit red dirt until Tuesday,” Blair remembers. If your hands had blisters, you’d pop them until you had two bloody hands.

“He did it because he loved it,” Blair says of his father. “There was no money in it.” Drivers might collect $75 for winning, or they might find that a promoter ran off with the purse. There weren’t sponsors, Blair says. “White liquor was his sponsor.” Pierce writes that haulers could make as much as $450 a night driving moonshine well into the 1950s—income that was, of course, tax-free.

Blair’s father raced, he says, because “it made you somebody important.” Whether Blair Sr. was at a racetrack or visiting a small town, people stopped to talk to him. “It was like he had an entourage.” The family home was close to racetracks, and since it wasn’t easy to find a motel, people would stay at the Blair house in the grove of pin oak trees near the dairy. Blair remembers his mother making breakfast for the racers.

These races were gaining popularity when World War II hit. Many young men went off to fight or work in shipyards, and gasoline rationing was a temporary stop sign for automobile racing. But when the war ended, a former racer turned promoter known as Big Bill France changed the sport forever.

Until France came along, tracks made their own rules, and a hodgepodge of promoters, track owners, and sanctioning bodies put on each race. The AAA sponsored several stockcar races, Thomspon writes, but stopped in 1946, stating, “The Contest board is bitterly opposed to what it calls ‘junk car’ events.”

France had a chip on his shoulder about the respectability of races. According to Pierce, France’s life’s mission was to “raise the level of NASCAR and take it beyond a working class thing—increase the appeal to families and women and the middle class.” France began promoting races, taking money at the door, and offering bigger purses to attract the best racers. He created an organization called the NCSCC that paid drivers for each victory and offered a $1,000 prize to the driver with the most points from NCSCC races.

The crowds grew larger under France’s watch. People like Raymond Parks, a moonshiner who was the first team owner in the sport’s history, hired some of the best early racers, and new racetracks and speedways were built left and right. In 1947, the Blair family opened the Tri-City Speedway in North Carolina. The money Blair Sr. used to build that track wasn’t racing money; it was liquor money.

In 1947, a meeting of drivers, mechanics, team owners, and others important to the sport’s early success led to the official creation of NASCAR (renamed from NCSCC)—all under Bill France’s private ownership. While the crowds were good, France still wanted to attract the country club set to stockcar racing. In fact, NASCAR didn’t lift a rule that prevented liquor companies from sponsoring cars until 2005.

Yet moonshiners still raced. In NASCAR’s inaugural year, Blair Sr. won a championship race in Danville, Virginia, and would win another three among the 123 strictly stock races he participated in between 1949 and 1958. When Tom Wolfe famously wrote an article about Junior Johnson for Esquire in 1965, raising NASCAR’s profile tremendously, he highlighted Johnson’s history in bootlegging, including an arrest at his father’s still.

Though the NASCAR Hall of Fame has a small section on moonshine, including one of Johnson’s stills, it downplays moonshine’s role. Pierce says it gives the impression that only a couple outliers were involved. But without the skill of young bootleggers, it’s possible that no one would have seen stockcars as something worth racing and watching. Moonshine was the fuel NASCAR raced on, while pretending it needed only gasoline.

That attitude may be changing. In October 2018, NASCAR joined forces with Tennessee’s Sugarlands Shine to sell an official moonshine. When asked whether it was correct to say NASCAR didn’t always publicize this part of its history, Chief Revenue Officer John Tuck stated by email, “Moonshine has a historic connection to the roots of our sport and that association has always been present with our fans … who embrace the lineage of our sport.”

The connection between NASCAR drivers and moonshine seems more corporate in recent years. In 2007, Johnson cashed in on his legacy by creating Midnight Moon—a “moonshine” made indoors at a legal distillery and sold in clear mason jars at stores. But some men just can’t stay away from the good stuff, the secretly stilled moonshine, white mule, or mountain dew. Just 10 years ago, former NASCAR driver Dean Combs was charged with operating an illegal still. “I’d drink it for a cold,” he told The Richmond-Times Dispatch. He’d made a batch that morning. Authorities confiscated over 200 gallons.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook