How Tainted Treats Led to a Halloween Tragedy in 1858

A poisoned batch of peppermints devastated an English town.

On October 30, 1858, William Hardaker set up his sweets stall at Green Market in Bradford, England. That afternoon, factory workers lined up to spend their payday wages on his zebra-striped humbugs, a type of hard candy often flavored with peppermint. Hardaker enticed customers with knock-down prices: a discount, to make up for the slight discoloration in the day’s batch. By the time the market shut, Hardaker had sold five pounds of sweets. And by the next morning, two local children, aged eight and 11, were dead.

This was a time when child mortality was high and cholera ran rampant, leading the police to initially put their deaths down to natural causes. However, by the evening of October 31, the Bradford Observer reported that “sudden deaths were rapidly multiplying on every side.”

Police arrived to one harrowing scene at #30 Jowett Street. Two brothers, aged two and five, lay dead within the home. Their distraught father, Mark Burran, suggested the peppermint lozenges he’d bought could be behind their deaths. His suspicion was confirmed when a young man in the house insisted on testing the candies himself, ate two, and promptly fell ill.

Burran told the police that the candy stall was in the Green Market, and that the seller went by the moniker “Humbug Billy.” Meanwhile, doctors across Bradford scrambled to help scores of sick and dying people.

In Victorian England, it wouldn’t have required a giant leap of imagination to suspect poisoning. “Lots of things were poisonous,” says Laura Sellers, curator at Thackray Medical Museum in Leeds. At the time, it wasn’t uncommon for arsenic to be present in wallpaper, dress fabric, and even sprinkled about as a household cleaner. “Poison was also considered the murderer’s weapon of choice,” adds Sellers.

Just a year before the Bradford deaths, Madeleine Smith, a young woman in Glasgow, had been charged with murdering her lover with arsenic. Smith was acquitted but the trial was a media sensation. Arsenic was easy to buy, tasteless, and odorless, and its effects after ingestion could often be attributed to illness. That is, if the amount of arsenic ingested was moderate, and not the horrifyingly large amount later discovered inside Hardaker’s humbugs.

If the police believed Hardaker to be a murderous mastermind, though, they were soon disabused. Instead, they discovered him at home, writhing in agony, having helped himself to one of the humbugs the night before. The true culprit behind the Bradford humbug poisoning was, in some ways, worse than a lone-wolf villain: People across Bradford were dying because of systematic carelessness and a pursuit of profit.

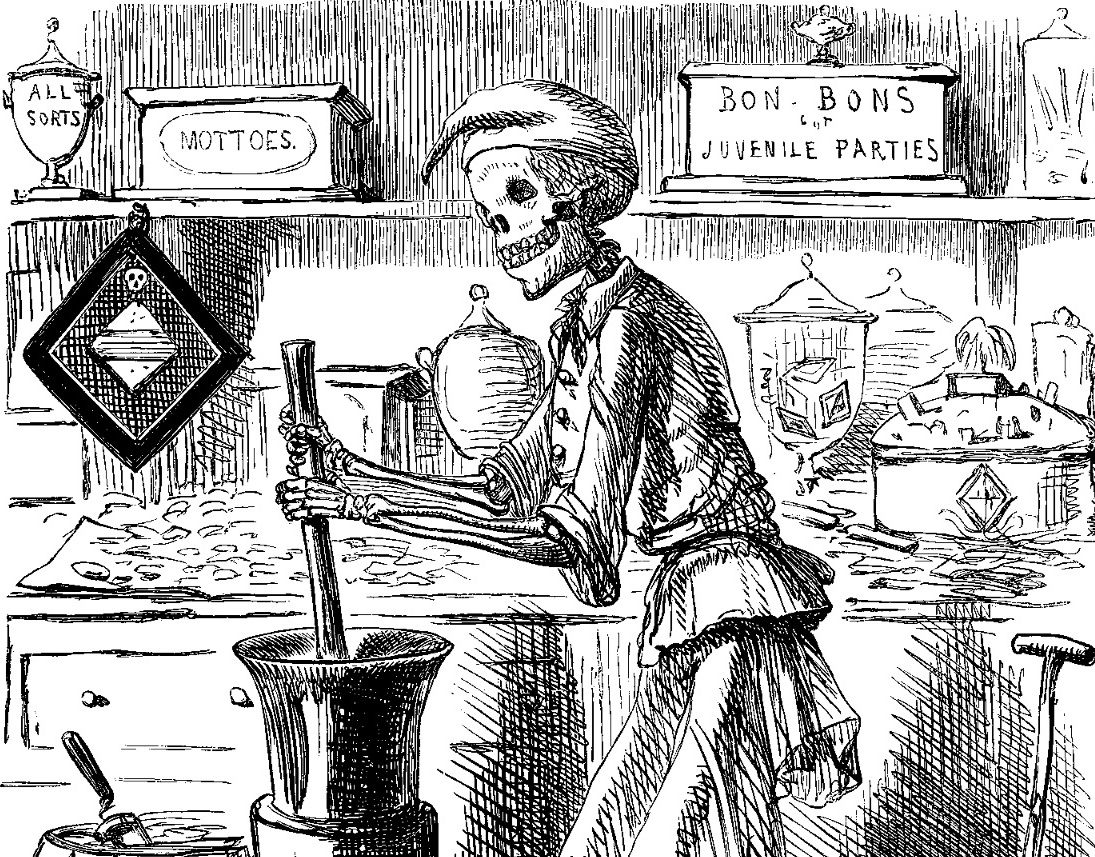

The ill stallholder first pointed the finger at Joseph Neal, the confectionery wholesaler who had sold him the lethal lozenges. Neal’s candy recipe included a mix of sugar, gum, water, peppermint oil, and daft. “Daft was a sort of gypsum powder,” says Sellers, “put into products to replace some of the sugar and reduce the cost of production.” Adding bulking agents to food was common and legal at the time. Sweets, though, were particularly prone to adulteration due to the high cost of sugar.

Around two weeks before the tragedy, Neal had sent an employee to buy 12 pounds of daft from a druggist in nearby Shipley. On arriving, Neal’s assistant discovered that the druggist, Charles Hodgson, was ill in bed. The shop was instead staffed by an inexperienced apprentice, William Goddard, and Hodgson was hesitant to let him take the order.

Neal’s employee, though, was unwilling to leave empty-handed. Reluctantly, Hodgson instructed Goddard where to find the daft, directing him to a large container in the corner of the shop. Goddard dutifully scooped out large quantities of white powder from an unlabeled container to give to Neal’s assistant. But he had chosen the wrong corner. Instead of daft, Goddard handed Neal’s assistant 12 pounds of arsenic trioxide.

In turn, the assistant took the hefty package of arsenic to James Appleton, a sweet maker also employed by Neal. Appleton added all 12 pounds to 40 pounds of lozenge mixture. Later, after he finished the candies, Appleton began vomiting, likely from exposure to the enormous amount of arsenic. At the time, he merely presumed he’d caught a stomach bug. A court later heard how each candy contained enough poison to kill a grown man.

Officers and bell ringers then spent what was left of All Hallows’ Eve rushing around the district trying to warn as many people as possible about the danger. As the Bradford Observer reported, “the quiet slumbers of innumerable persons were broken at midnight by the warning … the walls of the town were thickly covered with an official precaution from the chief constable.” The alert likely saved countless lives. However, it came too late for the seven adults and 13 children that died and for the hundreds who were seriously ill. The youngest child to die was just 17 months old.

After tracing how the arsenic ended up in the humbugs, the police decided it should be poor Goddard, with his three weeks of pharmacy experience, who should be arrested for the deaths. In the end, Goddard, his employer Hodgson, and Neal the candy wholesaler were all charged with manslaughter. Shockingly, the three men were acquitted that December, with the prosecution unable to prove any existing law had been broken. Hardaker returned to selling confectionery in Green Market, after recovering from his own consumption of one of the sweets.

The case, though, lingered in the public’s imagination. Sellers says the high-profile poisonings contributed to the passing of the landmark Pharmacy Act of 1868. The act ensured that named poisons could only be sold in special bottles made from colored, textured glass, to provide a strong visual cue to the contents. Specific poisons also had to be labeled, and shops had to keep registers noting down the names of the buyers.

Yet even with new laws, it was still legal to buy arsenic for household use. According to Kitty Ross, a social history curator at Leeds Museums and Galleries, a huge number of consumer products containing toxins continued to be sold. In accordance with the Pharmacy Act, they were labeled as poisonous, but were then marketed to consumers as harmless.

Additionally, candies ended up causing extreme bodily harm well into the 20th century. For an exhibition at Abbey House Museum in Leeds, Ross once came across a jar for throat lozenges containing potassium chlorate, a toxic and highly combustible substance. “It’s the same material that’s in blasting caps,” says Ross. In August 1955, nearly a century after the Bradford poisonings, a dry cleaner in Sunderland died when a customer left such throat lozenges in their coat pocket. Once in contact with cleaning spirits, the sweets exploded.

While poisonous and explosive candies seem like shocking scandals confined to another era, food and pharmaceutical contamination scandals persist today. Too often, such tragedies result from carelessness, cost-cutting, and lack of regulation, all of which contributed to the Bradford humbug poisoning of 1858. “People tend to think, ‘Look at those stupid Victorians,’” says Ross. “But many of the same issues keep on coming back around.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook