For Sale: President William McKinley’s Top-Secret Autopsy Report

After McKinley’s assassination, a local Buffalo coroner was called in to tell the nation how the 25th president died.

The Buffalo Medical College laboratory was under guard, and the few scientists permitted entrance had been ordered not to discuss the experiments underway inside. Among the most reticent of them was Dr. Herman Matzinger, who told a journalist only that he “would have no leisure from his work,” the Buffalo Courier reported. It seemed like no one had rested since President McKinley died in the early morning hours of Saturday, September 14, 1901.

Eight days prior Leon Czolgosz had shot McKinley twice, at close range, in front of hundreds of witnesses at the Pan-American Exposition. But, improbably, the president survived the attack and after long days of uncertainty, his recovery had seemed likely. Now it fell to Matzinger and his colleagues to explain to a stunned nation exactly what had happened—and to do so quickly. Already a theory was circulating that the president had been felled by an anarchist’s poison-tipped bullets.

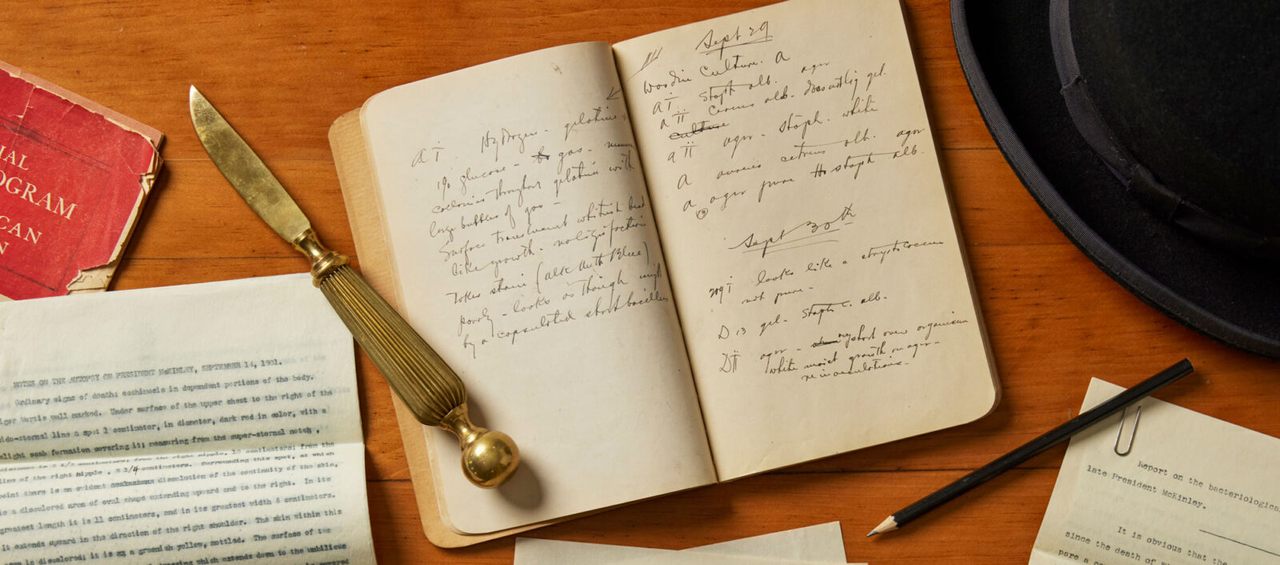

In the laboratory at Main and High Streets, Matzinger examined the nickel-plated revolver the assassin used. He touched a bullet to a medium he had prepared for growing any bacteria present and dunked the gun’s cartridge in a similar solution. He analyzed samples taken from the president’s wounds and injected them into lab animals to evaluate their toxicity. And he recorded each step of the process in quick cursive inside a composition book. On the marbled cover a label announced: “Dr. Matzinger’s Notes on President McKinley’s Case.”

That’s some of what Nathan Raab saw when he looked at pictures of the documents provided by one of Matzinger’s descendants more than 120 years later. The historical document dealer’s reaction? “Wow.”

When the phone rings at the Raab Collection, the historical documents company Nathan Raab runs with his parents and wife in the suburbs of Philadelphia, he never knows what discovery might await. Over the past 35 years, the company has been involved in, among many other transactions, the sale of a letter from Theodore Roosevelt in which the then-governor of New York first referenced the phrase “speak softly and carry a big stick”; scientific manuscripts filled with equations handwritten by Albert Einstein; and an official entry form for the 1936 National Air Races, filled in by Amelia Earhart, the year before she disappeared.

For collectors, the value of documents such as these often lies in those famous signatures. That wasn’t the case with the Matzinger collection. Herman Matzinger may have been well known in Buffalo before President McKinley’s assassination—he had attended school and built his career as a physician and professor in the city; his wife Mary’s Tuesday afternoon teas were a fixture of the society page—but few others had heard of the 41-year-old man before he was recruited to be one of two doctors to autopsy the fallen president in the hours after his death. Today, Matzinger doesn’t even rate a Wikipedia page.

But sometimes, the history is enough to draw document collectors. “This is an important piece of American history,” Raab says, explaining his own interest in the collection. “McKinley’s death ushered in a very important era,” the presidency of Theodore Roosevelt. That, plus the rarity of the find—notes on a presidential assassination never before seen outside of the doctor’s immediate family—intrigued Raab.

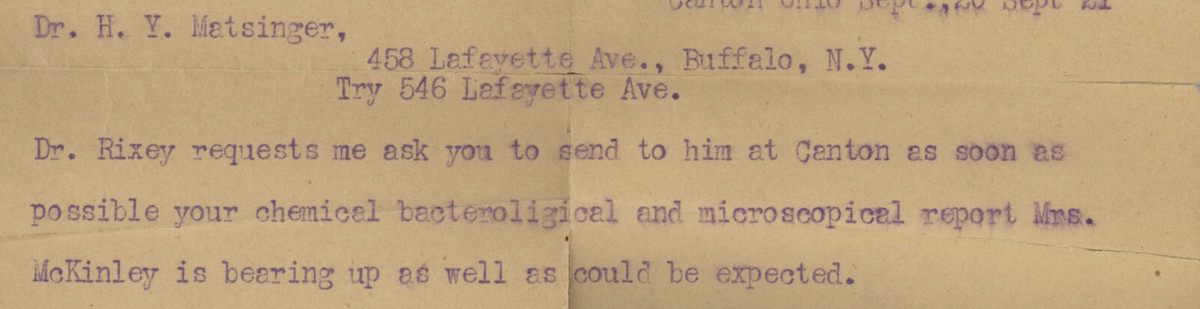

The Matzinger descendent who contacted the Raab Collection, who wishes to remain anonymous, knew through family lore that one of her relatives had played an instrumental role in the days after the McKinley assassination, Raab says, but she had long been unaware of exactly what materials had been preserved and handed down within the family. On closer examination, she found a trove: Matzinger’s notebook, detailing his bacteriological experiments, as well as his draft and final findings; official reports on the death; correspondence with others involved in the investigation (“Mrs. McKinley is bearing up as well as could be expected,” reads one telegram encouraging Matzinger to conclude his study quickly); and an invitation to the president’s funeral in Buffalo.

On September 15, 1901, 24 hours after he had conducted McKinley’s autopsy in the same house, Matzinger paid his last respects to the man. The following day, McKinley’s body was transported to Washington, D.C. where it would lie in state; Matzinger was in his lab. The 25th president of the United States was later laid to rest in Canton, Ohio.

When presented with a collection such as this, a historical documents dealer must first authenticate the materials. In his career, Raab has seen both intentional forgeries and unintentional fakes—when the story of a document’s origins morphs through the generations until the living family is convinced of its authenticity. The biggest challenge these days is high-quality reproductions, which are difficult to spot in digital photos or scans. When the Raab Collection is interested in a document, they ask to examine it in person. The paper is the key. With the Matzinger collection, there were several points of reference: “The telegram should have a different paper consistency, for instance, than a carbon copy, which was also present, and should be different than the actual notebook,” Raab says. It was the real thing.

The second task for a historical documents dealer is putting a price tag on history. “Pricing things like this is art, not science, and it requires a great deal of understanding of what the market will bear and what is important and what is not,” Raab says. He imagined the ideal buyer for this collection would be a scholar or someone who would share it with the scholarly community. Matzinger submitted his conclusions to the government—there was no poison, and any infection the president had suffered from developed after the shooting. (Today, historians believe McKinley died from pancreatic necrosis, a condition which could not have been treated in the early 20th century.) But Matzinger apparently did not see the public value in his notes on his process. “In retrospect, as 21st-century historians, we can look back and say ‘all, that is important information too,’” Raab says.

The Raab Collection bought the Matzinger papers for an undisclosed price and has listed the collection for sale on its website for $80,000.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook