The Indigenous Tribes Fighting to Reclaim Stevia From Coca-Cola

Guaraní have long cultivated the plant, which they introduced to a world hungry for natural sweeteners.

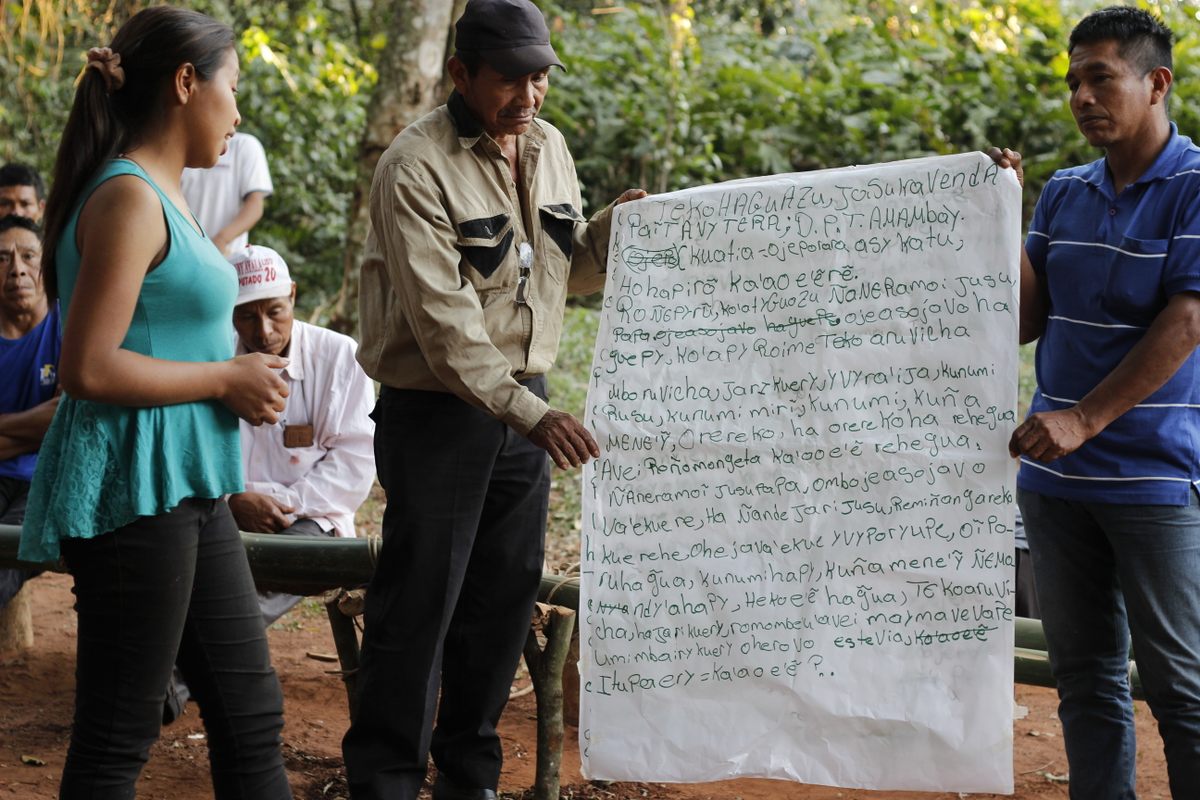

Luis Arce steps into the center of a sacred grove of trees on a high hilltop in Paraguay’s Amambay highlands. Wearing black cowboy boots, a faded baseball cap, and an off-white polo shirt tucked into navy-blue khakis, the 67 year old greets a crowd of more than 100 fellow Paî Tavyter’a and Kaiowá. He is the leader of the region’s 15,000 indigenous Guaraní.

“We have gathered here at the Yasuká Vendá—the sacred spot where our great eternal grandfather, Ñane Ramõi Jusu Papa, laid his footsteps and created the Earth—to talk about the corporate usurpation of our traditional knowledge of the ka’a he’e,” says Arce. He’s using the Guaraní name for a sweet wild herb that’s known around the world as an ingredient in reduced-sugar teas, candies, and soft drinks: stevia.

Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, and other companies have used the sugar alternative—which came from Guaraní lands, where it’s been used as a ceremonial medicine and sweetening agent for centuries—to build an estimated $492 million a year industry. Despite this provenance, acknowledged in marketing materials by images and descriptions of Guaraní traditions, the Guaraní have never been consulted or compensated in any way.

“These companies took our [traditional knowledge] and are using it to make vast profits,” continues Arce. He outlines the case for a lawsuit and demands restitution. The crowd responds with a standing ovation. The year is 2015.

Over the next three days, the group drafts an international declaration. They are aided by lawyers and advisors from universities and nonprofits, including Miguel Lovera. A scientific advisor to the Center for Research on Rural Law and Agrarian Reform of the Catholic University of Asuncion (CEIDRA), Lovera has spent more than 20 years advocating for indigenous rights in Paraguay.

“What needs to be understood is that we are talking about a small, obscure herb with a very limited natural range,” says Lovera. Wild stevia grows in remote northeastern highlands along the border of Paraguay and Brazil. While not exactly unpleasant, the plant’s aroma is often referred to as “goat’s scent” by indigenous populations. The pungency does not suggest sweetness. “Western scientists did not ‘discover’ the usefulness of this plant—they were introduced to it by the Guaraní.”

What’s more, ka’a he’e is an anomaly. Though more than 230 species of stevia have been identified, says Lovera, “this variety alone possesses such sweetness. It has served as the basis for all subsequent research.”

Put another way: Without the help of the Guaraní, there would be no stevia industry. But the plant is now critically endangered in the wild. Arce and the Guarani hope a lawsuit will help them save stevia’s native habitat and rescue the wild plant from extinction.

For the Guaraní to make their case against Coca-Cola and other companies, they must argue that stevia is, effectively, their intellectual property. Laying claim to a wild herb may sound odd, but, Lovera says, the group’s centuries-old relationship with ka’a he’e makes it clear that all modern stevia usage derives from their traditional knowledge.

“If you ask a member of the Paî Tavyter’a about the origins of their relationship to stevia, probably they will shrug and tell you, ‘It has always been that way,’” he says. The group believes plant usages were revealed to spiritual leaders in the time immemorial.

Lovera explains the origins of the relationship from an evolutionary perspective. Historically, the group was semi-nomadic. They relied on remote forests for foraging, building materials, protection, and game. Wild foodstuffs supplemented crops such as maize, cassava, and sweet potatoes. Seeking to minimize labor and ecological impact, Guaraní settled in mountain grasslands abutting dense subtropical forests, which supported their mix of agriculture and foraging.

“And this is precisely the habitat of the ka’a he’e,” says Lovera. The spindly herb grows one to two feet in height and thrives at high elevations in sunny transitional zones along forest edges. For groups such as the Paî Tavyter’a, its abundance signified a blessed location. According to Arce, the plants marked “the place we were intended to be.” Stevia’s sweetness came to be associated with divine beneficence, and it took a central role in rites of passage.

“We use the ka’a he’e in our initiation ceremonies,” says Arce. “When a boy grows into a young man, he washes his hands and arms in a cold infusion [prepared with its leaves], guaranteeing his crops will always be sweet and abundant. Young women use it for purifying themselves when they become adolescents. They have sessions that include drinking water infused [with ka’a he’e] and washing their bodies with it.”

Other uses are more utilitarian. The Guaraní employ stevia medicinally as an antiseptic, digestive aid, astringent, and antiparasitic. Recreationally, Guaraní chew leaves as a treat and use them to sweeten traditional yerba mate tea—a bitter, highly caffeinated herbal drink of their invention.

“Tasting ka’a he’e for the first time is something I remember very well,” says Arce. Given the plant’s religious status, and its 200-times-sweeter-than-sugar leaves, the experience made an impression. “The taste was like no other,” laughs Arce. Stevia’s sweetness comes on slow; has a longer duration and later peak than sugar; and provokes a slightly bitter, licorice-like aftertaste. “I know that I am taking something into my body that [is holy],” he says. “That too was a very special feeling.”

For centuries, the Guaraní cultivated stevia and used its leaves as a sweetener. But if you peruse global patent registries, you’ll find people and groups credited for inventing the extract now used around the world, and it’s never Arce, his people, or his ancestors. Instead you’ll find names such as Coca-Cola, PureCircle USA, and HYET Sweet.

“PureCircle alone has more than 400 proprietary stevia-related patents and patents pending,” says sociologist and Paraguayan intellectual property lawyer Silvia Gonzalez. As CEIDRA’s lead legal advisor, she helped Arce and the Guaraní draft their declaration, and is now working to lay the groundwork for international lawsuits. This failure to recognize the Guaraní, Gonzalez says, is rooted in colonialism and the Eurocentric patent system.

According to University of Illinois professor of pharmacology Djaja Djendoel Soejarto, ka’a he’e probably entered the written record around 1570, as Spain established a capital in Paraguay. In a book titled Natural History of New Spain, physician Francisco Hernández noted a wild herb that, when chewed, exhibited an uncanny sweetness. This was likely stevia.

Further interest and investigation by outsiders stalled, though, due to the introduction of sugarcane. It took another 300 years for westerners to recognize ka’a he’e’ as a potential sugar substitute.

“In 1887, during my explorations of the extensive forests of eastern Paraguay,” wrote Swiss-Italian botanist Moisés Santiago Bertoni in 1918, “I heard references about this plant [and its characteristic sweetness] from herbalists (yerbateros) from the northeast, and Indians from the Mondaíh.”

Bertoni quickly mounted an expedition. His enthusiasm derived from timeliness: The first artificial sweetener, saccharin, had been synthesized from coal-tar derivatives in 1879. But much like today’s leading artificial sweeteners—namely, sucralose (Splenda) and aspartame (NutraSweet)—its artificiality raised safety concerns. (American President Theodore Roosevelt, prescribed a sugar-free diet, was a fan, and clashed with a government chemist who condemned saccharin as “injurious to health.”) Then as now, interest in natural alternatives was high.

Two World Wars and a (temporary) exoneration of health concerns about saccharin stymied progress, but by the early 1930s, chemists had isolated ka’a he’e’s sweetening compounds. Commercialization of extracts began in 1977, with Japanese scientists leading the way.

“In the early ‘70s, two visits alone resulted in the extraction of at least 500,000 wild plants,” says Lovera. With stevia next to impossible to grow from seed, the Japanese “dug up whatever they could find and took it with them.”

Arce remembers the arrivals bitterly. At that time, infringement upon Guaraní territory was a relatively new development. Visitors were rare. The Paî Tavyter’a greeted scientists warmly and freely shared their knowledge of the ka’a he’e.

“That was a big mistake,” says Arce. “We showed them the plants and they started digging without so much as asking permission. The corrupt government allowed them to dig on our land, and they did so time and again.”

In Japan, usage skyrocketed—and soon accounted for an estimated 40 percent of the sweetener market. Stevia spread globally throughout the 1980s. Following a four-year ban citing poor toxicological information, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved it as a dietary supplement in 1995. Similar conditions prevailed there and in Europe until the mid-2000s, when global concerns about rising rates of diabetes and obesity spurred further research. In 2008, the FDA authorized stevia as a sweetener. The European Union followed suit in 2011.

By 2012, stevia-based products ranked second among the world’s sugar substitutes. Hoping to combat steep drops in soda consumption, beverage titans including Coca-Cola and PepsiCo raced to offer diet products sweetened with 100 percent stevia. The first—known as Coke Zero Stevia—launched in limited-release last year. This push made stevia a household name and fueled an economic boom. Industry reports project stevia revenues will grow to $801.7 million by 2026.

Lovera says the Paraguayan government aided and abetted the foreign plundering. Worse, in turning a blind eye to the Guaraní’s intellectual rights, it failed to capitalize on a growing industry.

Though stevia originated in territories traditionally belonging to the Guaraní, they are in no way involved in the commercial cultivation of the plant. As a whole, Paraguayan farmers grow fewer than 6,000 acres a year. China, meanwhile, furnishes around 80 percent of the world’s crop.

“As the center of origin, it’s tragic to see how our country has squandered this opportunity,” says Lovera. Serving as an advisor for the Paraguayan Ministry of Agriculture from 2008 to 2012, he pushed for stevia patents, protections, and investment. Mostly, he says, his suggestions were unheeded. Without governmental support, small farmers cannot effectively transition to growing and selling stevia.

“It is too labor intensive and not profitable enough to grab the attention of plantation owners, but, for our peasant farmers, it could be very helpful,” explains Lovera. The problem is, growing at scale requires about $10,000 of investment. “You need special irrigation,” he continues. “Stevia prefers well-drained soils, but you cannot allow one bit of sun-stress. Therefore, irrigation must be extremely precise.”

With growers in the U.S., Korea, Kenya, India, and elsewhere entering the market, competition is fierce.

“Creating a geographical indication could help Paraguayan farmers stand out,” says Lovera. But with little government interest, “We are left with a humiliating failure: Our nation introduced stevia to the world and has nothing to show for it.”

It is a bitterness Arce knows well.

What Japanese scientists began intensive logging has continued. Forests have been cleared to make way for large-scale cattle ranches, sugarcane plantations, and soybean production. Formerly abundant, ka’a he’e is now critically endangered in the wild.

“When I was a boy, the Yasuká Vendá, [our sacred center of origin], stood at the heart of a vast wilderness,” says Arce. “Now, it is like a tiny island floating in a sea of decimation.”

Arce calls the declaration issued by the Guaraní a last-ditch effort to save what’s left of the ka’a he’e. He hoped consumer attention would pressure corporations to pursue a benefit-sharing agreement, but invitations for discussions have largely been ignored. Now, he’s working with Gonzalez and others to pursue international lawsuits.

Michael F. Brown is the president of the School for Advanced Research in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and one of the world’s leading experts on cultural appropriation. He describes the Guaraní’s situation as a classic case of biopiracy, which, at its most basic level, is “when knowledge from indigenous communities is taken by an outside individual or group who then claim to ‘own’ that knowledge and are able to then sell it for a profit.”

Though biopiracy dates to the colonial era, instances rose dramatically throughout the 20th century, as U.S. law changed to allow new plant varieties to be patented (the first time in history a living organism could be patented) and extended these protections to genetically modified organisms, with other legal systems following suit. (For Coca-Cola, PureCircle, and others, their patents are for stevia extracts they developed from ka’a he’e.) The end result is wealthy companies profiting from and taking credit for the knowledge of indigenous communities of the global south.

Brown describes the stevia case as egregious biopiracy. And it is the establishment, over the past several decades, of biopiracy in legal codes that has given the Guaraní and advocates such as Gonzalez hope that a lawsuit could work.

“We have an excellent precedent where indigenous people from Peru won back the rights to their traditional knowledge concerning Lepidium meyenii from a U.S. company in 2007,” Gonzalez explains. Similar to stevia, the case involved extracts taken from the maca plant. “Lawyers were able to use the 2007 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, the 1993 Convention on Biological Diversity, and [pertinent U.S. legislation] to argue the patent derived from biopiracy and have it revoked.”

But in that case, indigenous populations had government support. Peru had passed laws suggested by the UN that lent validity to complaints voiced with the World Trade Organization and made international lawsuits possible. Paraguay hasn’t acted. Barring new legislation, the Guaraní are powerless.

“The next step is for the government to ratify the UN’s Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit Sharing and pass all recommended legislation,” says Gonzalez. The Protocol has been ratified by 104 nations and the European Union—though the U.S. has yet to sign. “We could then pursue legal action against companies profiting from the use of stevia patents.”

Lovera has his hopes, but remains skeptical.

“In practice, the Paraguayan government does not care about the rights of its indigenous people,” he says. Corruption has allowed agricultural bosses to usurp more than half the lands constitutionally recognized as belonging to the Guaraní. Falsified titles and deeds of sale are routine. “Of course, we have fought this tooth and nail,” says Lovera. “But judges and officials, they turn a blind eye.”

For his part, Arce chooses to believe the wrongs will be righted: A benefit-sharing agreement would protect the ka’a he’e and ensure the survival of his people.

“Today, we are both in danger of disappearing,” he says. “What is crucial is for us to recover our territory, which is the territory of the ka’a he’e. Though the land is rightfully ours, we would gladly pay the ransom and set it free from those that have done it nothing but harm. To live off the land and see it restored, that is our dream.”

If that happened, Arce says the Guaraní could delight in the world’s enthusiasm for stevia. For now, its adoption is a worldwide emblem of their dispossession.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook