In England, the Right to Daylight Can Be a Legal Matter

And they have the “Ancient Lights” signs to prove it.

Perhaps you’ve heard the term “spite house,” or a building erected on a small slice of land after a dispute between neighbors. These inconvenient, often scarcely usable homes are explicitly designed for revenge, sometimes by blocking a hated neighbor’s view. Infamous examples include the 10-foot-wide Alameda Spite House and the sliver-thin house in Beirut, Lebanon, known only as “The Grudge.” Fortunately for some property owners in England, no window-blocking buildings should be built any time soon, thanks to a property law that’s been around, in some form, since 1663.

The “Right to Light” is a stipulation that falls under the Ancient Lights law, which gives long-standing property owners the right to receive adequate and unobstructed daylight through their building’s windows. A person was historically entitled to this if natural light and air had passed freely through their windows for a certain amount of time. In a British law dictionary written by John Bouvier in 1856, he described the Ancient Lights law as applying to “windows which have been opened for twenty years or more, and enjoyed without molestation by the owner of the house.” If a neighbor attempted to infringe upon this by building a structure or planting trees, the owner had the power to sue them for “nuisance” and walk away with a check (and, ideally, a restored view).

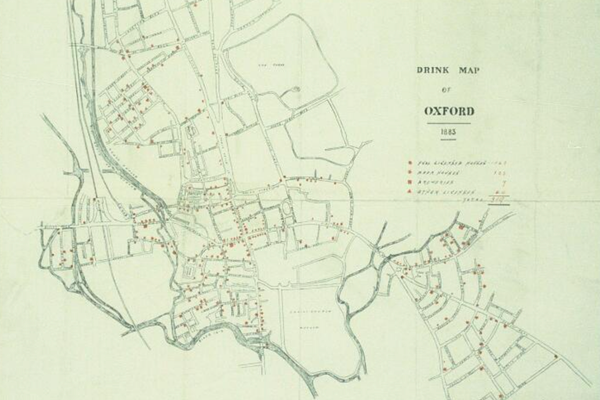

This law led to the careful placement of “Ancient Lights” signs under windows that were protected by the ordinance. And today these signs are still found on buildings around London and other English counties, such as Dorset and Kent. Curious explorers have even created a map of where these antiques are located; popular ones include those underneath the back windows of homes on Albemarle Way, a seemingly misplaced one in a dead-end alleyway in London’s Chinatown, and a large, boldly printed sign in Newman Passage.

How much natural light is a person entitled to? Well, that’s where this law gets a little … shady. A building owner’s windows don’t even have to be completely blocked by a neighboring obstruction for the “Right to Light” to be invoked. It simply insists that the same level of illumination the owner has experienced for twenty years must be maintained, which is decidedly vague. A famous 1904 legal case, Colls v. Home & Colonial Stores Ltd, determined that Colls, the owner of a nearby building, was entitled to “sufficient light according to the ordinary notions of mankind” (yeah, that’s clearer) after he argued that his ground floor office would suffer from the loss of sunlight if the store was built. Colls won the case thanks to the “expert witnesses” the court deferred to.

Percy Waldram, one of these Ancient Lights experts, proposed a method in the 1920s that would, ideally, standardize the sufficient amount of light people could claim. He suggested that “ordinary people” required one foot-candle (a measure of light intensity) for reading and other work. While this quasi-arbitrary method is still in use today, it’s met with skepticism.

Though this 17th-century urban planning law has been through changes since it was first inked (the language England uses today is based more closely on the Prescription Act of 1832), the power that property owners have to demand ample daylight is still a relevant debate. The Ancient Lights doctrine hasn’t caught on in the United States, since restricting building construction threatens new commercial and residential development projects, thus limiting urban growth—at the cost, perhaps, of some daylight.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook