Revisiting the Weird and Wonderful Nature of 2022

This year, we met creatures (and other living things) great and small, from the world’s largest organism to microscopic parasites.

A ruthless parasite sprouting from the exoskeleton of an unfortunate fly. An egg-laying mammal—not a platypus—that uses “jazz hands” as a defensive tactic. Iguanas that have evolved to ride the waves—meriguanas, if you will. These are just a few of the fascinating organisms we shared with readers this year.

Sometimes, an entire species intrigued us, such as the venomous but (relatively) docile golden lancehead viper, a critically endangered snake that lives only on one tiny Brazilian island—for now. Sometimes, an individual organism caught our attention by going above and beyond scientific expectations, such as an ultramarathoning Arctic hare or the hauntingly beautiful Alerce Milenario, a cypress so old it likely predates the first monuments at Stonehenge. From single-cell parasites that can control a host’s behavior to the Humongous Fungus, considered the largest living thing on the planet, nature gave us plenty of wonder this year.

Here are some of our favorite 2022 stories of living things that made us say “Wow,” “Whoa,” and, occasionally, “Nope.”

Meet Florida’s Most Adorable Rodent and the Superfans Determined to Save It

by Karuna Eberl

Spare a thought for the Key Largo woodrat. The photogenic rodent, found only on the north edge of the Florida Keys, has endured habitat destruction, invasive predators, and other existential horrors. It’s likely these chunky foot-longs wouldn’t even be around were it not for some unexpected assistance from a couple of retirees who taught themselves how to save the sweet-faced animals.

Hawaiʻi Tackles Invasive Little Fire Ants With Vigilance, Slingshots, and Gooey ‘Sputter’

by Ashley Stimpson

Considered one of the world’s worst invasive species, Wasmannia auropunctata, or the little fire ant, is about the size of a sesame seed. Its sting packs an outsized punch, however: Each worker can zap targets multiple times with painful venom that has earned them the nickname “electric ants.” Across Hawaiʻi, finding infestations of the tiny terrors—and stopping their spread—is a sticky business. It starts with peanut butter and Spam.

Snake Island’s Venomous Vipers Find a New Home in São Paulo

by James Hall

Off the coast of Brazil, Ilha da Queimada Grande is a small, rugged island notorious for being home to the only population of highly venomous golden lancehead vipers (Bothrops insularis). But Snake Island is no longer a safe place for the animals, which are critically endangered and sought by poachers. To save them from extinction, researchers have hatched a plan to create a captive population right in the heart of one of Brazil’s largest cities.

What Energized This Arctic Hare to Keep Going and Going and Going?

by Gemma Tarlach, Senior Editor/Writer

Fluffy, chubby, impossibly cute, the Arctic hare known to researchers as BBYY doesn’t look like an ultramarathoner. But she’s earned her place in science as a record-smashing icon. Most hares, rabbits, and related animals are homebodies, staying close to their places of birth. A couple of species venture about 20 miles from home if needed. At the northern edge of Canada, BBYY logged more than 240 miles in 49 days, shocking the team tracking her—and forcing a rethink of what we know about her species.

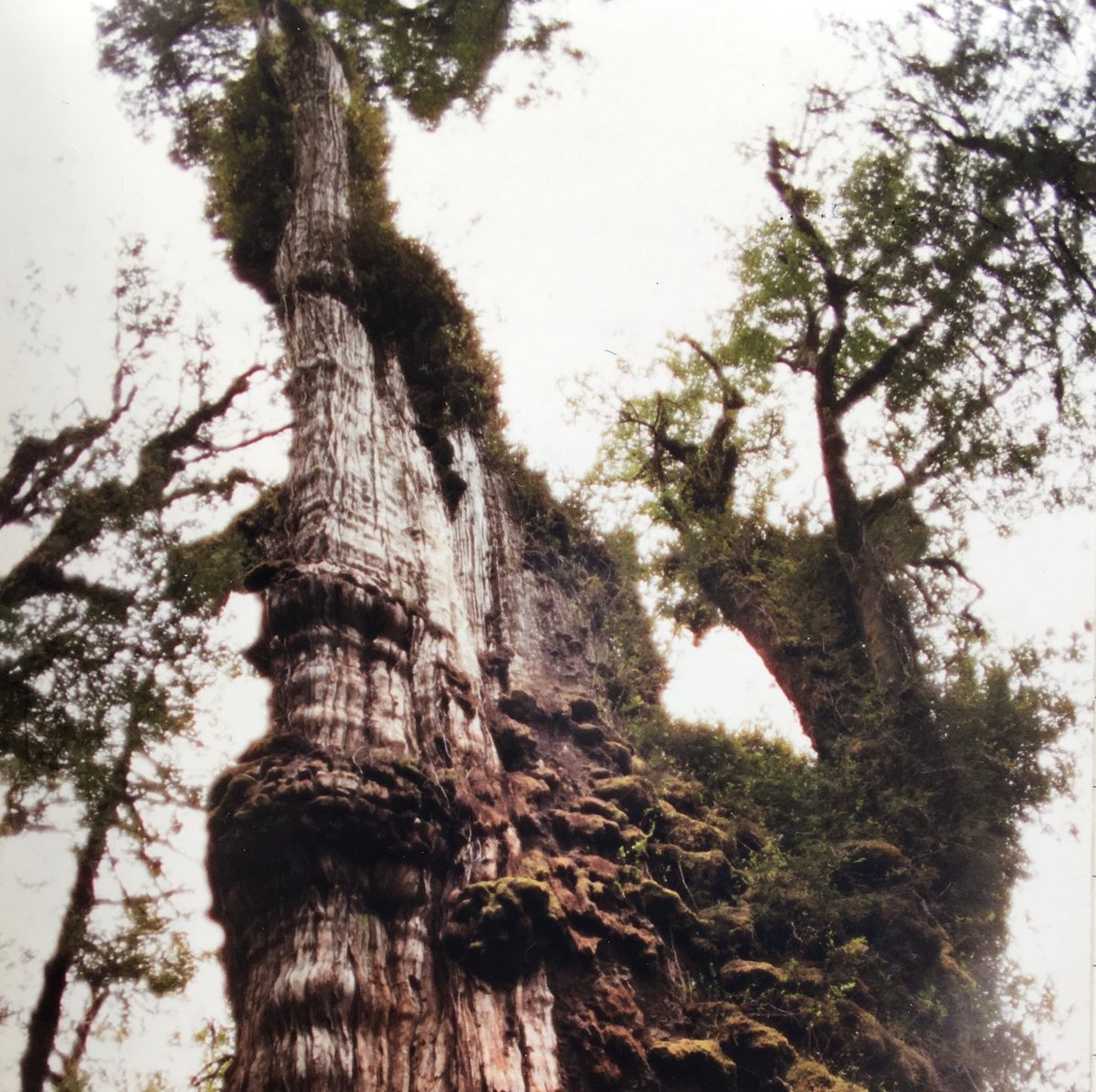

Is the World’s Oldest Tree This Stately Cypress in Chile?

by Eden Arielle Gordon

Rising nearly 200 feet like the magnificent ruins of a medieval tower, the Alerce Milenario, a Patagonian cypress, is ancient. Just how ancient is up for debate, but a new model suggests it may be close to 5,500 years old, which would make it the world’s oldest known tree. Maybe. Not everyone agrees with the researchers’ methods to determine the Chilean contender’s birthday. And some scientists would define “tree” differently to include Pando, a grove of quaking aspen clones that may be 80,000 years old.

Why the Echidna is Australia’s Most Delightfully Different Mammal

by Jack Ashby

In this excerpt from his book Platypus Matters: The Extraordinary Story of Australian Mammals, zoologist Jack Ashby introduces us to an animal once thought to be some kind of hedgehog gone terribly wrong. But the echidna has ambled its own evolutionary path, developing an anteater-like snout and rear-facing back feet (which it can twist up and over its back for grooming, surely the envy of even a housecat). Then there’s its unique defensive behavior: To protect itself from predators and pesky researchers, it does “jazz hands” with all four feet, burrowing vertically down into the soil, leaving only a back of sharp quills exposed.

Marine Life in the Galápagos Gets a New Protected ‘Ocean Highway’

by Winnie Lee, Visuals Editor

Ecuador’s famously biodiverse archipelago may be best known for finches and giant tortoises, but there’s a whole other world beneath the waves. Uniquely adapted marine iguanas, penguins, sea lions, and other animals can be seen along the islands’ coastlines, while silky sharks, spotted eagle rays, and scalloped hammerheads ply deeper waters nearby. As of January 2022, all of them are benefitting from a massive expansion of protected waters. The new Hermandad (“Brotherhood”) reserve protects crucial migration routes between the Galápagos and key habitats near the Central and South American mainland.

What the World’s Largest Organism Reveals About Fires and Forest Health

by Colin Hogan

Almost invisible to someone standing right on top of it, the Humongous Fungus of Oregon’s Blue Mountains covers nearly four square miles and weighs at least 7,500 tons (some researchers believe it may weigh as much as 35,000 tons). The single specimen of honey mushroom (Armillaria ostoyae) exists mostly underground as a network of fine filaments. The parasite surfaces only when it invades trees, eventually killing them from the inside out. As it eats its way across Malheur National Forest, the Humongous Fungus is a big problem—but also a chance to learn how our fire management practices may have made this monster.

Real Zombies and Body Snatchers Live Among Us

by Gemma Tarlach, Atlas Obscura Senior Editor/Writer

It’s not quite Dawn of the Dead, but around the world, hundreds of parasitic species have evolved ways of controlling their hosts. Microbes such as lyssaviruses cause inflammation in the brain, which can make a host more likely to engage in risky behavior that ultimately benefits the parasite, while numerous species of fungus build their own communication network within the insects they invade. One particularly disturbing wasp species precision-targets a spot in a cockroach’s nervous system that renders it unable to control its movements and then rides it home using the roach’s antennae as reins. Giddyup.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook