The Vikings Got Lucky and Hit Greenland During a Warm Spell

But it didn’t go well for them when things got cold again.

The Vikings of popular lore and actual history line up in some ways, and not so much in others. They were indeed, for example, often blonde, since they used lye to lighten their hair. But a vast majority weren’t berserkers leaping from ships, salivating for a good sacking, but rather humble rye and oat farmers, traders, and craftspeople. And they probably weren’t particularly fond of the cold.

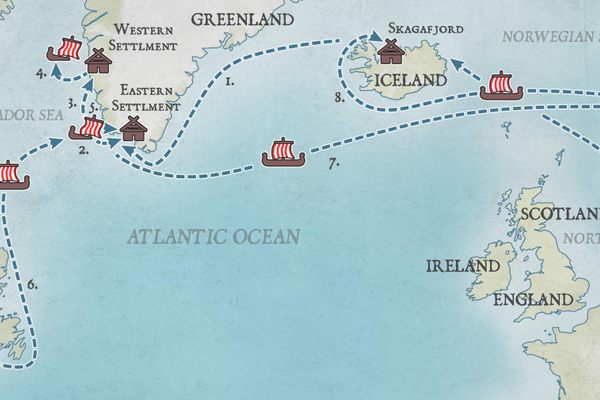

A study recently published in the journal Geology suggests that when Vikings settled in Greenland, between 985 and 1450, they benefited from an unusually warm spell. A team of scientists from Northwestern University reconstructed a climate record for southern Greenland for the past three millennia and found that the Viking period in Greenland was, climatically, unlike anything seen before or after. Vikings may have enjoyed balmy 50-degree-Fahrenheit summers, similar to modern Greenland, which is thawing at an alarming pace.

“It’s long been speculated that climate changes help explain when the Norse settled in Greenland, and why their colonies died out,” says Yarrow Axford, senior author of the study, of Northwestern University, via email. “But data from the local area were rare, so a lot of this was based on assuming southern Greenland experienced temperature shifts that mirrored those in Europe.”

Axford explains that recent studies tend to support the idea that glaciers were growing in Greenland when Vikings settled, suggesting a cooling was underway. However, she believes the opposite took place: “We find evidence for warming around the time the Norse came to Greenland, and cooling and climate instability around the time their settlements collapsed.”

The analysis is based on the head capsules of a certain lake fly, called chironomids, or non-biting midges. When these mosquito-like insects die, they can be preserved in lake sediment layers. By pulling cores from Norse settlements outside the town of Narsaq, the team was able to examine the oxygen isotopes in chironomid remains, which they used to track climate fluctuations.

The team suspects the warming trend was related to ocean currents around southern Greenland, so the phenomenon may have been quite localized.

What makes this discovery even more intriguing is that it could provide evidence as to why the Vikings abandoned their Greenland settlements. After enjoying a relatively mild climate, things would become much tougher as temperatures began to plummet. While Yarrow did allude to other factors contributing to the decline of the settlements—conflict, diet, trade—her research brings a new dynamic to the table.

“What we’ve added to the story is direct evidence for warmer conditions at the eastern settlement while the Norse thrived there than before and after,” she says. “And our results also suggest cooling and an extremely variable climate at the time the settlements died out. It’s a really intriguing correlation, but it doesn’t pinpoint the cause. Archaeological evidence would have to do that.”

There are still chapters of the saga yet to be written.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook