The Notorious Oyster Pirates of Chesapeake Bay

They were the colorful villains in a conflict that lasted almost a century.

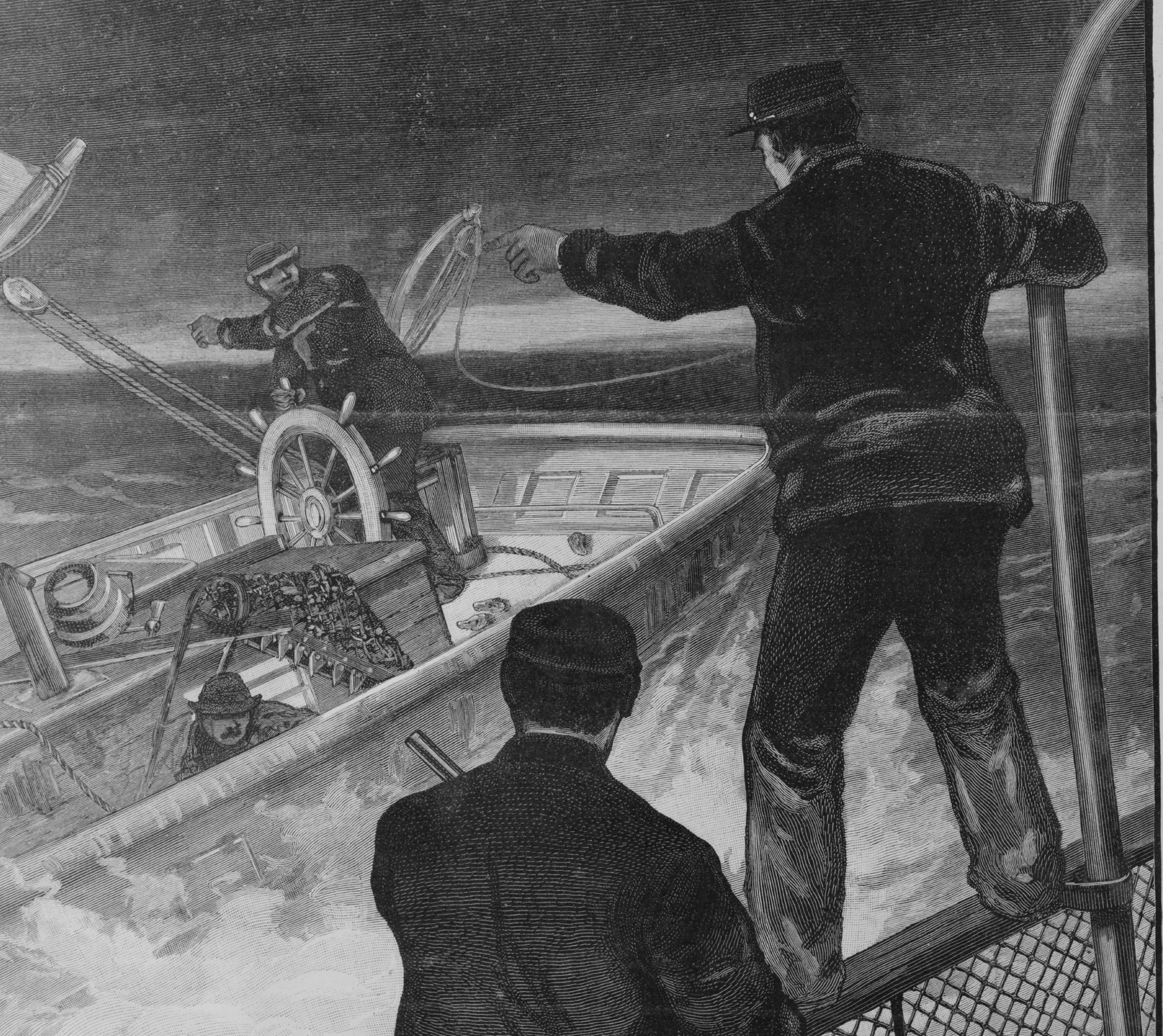

It was dark when Roy Thompson, a 20th-century river worker, came under fire from local oyster police. He and a young man named Frank had snuck onto the waters of the Chesapeake Bay to harvest oysters. As they hauled their load aboard the boat, shots rang and bullets peppered the vessel. Thompson revved his watercraft into action, racing forward in an attempt to outrun the police, who were rapidly approaching, their gunfire shattering his windows. But his boat, chock-full of oysters, was too heavy for a hasty getaway. He ordered Frank to start dumping the mollusks back into the bay to lighten the load, desperate to escape the ambush. Though a bullet did shoot the shovel Frank was using right out of his hand, the two men managed to survive unharmed.

It wasn’t their first, or last, close encounter with the authorities.

Thompson and his fellow nighttime dredgers were among the thousands of oyster pirates who pillaged the Chesapeake Bay area during the Oyster Wars that rocked Maryland and Virginia’s shared waters from the mid-19th century all the way up until the late 1950s. Beneath the dark cloak of the night sky, hidden behind veils of mist and clouds, the pirates plundered the bay as part of a loosely united ramshackle crew, known as the Mosquito Fleet for their small, swift boats.

Unlike the historic pirates of the open ocean, these men weren’t searching for gold coins or sunken jewels. Their treasure came in a shell rather than a chest, its value found within the slimy meat shuttered inside. In fact, calling members of the Mosquito Fleet “pirates” doesn’t quite accurately depict what they truly were: poachers. The shellfish thieves were illegally pilfering a valuable natural resource.

Though oysters were originally considered a poor man’s food, after the Civil War people’s attitudes toward the briny meat began to shift. Northerners with a newfound disposable income began to see oysters as somewhat of a high-class cuisine worthy of their palates. With large portions of the New England oyster stock already depleted, watermen turned toward the abundance of mollusks farther down the Atlantic coast. The waters around Maryland and Virginia boasted some of the richest, most plentiful beds in the world, spurring an oyster boom akin to an aquatic gold rush. Soon, people from across the globe were importing Chesapeake Bay oysters, coveting their own chance to slurp mouthfuls of the mollusk. By 1870, the oysters were at the forefront of a $50 million seafood industry.

For natives of the Chesapeake Bay area, on both the Maryland and Virginia side of the border, aquatic resources—used for food, fertilizer, and as a source of income—were an essential aspect of everyday life. The poorer waterfront communities relied on the oysters to make the money they needed to feed their families. They’d already spent the years prior to the Civil War watching northern fishermen trickle into their waters with advanced equipment used to reap bountiful harvests.

When watermen from New England arrived in the Chesapeake Bay, they brought with them their dredgers. The steel-framed, chain meshed nets were used to scoop the shellfish from their beds. The equipment, which had led to the massive decline of oysters along the country’s northern shores, was far more effective than the rake-like hand tongs traditionally used in the Chesapeake. In an effort to preserve its precious resource, Maryland enacted laws that limited oyster harvesting to state residents, then in 1865, further required that its local oyster harvesters purchase a yearly license. Virginia, however, did not.

This posed a problem.

The Chesapeake Bay falls within the territory of Maryland and Virginia, and while both state governments were aware of the value of the sought-after sea creatures, the odd geopolitical nature of the shared waters made the oyster industry difficult to control. As the Washington Post has noted, per a 1785 agreement, both states had to pass the same legislation in order to enact any laws regarding the shared waters of the Potomac River, which feeds into the Chesapeake Bay. But Maryland and Virginia disagreed with each other over the necessary policies to put in place to regulate the oyster harvests.

This legislative friction reflected the mounting tensions among the citizenry. Locals, who originally relied on tongs, resented the Northern newcomers because their dredges allowed them to collect a heftier bounty. After Chesapeake Bay residents acquired dredgers of their own, they also found themselves fighting against gun-happy local authorities, from both Maryland and Virginia, who were desperately trying to maintain order on the chaotic waters.

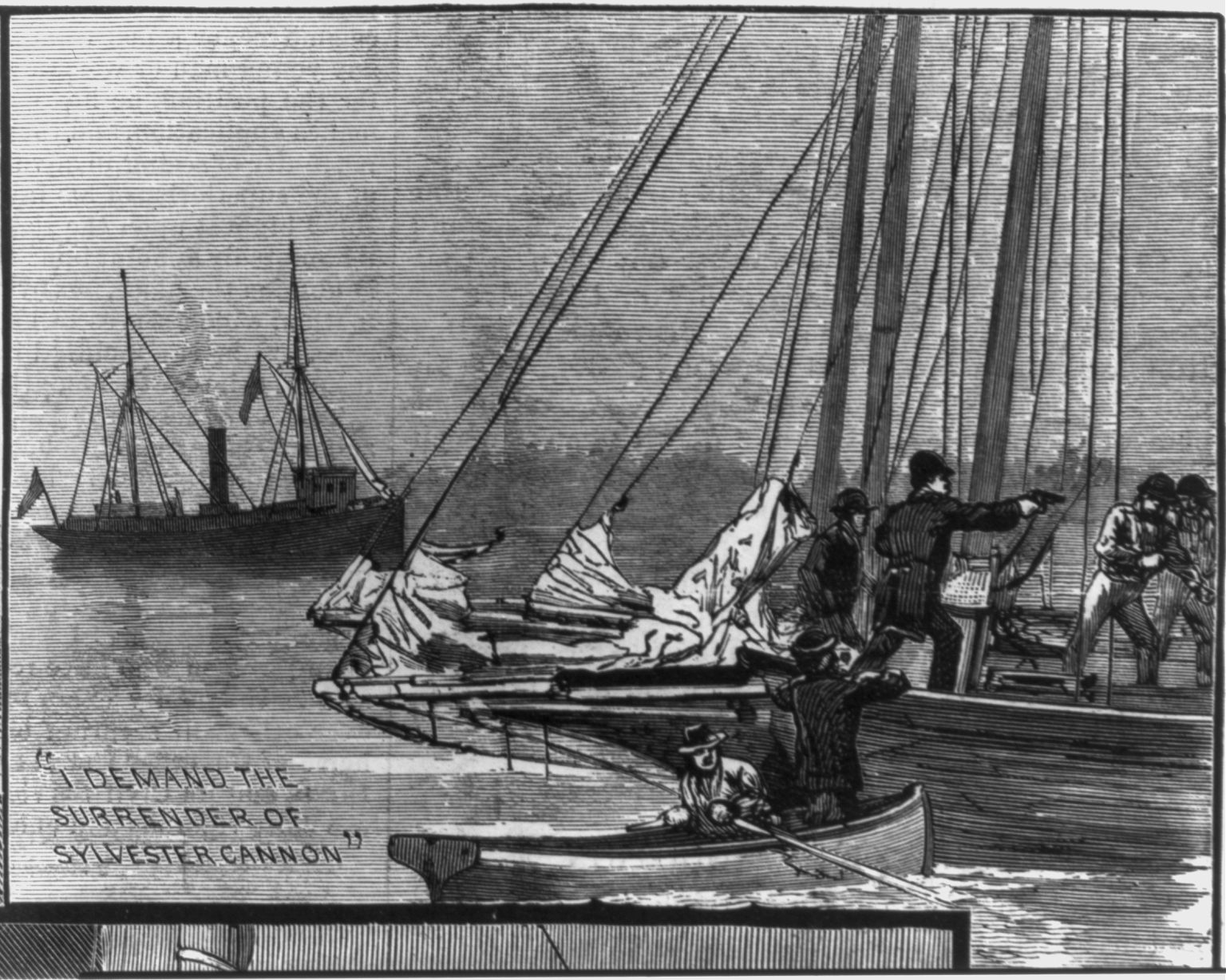

In 1868, Maryland created its own armed Oyster Navy in an effort to regain control of an area that had turned into something of a watery no-man’s land. As James Tice Moore details in Gunfire on the Chesapeake, Virginia, not to be outdone despite its lax laws, eventually began its own crusade to capture illegal harvesters.

But the Oyster Navy was a poorly planned endeavor. The underfunded entity struggled to keep pace with the abundance of pirates. The captains abused and risked the lives of their employees, most of whom were immigrants.

The Mosquito Fleet were a hardy bunch. Many of the original members were veterans of the Civil War. They weren’t an exclusive group, nor did they adhere to racial segregation—the only prerequisite for joining the notorious fleet was the ability to outrun the police. An inspector from the Fish and Wildlife Service, quoted in 1887, called the pirates, “unscrupulous men, who regard neither the laws of God nor man.” According to him, they were the lowest of the low, hailing from disgraceful places such as jails and the “vilest dens of the city.”

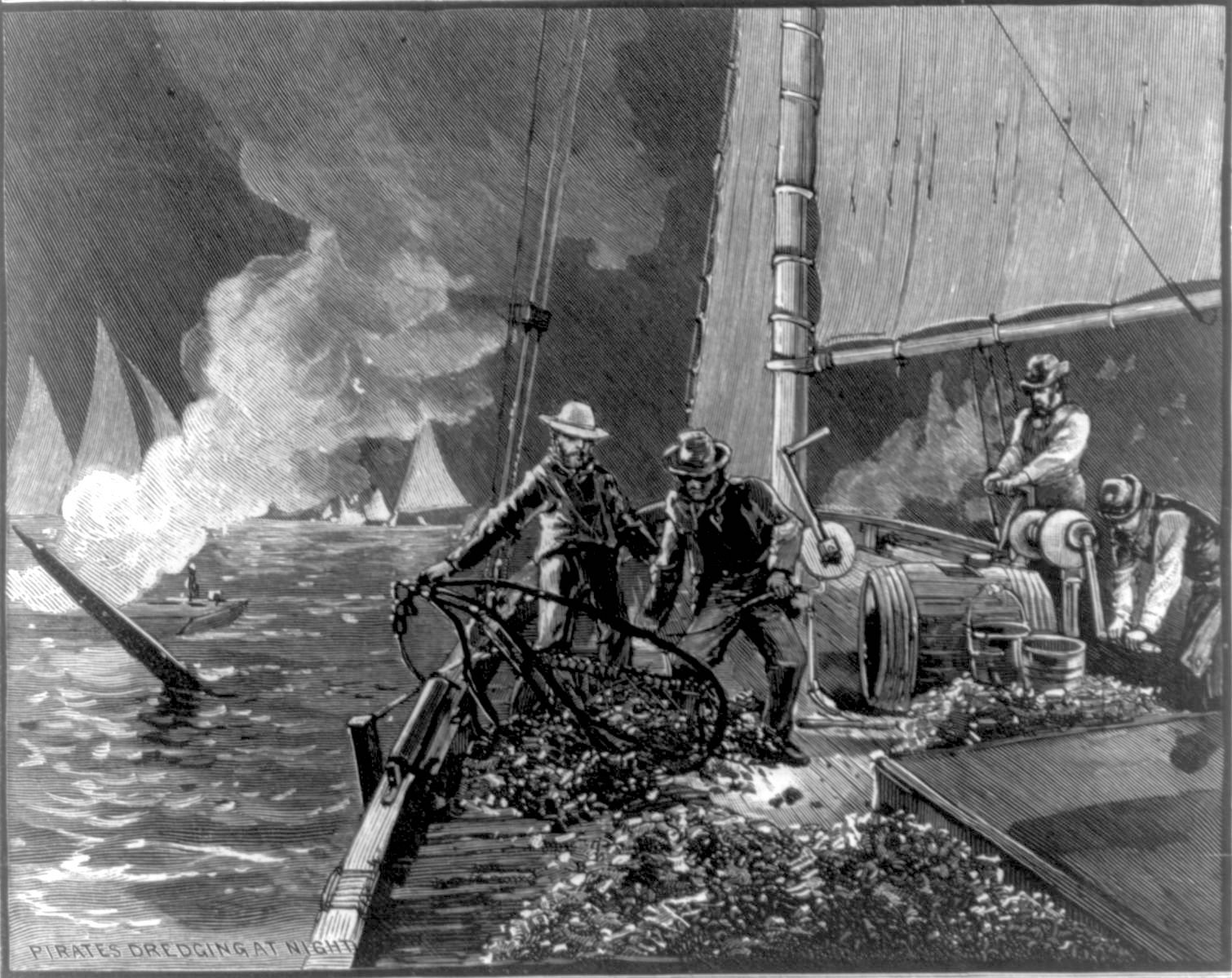

Many of the men were locals who had grown up earning their livelihoods from the water. For them, the oyster boom was a welcome opportunity for economic growth, a chance to take advantage of a surplus resource. “Oysters was ass-deep in the Potomac River,” remembers Walter Dorsey, a native, in an oral history captured by the journal SlackWater. As John Wennersten describes in The Oyster Wars of Chesapeake Bay, the pirates took to conducting nighttime raids within the water, slinking throughout the bay to illegally dredge oysters. After Maryland outlawed dredging in the early 1930s, Virginia residents, claiming they were adhering to their own state laws (or lack thereof) continued anyway. “They figured that the good Lord put the oysters out there for them and to hell with anybody else,” said Earl Brannock, a retired oyster police officer, in SlackWater.

The Mosquito Fleet braved treacherous nighttime conditions all the way through the middle of the 20th century. They not only faced poor visibility and sometimes unpredictable waters, but also police forces lurking within the coves. Police boats would often dim their lights, sitting and waiting in utter blackness until it was time to stage an attack. Then, they’d rush forward, firing their guns at the unsuspecting poachers, sometimes even ramming their boats into the offending vessels of the Mosquito Fleet. Of course, the pirates typically fired right back.

However, the oyster police did eventually take matters too far. On the night of April 7, 1959, Berkeley Muse, a man from the rugged gambling haven of Colonial Beach, decided to tag along with his buddies Harvey King and John Griffith for a bit of midnight dredging. The three set out on their covert mission, unaware of a nearby police stakeout. When police opened fire on the small band of pirates, King took a bullet to the leg. Muse, who had decided to join King and Griffith for a bit of mischief, was shot and killed.

Muse’s death prompted the Maryland and Virginia governments to finally attempt to work together to put an end to the backwater madness. After a long period of turbulent negotiations, the two states came together to support the Potomac River Fisheries Commission bill, which dictated how to conserve and manage their shared maritime resources. Congress approved the plan in October of 1962, and President John F. Kennedy signed the bill into law on December 5, effectively ending the Oyster Wars that for nearly 100 years had ravaged the Chesapeake Bay.

*Correction: This article has been updated to correct an erroneous reference to oysters as crustaceans.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook