Remembering the Clandestine ‘Aunty Bars’ of Prohibition-Era Bombay

Grabbing a drink once meant moonshine in a neighbor’s living room.

When Roland Francis’s father didn’t come home on time, he knew something was wrong. It was 1962 when the Bombay-born 13-year-old set out in search of his dad. He ran into a friend, who told him that a cordon of officers had formed around one of the neighborhood buildings. Though he wasn’t old enough to drink, Francis was old enough to understand what this meant during the city’s prohibition era. The police had busted one of the neighborhood bars, and his father must have been caught up in it.

Moments later, Francis recalls, his father, accompanied by another man, coolly strode towards him. He had lucked out—his drinking buddy had been an officer.

“When they found out that this guy was from the police, they let him and my father off,” Francis recalls. “They told him to just disappear fast before they arrested the other guys.”

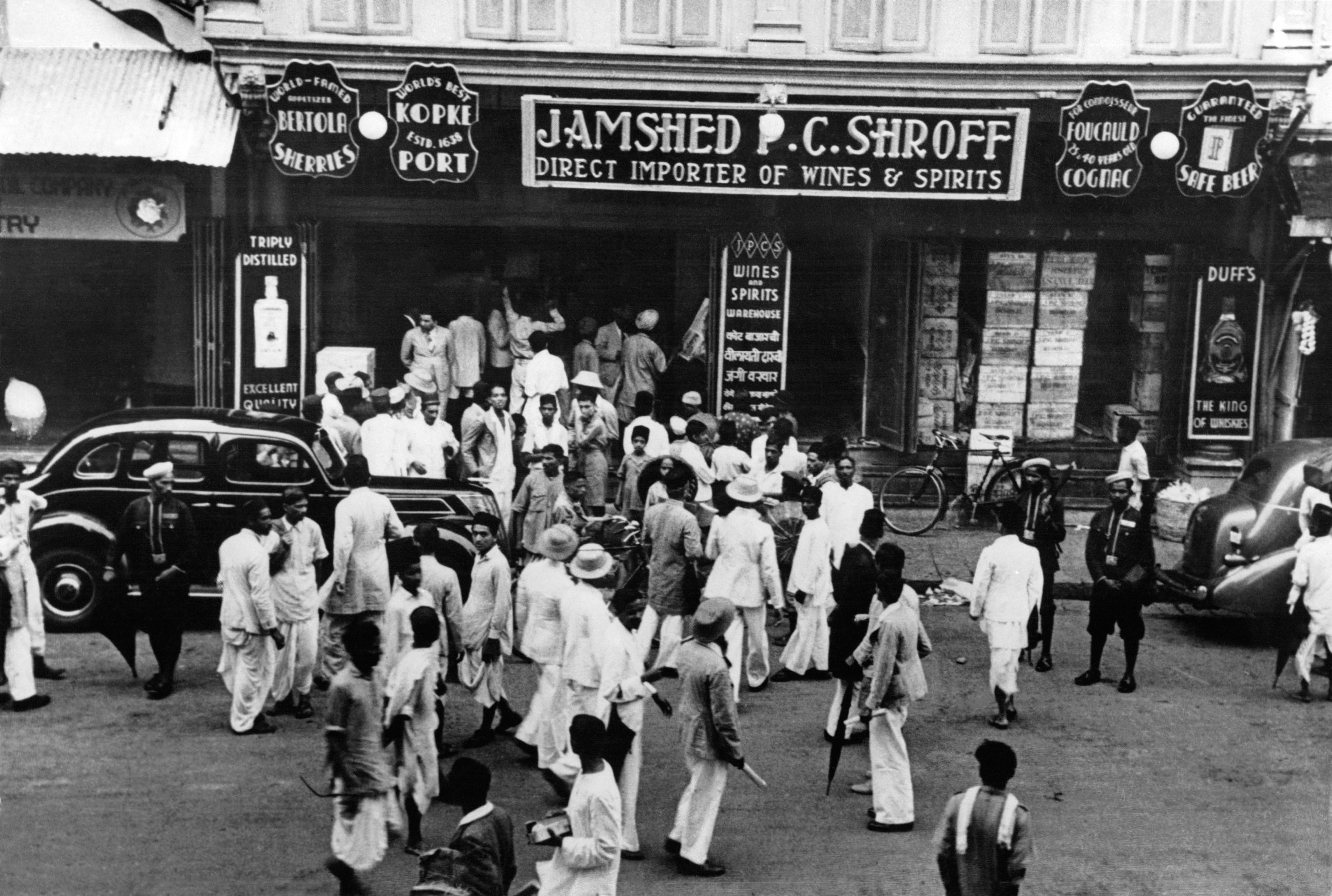

In prohibition-era Bombay (now known as Mumbai), police raids could be bad news for drinkers. But, for the most part, few were deterred. In fact, raids became commonplace, a sometimes terrifying, sometimes comical element of city lore surrounding the illicit alcohol industry of the ‘50s and ‘60s. Even police officers found ways to imbibe.

“Everybody’s daddy and uncle had a wild story about almost being caught by the police or shimmying down a drainpipe,” says Naresh Fernandes, editor of the digital publication, Scroll.in.

Prohibition often gives rise to its own memories, nostalgia, and mythology—and Bombay was no different. However, it seems some of these stories are at risk of being forgotten by younger generations. Much of the prohibition nostalgia that younger Mumbaikars harbor, Fernandes notes, is for something else entirely. “The wonderful irony is that every now and then, some kid will set up a prohibition-era themed bar, but the prohibition it’s modeled after is always Chicago!”

While there would be organized crime, large bars, and a bit of glamour during Bombay’s prohibition era, that would all come later. Before the city’s illicit liquor trade became a booming business, there was another, much smaller, operation at play. And it could be found in the humble, single-room apartment of a middle-aged aunty.

The aunty bar itself was nothing to raise a glass to. At a glance, it was a small, grimy room where thirsty men furtively guzzled rotgut and moonshine behind dirty curtains. But behind those curtains, too, were highly resourceful women who did whatever it took to provide for their families.

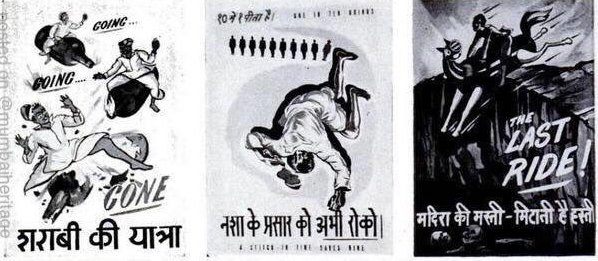

In India, prohibition began with the Independence Movement. Mahatma Gandhi considered liquor a “serious defect,” and believed drinking was an obstacle in gaining control over one’s self and one’s country. “Nothing but ruin stares a nation in the face that is a prey to the drink habit,” he once said. “History records that empires have been destroyed through that habit.”

After India gained independence, the Bombay Prohibition Act of 1949 was put into place, banning the sale and consumption of all liquor—from whisky to cough syrup. The following year, a “directive principle” written into India’s constitution declared nationwide prohibition, but left it up to each state to determine whether or not to implement the dry laws. The state of Bombay enacted the laws to the fullest extent. But, as is often the case with prohibition, even the law couldn’t separate citizens from their spirits.

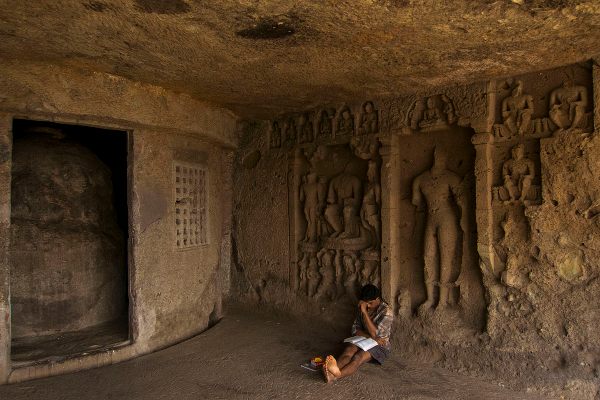

To the south of Mumbai lies Goa, a state on India’s western coast that was colonized in the 16th century by the Portuguese, who brought with them cashew trees and Catholicism. After nearly three centuries of converting Hindus, Muslims, and Jews to Christianity, often forcefully, both cashew trees and Catholic customs took root. Goans began crafting kaju feni, a potent spirit made from distilling the red, bulbous fruit of the cashew tree. Many adopted Portuguese surnames, began eating pork and beef, and incorporated feni into their lives—often as a part of Catholic feasts, rituals, and celebrations. In the late 19th century, many Goans migrated to Bombay in search of employment, bringing with them feni and religious beliefs that embraced drinking.

Prohibition presented both an obstacle and an opportunity for those with a taste for liquor. At the end of the day, men of all classes and creeds wanted a drink. And so it was mostly middle-aged Goan Christian women, often widowed or with unemployed husbands, who met the demand. Relative to most Muslim and Hindu women, they held relaxed views on alcohol—and most importantly, they needed to feed their families.

In the early days of prohibition, the aunties typically sold feni or moonshine, which was often concocted from a somewhat random assortment of old, fermented fruits. According to Bombay-based journalist Sidharth Bhatia, the liquor could be made at home or “brought in large bottles, containers, and even rubber tubes from other distant distilleries in remote parts of town, slums, where police presence was minimal.”

Transporting the liquor required a bit creativity. To keep police officers at bay, individuals affected by Hansen’s Disease (what was then referred to as Leprosy) often transferred moonshine from the distilleries to the aunties’ homes. In other cases, rubber bicycle tires, tubes, or hot water bottles filled with moonshine might be stuffed under a woman’s garments, creating an unassuming bulge that could be mistaken for a baby.

The joints themselves, however, required no such disguise. Run out of the women’s homes, they were indistinguishable from surrounding apartments—unless you knew where to look. At first they tended to cluster in Goan and Catholic neighborhoods, such as Dhobi Talao and Bandra, but soon, they could be found across the city. The only surefire way to track one down was through word of mouth. Aside from being in the know, there were very few ways to identify a joint.

But, according to one former patron, there was one subtle yet reliable sign that an aunty bar was near: boiled eggs. A vendor selling boiled eggs, often alongside another roasting kaleji, or fried liver, served as a sort of directory to your local joint. When asked, these street vendors could direct patrons to the nearest aunty, perhaps in the hope that departing drinkers might swing by for a convenient nighttime snack on their way out.

According to Francis, visiting an aunty bar felt less like going to a bar and more like stopping by a neighbor’s house. “These aunties’ joints were really a part of their homes,” he says.

Patrons were expected to treat the bar like someone’s home, too. “Respect was paramount,” says Bhatia. “No drunken behaviour, no tomfoolery—drink quietly or get thrown out.”

A typical “bar” often consisted of a single room, where you could find a table, a few chairs, and perhaps even a bed, which might provide cozy overflow seating. “Their homes were no more than, say, 500 square feet,” says Francis, “and about half of that room would be reserved as a sitting place.” Whenever a customer walked in, the home became the aunty bar, and the aunty bar, for some, became a home—or at least a space with which customers became intimately familiar. Loyalties ran deep, as the aunty in charge would offer a full cup and, at least in legend, a pair of eager ears. “That was part of the mythology,” says Fernandes. “She would listen to your stories and get to know your sordid life.”

Aunty-bar hopping certainly wasn’t standard, and some men continued to frequent their local aunty even once legal bars and clubs opened up. And this cut both ways—aunties could be fiercely loyal to their patrons. According to Francis, the women sometimes bailed out jailed customers following a raid. “They didn’t want to stop them from coming to their places the following day.”

The late journalist and satirist Behram Contractor, under the pseudonym Busybee, has written in his column, Round and About, on the forced intimacy that arose from such close proximity between families and patrons. In one post, he describes in detail one of his favorite drinking spots: The second-floor apartment of an elderly woman and her unemployed husband.

“I suppose … prohibition was a great boon to them,” he writes. “Without illicit liquor to sell, they would have had no livelihood and would have died of starvation. At least that was the rationale of my drinking there.” When the daughter of the elderly couple passed away, Contractor dropped by to pay his respects. “She was lying in the bed, candles all round her. In the opposite corner of the room, customers were sitting and drinking.”

As more and more aunties transformed their living rooms into bars, patrons from all walks of life trickled into their local aunty’s bar. According to Bhatia, customers ranged from “middle class professionals” to “down and outers” to journalists—and lots of them. College students, too, snuck in to gulp down a half bottle of feni before a night out—some, admittedly, equally nervous to run into their fathers as to get caught in a raid.

All customers did have one thing in common, however: They were all men, some of them well-educated and from well-to-do families. Several enterprising aunties saw this as an opportunity to become both bartender and matchmaker at once. According to Francis, some of these pairings did, in fact, lead to marriages. “It became a meeting place,” he says. “But nothing untoward or sexual happened there.”

There likely wouldn’t have been time for it. With limited space and the ever-present risk of raids, most customers stayed at the joint for an hour or less. “It was not a relaxed watering hole,” says Bhatia. “People wanted to drink and get out.”

Raids were a threat to customers and aunties alike—but more often than not, policemen preferred the bars to stay open. According to several people living in Bombay at the time, there was a kind of informal agreement that allowed both to coexist. Each Monday, the police came around to demand their “hafta,” a weekly cut of the aunties’ earnings. This system typically worked for both parties, but when an argument arose, it wasn’t uncommon to see an aunty chase the officer straight out of her home.

The women who ran these bars were tough, because, as the family’s breadwinners, they had to be. They not only took on antagonistic police officers and kept customers under control, but also persisted despite public disdain. While most showed the aunties respect behind closed doors, the profession was widely frowned upon outside of the establishments.

Nevertheless, the women bold enough to sell the brew saw a payoff. At its peak, the aunty bar was a successful venture that, in the end, allowed for vast economic mobility among families that had started out relatively poor in Bombay. According to Francis, many of the aunties’ children were able to go to school and become doctors or lawyers. It was, perhaps, a risky business, but it was the aunties’ way of giving their children a better life.

Once people realized how lucrative the business was, it spread beyond Catholic aunties. Gangs and bootlegging businessmen entered the underground trade, building larger, more professional venues. Many believe that profits from these larger operations gave rise to the “underworld” of Bombay—often associated with gambling, sex work, and even the infamous mob boss Vardarajan Mudaliar.

In the mid 1960s, prohibition laws were relaxed, due to increasing difficulty in implementation, along with mounting pressure from the state’s sugarcane lobby, which saw potential profits in legalizing liquor. By 1972, prohibition had been abolished. In its place, a permit system was erected, requiring all drinkers—those who need liquor for the “preservation or maintenance of health”—to possess a license. Unbeknownst to many first-time visitors to Mumbai, the permit system still stands today. Though not commonly enforced, there have been several recent cases of officers raiding popular nightclubs and arresting unsuspecting imbibers.

Bootlegging, too, persists in Mumbai—bringing cheap, unregulated booze into the city for those who can’t afford licensed liquor. It’s not uncommon for a particularly bad batch, spiked with pesticides for potency, to kill dozens of people, disproportionately those who are impoverished.

But the aunty bar, a widespread relic of early prohibition-era Bombay, seems to have vanished as quickly as it arrived. The bustling nightlife of modern-day Mumbai bears no resemblance to the rushed visits to cramped apartments in the ‘50s and ‘60s. For better or for worse, the remaining residues of the neighborhood joint seem to exist mainly in the collective memories of former patrons and their relatives, some of whom still have a misty-eyed fondness for their local aunties’ bars. Others, however, don’t seem to mind its disappearance.

“There’s nothing romantic about drinking rotgut in a smelly tenement,” says Fernandes, “though everyone would like to believe there was!”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook