The Forgotten Cookbooks That Fueled Women’s Suffrage

From “pie for a doubting husband” to “spaghetti a la suffragette,” these recipes came with a side of activism.

Alice B. Stockham was a doctor, activist, and champion of causes ranging from women’s suffrage and abandoning corsets to the merits of female masturbation. To those who found her thoughts on women’s rights, comfort, and pleasure difficult to digest, Stockham offered palatable chasers in the form of recipes for custard-filled cake, graham muffins, and rhubarb toast.

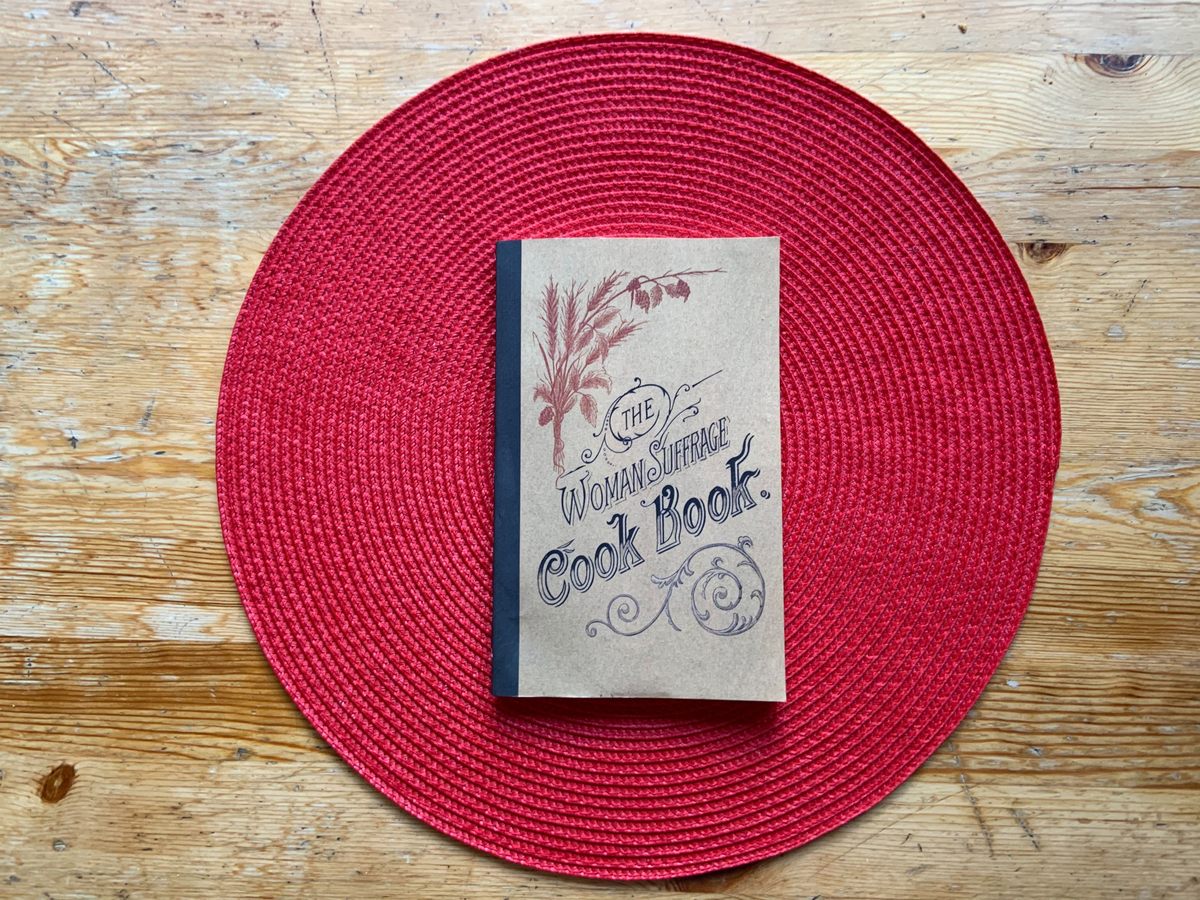

Stockham’s recipes appear in The Woman’s Suffrage Cookbook, compiled by Hattie Burr and published in 1886. Blending recipes with activism, the culinary guide was an early entry in what became a larger trend of suffrage cookbooks. These themed recipe collections proliferated in the United States between the 1880s and 1920, when the 19th Amendment, which stipulated that no citizen could be denied the right to vote on the basis of sex, was ratified.

Published primarily by women’s associations, the cookbooks featured contributions from local members as well as leading figures in the suffrage movement. Carrie Chapman Catt, president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, offered a recipe for pain d’oeufs. Charlotte Perkins Gilman, author of the famous short story “The Yellow Wallpaper,” showed how to make “synthetic quince” using juice from stewed rhubarb. And Lucy Stone, a suffragist and abolitionist who refused to take her husband’s last name, contributed instructions for homemade yeast. To drive the message home, recipes in cookbooks, pamphlets, and suffragist newspapers often had themed names, such as “Spaghetti a la Suffragette,” “Aunt Susan Marble Cake,” or “Suffragette Savories.”

It might seem odd for women who were fighting to be seen as more than wives and mothers to reinforce such traditional roles. But the cookbooks were part of a calculated strategy: By leaning on gendered norms, suffragists were attempting to counter claims that they would abandon their homes and families if they entered the political sphere.

“It was very much intentional on the suffragists’ part,” says Jessica Derleth, a historian who explores this topic in her article “Kneading Politics: Cookery and the American Woman Suffrage Movement” in the Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. “Those gendered issues were confining, but they also gave women real power. It meant that they mattered when they were cooks. It mattered when they fed their children and their husbands. As much as they saw this as a place where they could be attacked, it was also a place where they could defend themselves: ‘I am still a woman. I do still cook and I want to raise good citizens, but I’m also a good citizen. And I can handle the weight of voting and this active form of political participation without losing this part of who I am.’”

With cookbooks, suffragists also demonstrated how women’s gendered experience with tasks such as cooking and childcare made them uniquely qualified to vote on particular civic matters. “It was brilliant in so many ways because they were tapping into all of these other movements around food that were a lot more acceptable than suffrage: home economics, municipal housekeeping, pure food,” Derleth says.

Following the industrialization of food processing and agriculture, issues of food safety and regulation became immensely important—even more so after Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle revealed horrific conditions within the meat-packing industry. “By linking themselves to those issues that were on the forefront of people’s minds, but were more acceptable, it made suffrage more acceptable,” Derleth says.

L.O. Kleber’s The Suffrage Cook Book of 1915 features a satiric recipe that mentions a few civic issues that women pledged to fix with the vote. In the entry “Pie for a Suffragist’s Doubting Husband,” there’s an “ingredients list” of “8 reasons,” including “poisonous water,” “impure food,” and “child labor.”

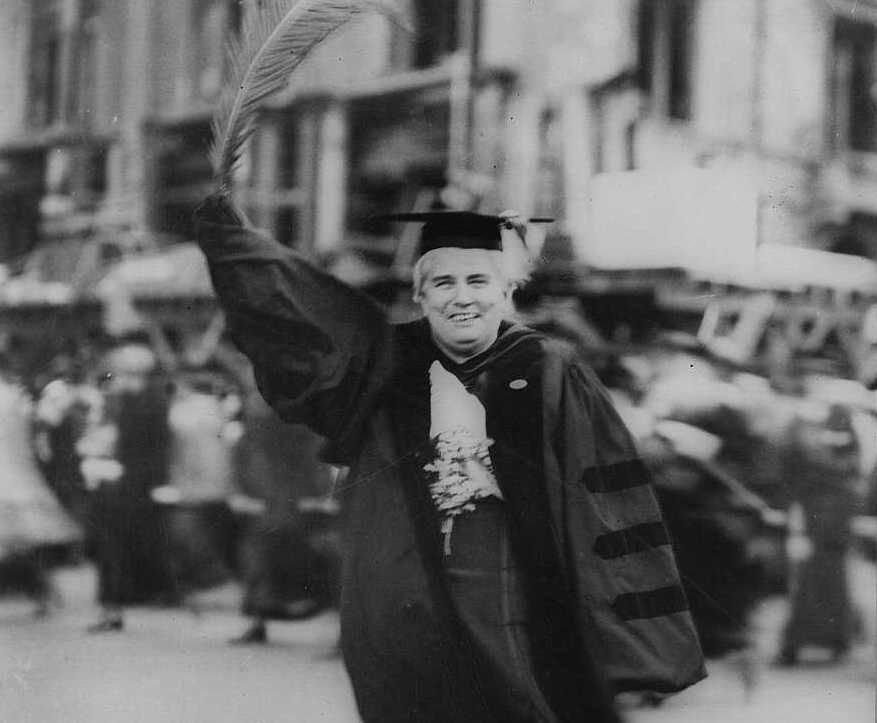

While the cookbooks helped craft a more “acceptable” image for suffragists, plenty of activists refused to play the role of happy housewife. Anna Howard Shaw was a physician, minister, and leader in the National American Woman Suffrage Association. Though her sexuality was never explicitly defined, she was unmarried and lived openly with her companion, Lucy Anthony (niece of Susan), for decades. Shaw offers what’s easily the most hardcore recipe in The Suffrage Cook Book (or, perhaps, any cookbook): “I have sent but one recipe to a cook book, and that was a direction for driving a nail, as it has always been declared that women do not know how to drive nails.” For women who might work up an appetite hammering, Shaw does provide instructions for making a bacon-and-cheese sandwich. Lest anyone think she ever made the meal, however, she adds, “I never did it, but somebody must be able to do it who could do it well.”

But Shaw’s nonconforming contribution is a rarity in suffrage cookbooks, which—like the movement itself—made compromises when it came to inclusion and equality to depict an “acceptable” form of suffrage that would appeal to a wider audience. For example, while the recipes bolstered support for women’s suffrage, this largely meant white women’s suffrage. Although there were Black suffragist groups and such leading figures as Ida B. Wells and Mary Church Terrell, these women were in large part excluded from mainstream suffrage organizations.

“The racial and economic status of these women is very evident,” Derleth says. “One cookbook from New York calls for chafing dishes and coffee percolators and devices that could only be owned by middle- and upper-class women.” According to Derleth, this exclusion continued in suffragist cookbooks published during World War I. Due to wheat and dairy shortages, many recipes substituted Southern kitchen staples such as hominy and pork fat.

“You see these ‘traditional Southern’ recipes that are coming from white suffragists and you don’t see any acknowledgement of the role Black women played in Southern cuisine and, the generation prior, that enslaved women played,” she says.

When Tennessee became the 36th state to approve the 19th Amendment on August 18, 1920, the legislation achieved the final step for complete ratification across the United States. But the fight for voting rights was far from over. The 19th Amendment didn’t guarantee that women could easily vote, but simply that no state could deny them that right based on their sex. Anyone looking to suppress voters still had plenty of methods for doing so. It would be 45 more years until the Voting Rights Act of 1965 further protected Black Americans from unfair tactics such as poll taxes or literacy tests.

Even today, BIPOC communities still face voter suppression. Female politicians still face pressure to conform to gender stereotypes or risk being labeled “cold” or “nasty.” But the events leading up to August 18, 1920, show that progress is possible. For those looking to celebrate this complex milestone in voting history, try the below suffragist-themed cake recipes from the early 1900s. Raise a slice to those who made history in 1920 and in 1965, and those who continue to fight for equal voting rights.

Aunt Susan Marble Cake

Adapted from Karo Syrup’s 1913 “For Better Baking” pamphlet

As the suffrage movement gained momentum and companies took note of women’s buying power, an array of suffrage-themed products appeared, ranging from coffee to ovens to cigarettes. Among these promotions were recipe pamphlets devised by food companies.

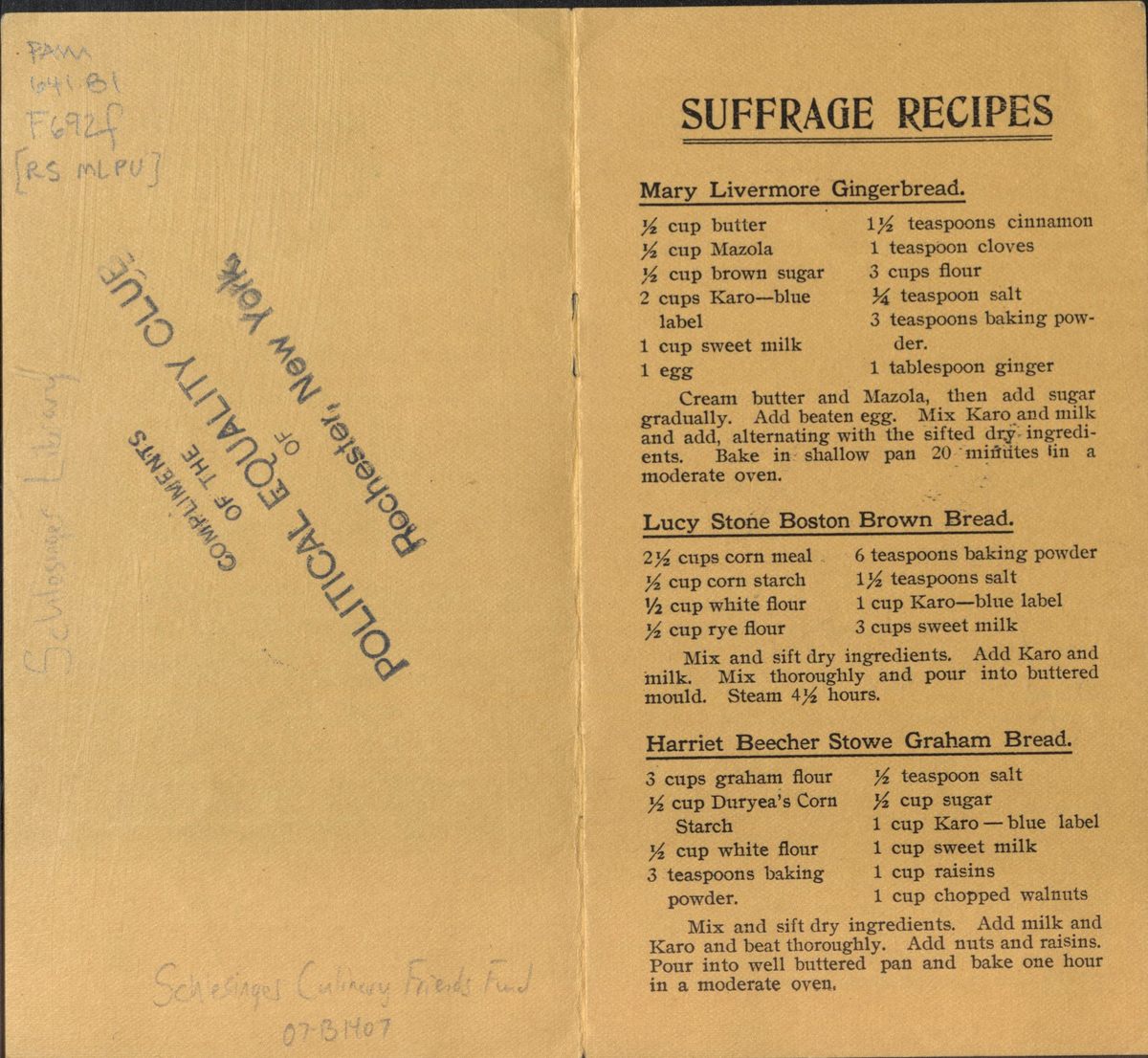

This recipe comes from Karo corn syrup’s “For Better Baking” pamphlet, published in 1913. “Respectfully dedicated to votes for women,” the pamphlet contains recipes named for prominent suffragists, including Harriet Beecher Stowe Graham Bread, Lucy Stone Boston Brown Bread, and this one for “Aunt Susan Marble Cake.” Named for leader Susan B. Anthony, the dense, spiced loaf goes well with coffee.

For the light batter:

¼ cup butter, softened to room temperature

½ cup sugar

¼ cup whole milk

1 cup flour

1 teaspoon baking powder

½ cup corn starch

½ teaspoon vanilla

3 egg whites, at room temperature

For the dark batter:

¼ cup butter, softened to room temperature

½ cup dark brown sugar

¼ cup whole milk

1 cup flour

1 teaspoon baking powder

½ cup corn starch

1 teaspoon each of ground cloves, cinnamon, nutmeg, and mace

½ cup dark corn syrup (If you don’t have corn syrup, maple-flavored syrup or a 1:1 ratio of honey and molasses will work.)

3 egg yolks

1. Preheat the oven to 325°F (163°C).

2. To make the light batter, cream the butter with the sugar. Sift the light batter’s dry ingredients into the mixture, alternating with the milk, then add the vanilla. Beat the egg whites until they’re stiff, then fold them into the mixture. Set the light batter aside.

3. In a separate bowl, repeat the steps above with the dark batter’s ingredients. After the milk and flour have been added to the dry ingredients, add the corn syrup, then beat the egg yolks and add to the mixture.

4. Grease and flour an 8.5 by 4.5-inch loaf pan. Pour in about ½ cup of light batter in an oval shape, covering almost the entire bottom of the pan. Take the dark batter and pour in just enough to form a slightly smaller oval on top of the light batter. Continue pouring increasingly smaller ovals, alternating light and dark, until the loaf pan is about two-thirds full.

5. To make the marbled pattern, take a toothpick or sharp knife and trace a curved, S-like path back and forth across the batter’s surface. Rotate the pan 90 degrees and repeat the curved path in the opposite direction, allowing the lines to intersect. Bake for 60 minutes, or until an inserted toothpick comes out clean.

Suffrage Angel Cake

Adapted from a recipe by Eliza Kennedy in The Suffrage Cook Book

Eliza Kennedy was a Pittsburgh-based suffragist. Though not as famous as the mainstream heroes of the movement, Kennedy was such a force in fighting for a variety of local civic causes that her opponents called her a “she-devil.” In between making speeches, serving on a League of Women Voters committee, and planting suffrage gardens, Kennedy also honed her skills making a light, vanilla-inflected angel food cake.

11 egg whites, room temperature

1 full cup cake flour (or use substitute mentioned below)

1½ cups granulated sugar

1 heaping teaspoon cream of tartar

2 teaspoons vanilla extract

1 pinch of salt

1. Preheat the oven to 325°F (163°C). Sift the cake flour nine times. (If you don’t have cake flour, take one cup of all-purpose flour, remove two tablespoons and replace with two tablespoons of cornstarch.) Then sift the granulated sugar seven times. Modern cooks can opt instead to pulse the sugar in a food processor. The latter approach also makes the sugar less coarse, which helps ensure the proper structure of the cake. Sift it one or two times afterward to get rid of any remaining lumps.

2. Whisk the egg whites in a bowl. When they’ve reached a frothy texture, gradually add in the cream of tartar, salt, and sugar until the mixture is light with soft peaks. Then add the vanilla.

3. Sift part of the flour into the egg whites, then fold the whites into the flour. Repeat until all the flour is blended.

4. Pour the mixture into an ungreased angel food cake pan. Kennedy’s recipe calls for putting the cake into an oven “with very little heat,” and gradually increasing the heat every five minutes for 30 total minutes. Instead, you can just cook at 325 degrees for about 30 to 40 minutes, until a toothpick inserted into the cake comes out clean.

5. When it’s done, place a plate on your counter and rest the cake pan upside-down to cool (this position prevents the cake from deflating). Once it’s cool, run a knife around the pan’s edge and lightly hit the pan to guide the cake out. For extra flavor, garnish with berries and whipped cream.

A version of this story originally appeared on August 18, 2020. It was updated in March 2022 to include an additional recipe.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook