About

In 1976, the 19 tribes that make up New Mexico's Pueblo population gathered to open Albuquerque's Indian Pueblo Cultural Center on a patch of Native American land in the center of the city. This serene complex of stucco buildings is an important arena for the preservation of Native American crafts, music, and ceremonies. It's also a place where all-too-rare pre-Columbian cuisine is sustained and celebrated, on the menu at Indian Pueblo Kitchen.

The year 1492—when Christopher Columbus arrived in the Americas—divides the dinner menu. "Post-Contact" options feature all the burgers, salads, and mixed-Mexican options you'd expect from a New Mexican restaurant. The "Pre-Contact" menu, on the other hand, eschews the staple beef, chicken, wheat, butter, sugar, and rice that anchor "American" cuisine altogether; it's a love letter to New Mexico's original inhabitants, a smattering of indigenous ingredients upheld and shaped by modern culinary techniques.

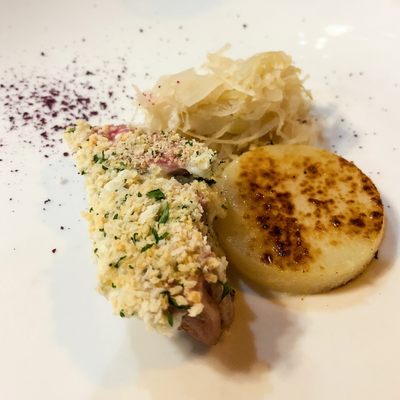

Diners eating off the Pre-Contact menu can open with a carpaccio, comprised of sumac-seared bison, pickled squash, and pumpkin oil, before moving on to a pot roast of elk shoulder, acorn squash, and wilted wild greens. Another entrée option, the "Tribal Trout," is pan-seared and served with yam puree, prickly pear syrup, and fried sweet potato strings. Visitors can finish with their wojapi, slow-stewed berries baked under a maple pepita-and-pecan-crumble crust. With its commitment to authenticity, the menu revels in what most modern kitchens might see as a limitation. Indigenous ingredients even spill over into the Post-Contact menu, with dishes such as blue cornmeal–crusted onion rings or salad with fried chicken (also coated in blue cornmeal) and shaved jícama.

The menu enacts a collision of the two periods with curios such as fry-bread—reminiscent of the Pueblo Indians' fat-fried solution to government rations in the 1800s—or fried Kool-Aid pickles, a creative comfort food among the Pueblo.

What ingredients the restaurant doesn't source from local tribes are pulled from the IPCC's Resilience Garden, a fertile lot where elders teach younger Pueblo generations how to grow endangered crops using traditional farming techniques. The garden is visible from the restaurant's outdoor patio, which also offers unobstructed views of sprawling plains that open up onto the Sandia Mountains, the sacred centerpiece of an ancient, resilient people.

Related Tags

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

September 23, 2021