After a Century Abroad, a Collection of Cuneiform Is Heading Home to Iraq

Some will remain in Philly, but only because they might be too fragile for the trip.

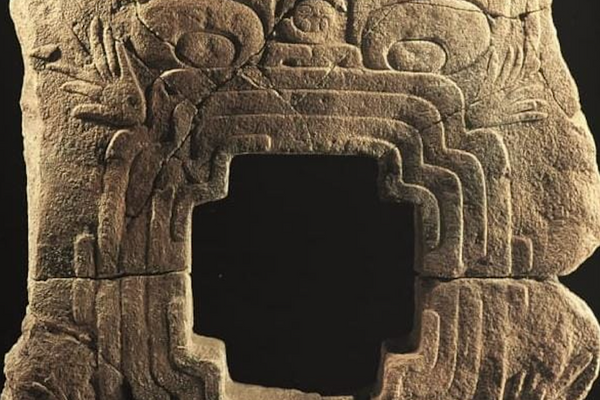

In 1922, the same year that Tutankhamun’s tomb was opened in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings, excavations by Philadelphia’s Penn Museum and London’s British Museum began on the ruins of Ur, a major city-state of ancient Mesopotamia, in what is today Iraq. On the site, archaeologists found thousands of clay fragments incised with cuneiform, the Mespotamian script that had been used to document everything from the Code of Hammurabi to mundane transactions between neighbors. (The fragments, which date to about 2000 B.C., are even older than Hammurabi’s landmark code of laws.) Many of the pieces were shipped to the Penn Museum for translation. Though some had eventually made their way back to Baghdad, many stayed put in Philadelphia—until now.

“The agreement [at the time] was half the artifacts stayed in country, and half stayed at the excavating institutions,” says archaeologist Brad Hafford, a research associate at the Penn Museum who manages the Ur Online digitization project at the museum. “What they decided is all the tablets they would ship out of Iraq, because no one in Iraq could read them. And of course [reading the tablets] takes a long time.”

How long exactly depended on the condition of the tablet fragments. Archaeologists got through the more intact inscriptions—mostly bureaucratic records—relatively quickly and published their findings in 1937. Other pieces, however, were good and smashed (in antiquity), so it took a long time to make sense of them, reports the Philadelphia Inquirer. Those took until 1976.

By 1991, thousands of the original collection of 7,500 clay inscriptions that made the trip to Philadelphia had been returned to Iraq, where there are now plenty of scholars who can read them. The 4,000 or so fragments that remain are some of the most delicate items, and that’s the main reason they’re still in the United States. But the museum is working to get more back, especially the ones that are most likely to survive the trip. “Clay tablets break up pretty easily. They didn’t bake these, they just dried them in the sun,” Hafford says. “What we’ve done now is look for the ones that can travel the best.”

On December 4, 2019, 387 tablet pieces will first head to the Iraqi embassy in Washington, D.C., and from there will depart on the 6,200-mile journey back to Baghdad, where they will reside in the Baghdad Museum. To ensure safe passage, researchers at the Penn Museum have made the clay as comfortable as possible.

“We have these boxes that are lined with foam, little bubble wrap pouches … It’s almost like a filing cabinet,” Hafford says—which seems fitting for what are essentially administrative records. The trays are then themselves packed in more foam. The most fragile fragments will continue to live at the Penn Museum for now, until Iraqi and American archaeologists figure out how to get them back across the world intact.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook